Timothy Nunan

Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies

Follow on Twitter @timothynunan

How did Afghanistan in 2016 end up, yet again, as the graveyard of empires? Not only do Taliban franchises control much of the countryside outside of Kabul, but the start-up Islamic State battles them for influence. Tens of billion of dollars of aid have gone missing. Many Afghans are voting with their feet, forming one of the largest refugee diasporas in the world (a title they held until the Syrian Civil War).

Yet as my recent book, Humanitarian Invasion: Global Development in Cold War Afghanistan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016) shows, tortured attempts to develop Afghanistan have a long history. Sure, events like the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842) have left a deep imprint on how outsiders view the place. But for much of the twentieth century, neutral Afghanistan wasn’t at war with any of the superpowers. And when the Soviets went into Afghanistan, they did not annex it into some “Soviet empire.” The Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was a dues-paying member of the U.N. General Assembly, and Kabul played host to international conferences touting the regime’s solidarity with the Third World.

Viewed from this perspective, Afghanistan looks less like a “graveyard of empires” and more like a graveyard of the Third World nation-state, both in its developmental iteration and its left-wing socialist version of the 1970s and early 1980s. Understanding Afghanistan as a place weakly integrated into the international state system explains why so many foreign actors flocked there in the name of development. It also explains the journey from the Afghanistan of the 1960s, which had the highest level of per-capita development aid anywhere in the world, to the Afghanistan of the 1980s, when Peshawar (in neighboring Pakistan) hosted more NGOs than anywhere else in the world.

Let us embark, then, on a multi-decade tour of Afghanistan as it became entangled with successive regimes of high developmentalism, real existing socialism, and transnational humanitarianism in a world defined by the Cold War.

Developing Afghanistan

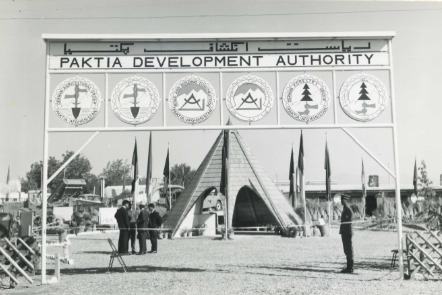

Our journey begins in the valleys of what are today Paktia and Khost Provinces in eastern Afghanistan. People might think of these lands today as dry badlands, and today, they are. But for much of the twentieth century and times before that, they were known for their prized Himalayan cedar. The wood fetched high prices in the markets of Karachi, Pakistan.

During the 1960s, however, Paktia hosted one of several developmental interventions into the Afghan countryside as Moscow, Washington, and others courted neutral Kabul. West German foresters sought to help the monarchy re-orient Paktia’s cedar exports toward Kabul, not Karachi. Germany had a long history of aiding Afghanistan, and as Afghan technocrats told their German interlocutors, managing the forest economy of Paktia was essential if “wild” tribesmen were not to stage a “hunger march” toward Kabul and overthrow the government.

Yet German efforts revealed the problems with creating developmental nation-states. West German loggers trained locals in “sustainable” logging techniques, so that the forests could be preserved. But fly-overs of the woods showed how much they continued to shrink as wood flowed across the border.

But by the early 1970s, foresters glumly noted that many of the woods had entered a state of irrecoverable decline, depriving many men of their livelihood and sparking inter-tribal feuds over who owned which forests. Many of the foresters conceded that the entire idea of directing Paktia’s wood exports to markets in inland Kabul, and not the far larger market of Karachi, had been misguided from the start. Wood simply kept leaving the Afghan “national economy,” with no taxes and no customs revenue from it.

The foibles in Paktia themselves reflected the breakdown of developmental statehood. By the mid-1960s, not only the Americans but also the Soviets were reconsidering what it would mean to develop every single country in the world. And as places like Paktia made clear, ex-colonial borders rarely corresponded to the natural markets for commodities like cedar, much less the “national economies” of this or that independent state. Little wonder that by the mid-1970s, many in the Third World critiqued the gap between political sovereignty and economic self-determination.

But there was another game in town for many nationalist intellectuals in the buyer’s market of ideologies that would ensure their new nation’s place in the sun. When the Americans refused to provide Afghanistan membership in the anti-Communist Baghdad Pact in 1955, Afghan leaders turned to the Warsaw Pact for military training. When many of these Afghans went to the Soviet Union to receive military training, their experience was not disillusionment but social advancement.

