From the Getty going free, to card games introducing French children to colonial management, to First World War body armor. Here are the week’s top picks in imperial and global history.

*In case you missed it, the Getty Research Institute has now made millions and millions of photos free. That’s right, free. And be sure to also check out some amazing exhibits on imperial and global history. In their current exhibit, “Connecting Seas: A Visual History of Discoveries and Encounters,” for example, they have a French children’s game that helps them learn the basics of colonial management:

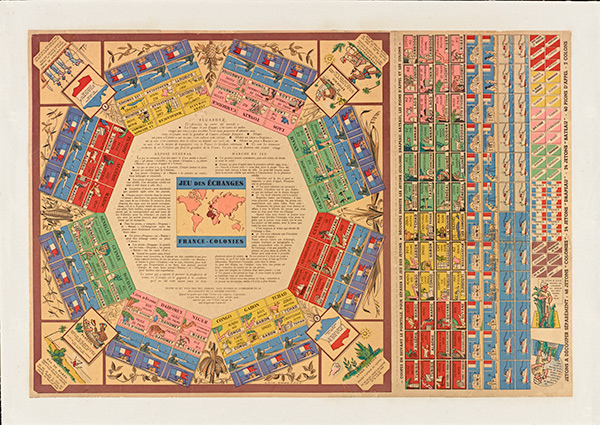

One of the most vivid renditions is this jeu des échanges, or “trading game.”

Made in France at the outbreak of World War II, the game sought to educate children about the colonial world supporting the French economy. With tokens printed in vivid colors to represent places and natural resources in regions colonized by the French, from North Africa to Oceania to southeast Asia, this game encapsulated the mighty business opportunities that lay ahead for adventurous explorers willing to embark for faraway colonial lands.

As described in the rules at the center of the board, the underlying purpose of the game was to admire, through play, the greatness of the French colonial undertaking. The colonization of a land was symbolically achieved first by hoisting the French flag on its soil, then by the establishment of a hospital, a school, and ultimately a harbor. But the ultimate win was to export the rich natural resources of the colonies back to France by boat. Images on the game provide a vivid picture of the vast variety of resources, including animals, plants, and minerals, that the colonies provided to France from all around the globe.

*Or how about some depictions of an Aztec ceremonial precinct in Tenochtitlan just after the Spanish conquest?

*Over at the Junto, all you historians of early American history will no doubt be glad to see that March Madness is back, with nominations starting next week:

We ask our readers to nominate books about early American history, then we pair them off against each other, until there’s only one book left standing. Last year’s tournament can be found here: Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom ultimately proved victorious. This year, we’re going to be doing the same thing, only with a twist: entrants to the tournament will be limited to books published since 2000. Last time around, we noticed a tendency to reward older, more established books. We wanted to bring the same liveliness of discussion to more recent works, and to highlight recent work that deserves the prominence of old favorites.

*Finally, our friends at itshistorypodcasts.com have another fascinating piece, this one on the invention of a new body armor during the First World War that nevertheless failed to catch on. Perhaps it wasn’t stylish enough? The body armor was named after its inventor Dr. Guy Brewster, and was ‘developed by the United States Army towards the end of the war. Whilst it was very clumsy and heavy it could withstand the bullets from a Lewis Gun. Its problems occurred due to maneuverability being massively reduced and the small issue of the helmet not turning’, making visibility nearly impossible.

This didn’t stop Dr. Brewster from excitedly telling America of his invention. But being a man of both action and science, Dr. Brewster didn’t just tell people about his invention, he demonstrated it. The picture below is of Dr. Brewster in his armor; the accompanying article describes how the American military tested his armor by shooting at the suit while Dr. Brewster was inside it. You would think that one or two shots would be sufficient to prove the protective qualities of the armor, but that was not the case for the American military. Its soldiers unleashed a ‘rain of bullets’ at the good Doctor. Apparently the military top bods were very pleased as no bullets penetrated the armor’s thick hide. I can only imagine that Dr. Brewster was very pleased about this too. At the end of the experiment Dr Brewster declared that being shot by a machine gun while wearing his armor was only about ‘one tenth the shock which he experienced when struck by a sledge-hammer.’ One has to wonder how he knew what it felt like to be hit by a sledgehammer.

Great post Marc I’ll have to check out Getty How about this for a post-colonial conundrum: why, given they were produced in their tens of thousands, and are said to have been hung on the walls of every school classroom, can one no longer find any of those large maps of the Victorian and Edwardian empire? Best Andy

Sent from my iPad

I admit that I am stumped–and quite curious as to the reason why. Any possible guesses/answers?

Anything that is in the vicinity of kids stands a poor rate of survival. Most of “the red bits on the map” were probably ketchup!

Appreciating the hard work you put into your site and detailed information you offer.

It’s good to come across a blog every once in a while that

isn’t the same old rehashed material. Excellent read!

I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.