Giuseppe Paparella

University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @giuspaparella

Debates over the post-Second World War origins of Sino-American relations continue to inform – and daunt — policymakers and foreign policy experts in their effort to figure out a viable strategy to deal with Beijing. Writing in Foreign Affairs in 2018, Kurt M. Campbell and Ely Ratner – Biden’s National Security Council Indo-Pacific Affairs Coordinator and Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs respectively – branded the Truman Administrations’ various efforts to shape China’s behaviour as a failure. However, in commenting on the article James Curran – an Australian scholar on U.S. foreign policy – noticed that both this piece and the several respondents to it collectively failed “to acknowledge … the pervasive influence of American nationalist mythology on U.S.-China policy over the last seventy years.” In conclusion, Curran noted that “a critical but to date sadly neglected part of that process must surely involve taking a good, hard look at how the myths of American nationalism have influenced the course of U.S.-China policy since 1949.”

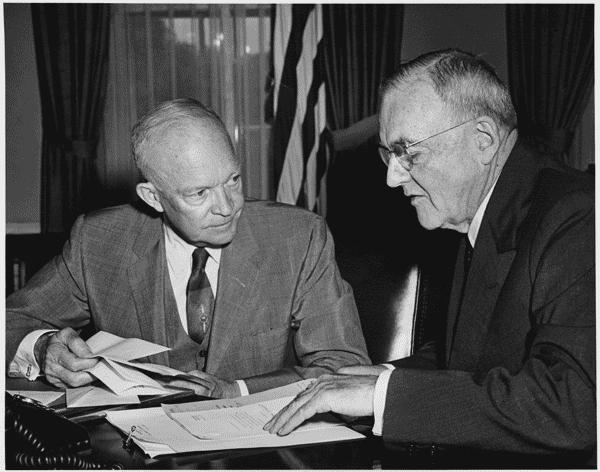

My newly published open-access article in The International History Review takes a fresh perspective and contributes to these debates. In it, I argue that between late 1948 and early 1949 Communist China and the United States might have been able to strike a more collaborative relationship had Truman applied more restraint to his nationalist colony image of China – a concept developed in-depth in the article – and been more willing to listen to Dean Acheson and advisors in the Division of Chinese Affairs, who promoted the “Chinese Titoism” strategy.

Continue reading “Losing China: Revisiting American Involvement in China in the Early Cold War“

You must be logged in to post a comment.