These army officers eventually united with Communist intellectuals like Karmal and took power in Afghanistan in April 1978. They soon drove the country into near-civil war, so the Soviets felt compelled to stabilize the situation. Over Christmas 1979, the Soviet 40th Army invaded the country.

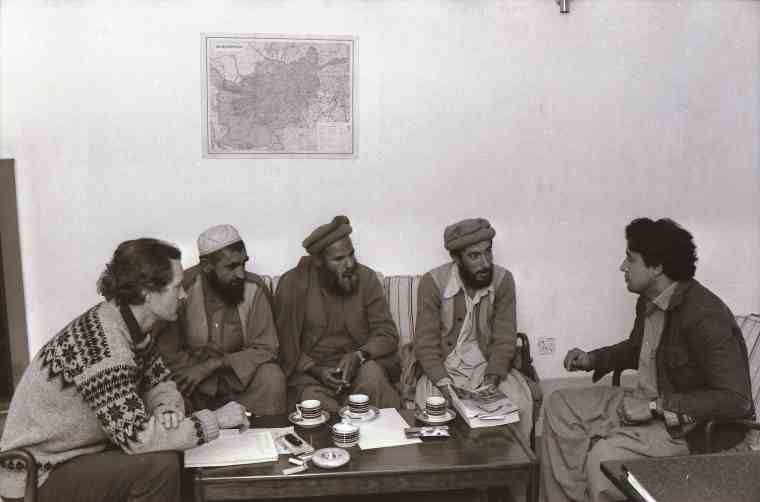

Much has been written on the Soviets’ decision-making process to enter Afghanistan, but what Humanitarian Invasion brings to the table is a focus on the experience of Soviet advisors to the young Afghan socialist republic. Gaining access to archival documents produced on the ground throughout the 1980s, I’ve reconstructed the Soviets’ and Afghans’ efforts to build “real existing socialism” in a country that had officially only recently transitioned out of feudalism.

The more I read these files and interviewed former advisers, the more I saw the Soviet vision for the Third World coming apart. The entire premise of the Soviet model that these men were importing to places like Paktia was based on the idea of factory floors and trade unions as the building blocks of society.

But within Afghanistan, there were very few of these industrial institutions anywhere to be found. Most of the large Soviet-built enterprises were either in Kabul itself or the Soviet-built petroleum infrastructure in the north. But the entire Fordist material base meant to sustain mass politics was absent. And the Soviet and Afghan Armies struggled to maintain security across enough of the countryside for schools, workers’ clubs, and “organizations of working housewives” to thrive.

In short, the Soviet vision for Third World nation-states like Afghanistan unraveled on its own terms. But what made the Afghan case especially telling of shifts in global debates about sovereignty was the fact that it saw left-wing European activists support the breach of Third World national sovereignty in a way that would have been unthinkable a mere decade before. Using the archives of the two largest NGOs to operate in occupied Afghanistan—France’s Médecins sans Frontières and the Sweden-based Swedish Committee for Afghanistan—Humanitarian Invasion examines this turn.

Both groups, it bears stressing, had anti-colonial or left-wing roots. When Saigon fell on April 30, 1975, many such activists rejoiced. Yet as the North Vietnamese Communist government took power, the South China Sea soon filled with an armada of makeshift dinghies, full of people seeking to escape the rule of the Third World socialist state. Images of strangers drowning spurred activists to action. By the end of the 1970s, humanitarian entrepreneurs supported intervention into Third World socialist states where they had defended Third World sovereignty before.

Much of the second half of Humanitarian Invasion explores the drama that ensued as humanitarian actors–in alliance with Islamist militias–challenged the Soviets on the ground in occupied Afghanistan. Improbably, by the 1980s Afghanistan had the battleground for two different left-wing visions of Third World sovereignty: one, the Soviets’ vision of Third World sovereignty plus socialist intervention; the other, a humanitarian ethics of interdependence that embraced humanitarian intervention to save not socialism, but human lives.

Laying to Rest the “Graveyard of Empires” Myth

What are the payoffs of viewing the histories of Afghanistan and the actors connected with it in the way I have outlined above? For one, tracking Afghanistan’s foreign engagements allows us to escape what historian Nile Green calls the “analytical dichotomy” that rules much writing about the country. Typically, explains Green, scholars view Afghanistan’s twentieth century through the axial moments of 1929 (a coup d’état that ended two decades of Afghan nation-building efforts) and 1979 (the Soviet invasion).

But this narrative reifies a tendentiously nationalistic vision of Afghan histories, in which Afghans make the nation, and foreigners destroy it. Humanitarian Invasion fills in this “missing middle” of the mid-twentieth century, examining how Afghans and foreigners interacted with one another. It sees Afghan history as an integrated whole, rather than a collection of images—1842, 1929, 1989—that contribute to the “graveyard of empires” mythology.

What if you aren’t particularly interested in the history of Afghanistan, or even the major actors who transformed it during the Cold War? In Humanitarian Invasion I respond to probing critiques of global history raised by critics who warn about merely showing connectedness for connectedness’ sake.

Afghanistan has always been connected with global processes, but what Humanitarian Invasion brings to the conversation is an awareness of how Afghanistan’s Cold War entanglements reflected bigger debates about Third World sovereignty. Perhaps it is not too late to bury the “graveyard of empires” narrative—if also the hopes for the latest developmental intervention to touch down in Kabul.

wonderful post

Afghanistan was NOT the grave yard of the British Empire. Yes, it did slaughter a large number of British soldiers and drive the British out of Afghanistan. Russia was driven out by its own over extension and economic debacle caused by Totalitarianism coupled with US leveraging Pakistan and the rest of the Sunni axis as its “boots on the ground” But the US debacle in Afghanistan was by design. Tweedle Bush and Tweedle Blair deliberately took the war away from Afghanistan to deflect anger over 9/11 from the real perpetrators (Saudi Araba and Pakistan) to Iraq. The reasons? (1) The US-NATO-Sunni axis forged by Nixon, Kissinger and Sheikh Yamani. (2) Al Shebab like Boko Haram, Daesh, Pakistan Army, Jaish e Mohammed, Laskar e Taiba, Turkish Army, Saudi Army and so on are different regiments of Taliban (students of the Quran and the Hadiths raised in Madrassas around the world funded by Saudi and other Sunni Petro Dollars to impose what they have learned, Islam, on the rubble of civilization). They are not merely US allies, but US’ “boots on the ground” that are bringing democracy (regime change and chaos) on America’s behalf along with Islam (vandalism, gang rapes, beheadings, genocides, slavery and so on) on Mahomet’s behalf to the world.

US Greed and Islam’s hate made the perfect consort dancing together since Nixon, Kissinger and Sheikh Yamani forged the US-NATO-Sunni axis. The Islam Mahomet created was born from his selling his soul to Satan to sate his hatred with revenge on Muqqa. The US became partners in crime as it submitted to the oil well betwixt the mammoth thighs of Mammon.

US actions have been the deliberate advancement of a consistent pro-Sunni Islamic Policy since Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger and Sheikh Yamani forged the US-NATO-Sunni Petro Dollar Axis that led, among other things, to sending the Seventh Fleet up the Bay of Bengal to defend Pakistan;s right to practice Islam (mass rapes, sex slavery, genocide, vandalism etc) in 1971 and Turkey’s annexation of half of Cyprus in 1973 and the persecution of Shia Iran in International affairs. The US is a Polyphemus being ridden by Sunni (Petro Dollar) Islam as Sindbad was by the “Old Man of the Sea”. The White Hice, the State Department and the CIA are not accountable to the US people as much as internal US governance. From Nixon’s China and Pakistan to “contain India” (a suicidal India that is its own worst enemy, standing as a Totalitarian Anti-Hindu State on the two fundamental pillars of “reservations” and “corruption”) as State Policy, Bush (the Father’s) CIA when he founded the Bush wealth from largesse found under the Tent of Saud, to Reagan’s Iran-Contra and Taliban, to Clinton (the husband’s) bombing of Belgrade to cede Islam its first ethnically cleansed enclaves (Bosnia and Kosovo) in Europe since 1489, to Bush (the Son’s) Iraq and Obama (The Holy Ghost’s) ISIS, the White Hice have been acting just as any mercenary on the pay roll of Sunni (Petro Dollar) Islam might. Pakistan is the US’s consistent cat’s paw to contain India since Nixon as it has been China’s since inception. Islamic Terror is Pakistan’s favoured and consistent weapon in dealing with India and has full White Hice blessings. The US has tossed one country after another into the maws of Sunni Islam. Afghanistan, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Cyprus, Tunisia, “The Arab Spring” and Libya. Now the US has thrown its NATO allies in Europe into the anti-civilization and dehumanizing chaos called Islam.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.