Marc-William Palen and Richard Toye

University of Exeter

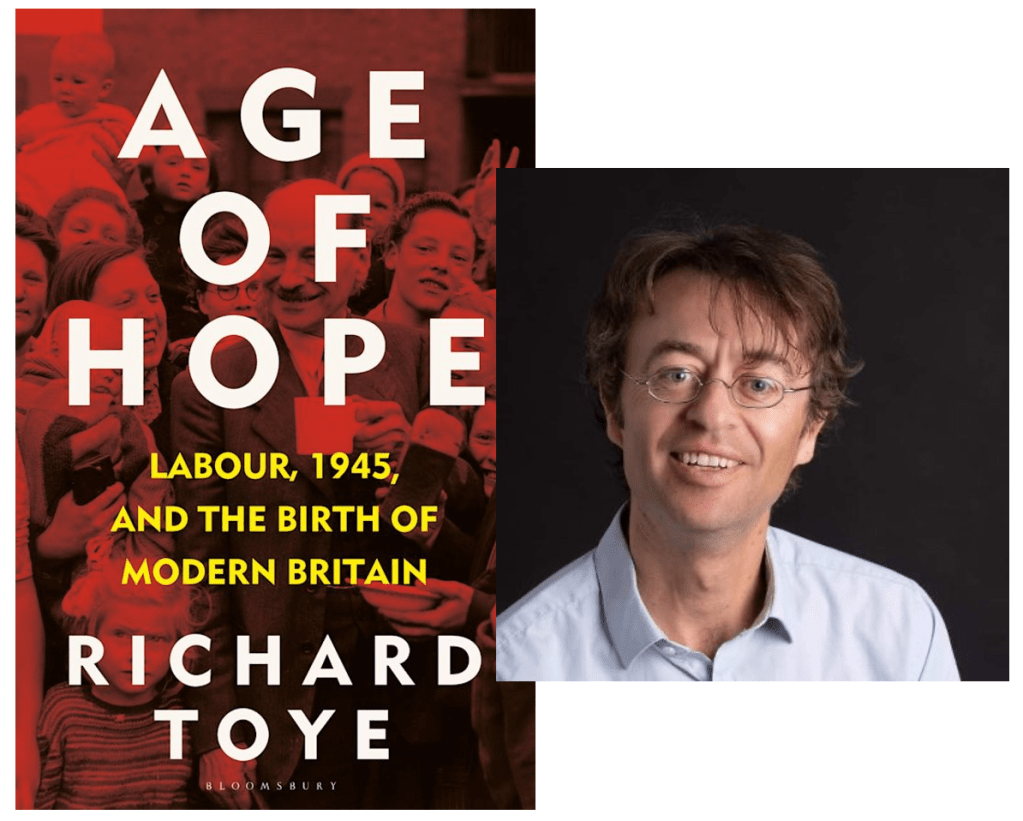

Richard Toye, Professor of Modern History at the University of Exeter, needs little introduction to readers of the Imperial & Global Forum. Toye is a leading historian of modern British politics, the British Empire, and postwar internationalism. Among his previous publications are The Labour Party and the Planned Economy, 1931-1951 (2003), Churchill’s Empire (2010), Arguing about Empire: Imperial Rhetoric in Britain and France, 1882-1956 (with Martin Thomas, 2017), Winston Churchill: A Life in the News (2020), and, with David Thackeray, Age of Promises: Electoral Pledges in Twentieth Century Britain (2021). Toye is also former director of the Centre for Imperial and Global History and the host of the Imperial & Global Forum’s ‘Talking Empire’ podcast series. You can follow him on Twitter/X @RichardToye and on Threads @Richard_John_Toye. His newest publication, Age of Hope: Labour, 1945, and the Birth of Modern Britain, will be published with Bloomsbury on 12 October 2023, in advance of the 100th anniversary of the first Labour government in 2024. Age of Hope is the subject of our interview today.

MP: Briefly, how would you summarize Age of Hope?

RT: It is an attempt to put the Labour government of 1945 into long-term perspective. This involves both going back to the 1880s, when many of its leading figures were born, and forward to the present day, when its legacy continues to be felt. Although I hope that readers of all political persuasions can profit from it, I don’t attempt to be absolutely politically neutral. Especially in the conclusion I make some suggestions about how the Labour Party might learns some of the lessons of the Attlee era as it stands (probably) on the edge of power.

MP: What do you consider to be the book’s most important takeaway(s) regarding the history of the Labour Party and the Attlee Government’s legacy?

RT: It is a commonplace that, when Labour took over, the UK was on the edge of bankruptcy and that the years that followed were ones of many privations as well as ones of reform. What hit me especially hard when looking at all the evidence anew is exactly how frightening and depressing it was that, almost as soon as WWII had finished, a new war with the Soviet Union started to look like a real possibility. Retrospectively we think of this as “the start of the Cold War”, knowing that it didn’t turn into something worse. But at the time, of course, it was experienced as a form of constant anxiety (though doubtless some of the population just ignored it all). So there is irony in the title Age of Hope, as it was either a very short age, or at least one where the edge was taken off the hope remarkably quickly. I also think, in the light of the Ukraine war today, we should turn the question round and not ask “Who was to blame for starting the Cold War?” but rather “Who should get the credit for the fact that it didn’t turn into something worse?” And I think the answer is that some of it should be divided between the USA, the UK, and the USSR, though doubtless not in equal measure.

MP: One of the challenges that historians invariably face is making sense of historical complexities without making their analysis overly complicated. You ably accomplish this feat here. And yet when it comes to the Labour Party, this is no easy task. You yourself describe the party as ‘both visionary and pedantically pragmatic, genuinely internationalist and subject to Cold War paranoia, socially radical in some respects, petit bourgeois and conventional in others’ (15). What was your strategy for making Labour’s complexities easy to digest for your readers?

RT: You are very kind, but the truth is that I have probably ended up eliding some of the complexities. If the book is easy to digest, it is probably because I didn’t feel the need to give an encyclopedic treatment, or to give every theme or episode a regulation-type amount of space. This was possible in part because previous generations of historians did a really good job of uncovering and telling the basic story thoroughly on the basis of the documents that (largely) became available for study in the 1970s and 1980s. For example, the late Alan Bullock wrote a massive, three volume biography of Ernest Bevin. Now, it is certainly possible to uncover documents that Bullock didn’t know about, but on the basis of what he had at hand he did an amazing job of tracing the details of the many controversies in which he was involved. So when I came to write about Bevin, I didn’t want to redo what Bullock did, but rather to select key moments and use them to illustrate the bigger picture.

MP: While this is a book about the Attlee Government, you first take the reader on a sweeping tour that teases out the evolution of the Labour Party from its late-19th-century origins, to the first Labour Government in 1924, to the Second World War. How did you decide on when to begin your story? Or put another way, why do we need to know the origins of the Labour Party to properly understand the Attlee government and its legacy?

RT: I should give credit to Robin Baird-Smith, my editor at Bloomsbury, for the excellent suggestion that 1924 should be included. I took his idea and ran with it, thinking that you actually need to go back even further. Thinking about Attlee, Bevin, Dalton, Morrison and Cripps all having formative experiences at the end of the Nineteenth Century made me get on my hobby horse about how the Victorians are misunderstood. Yes, of course, there was a strong stuffy, boring, conventional element in that society, but it was also a time of intellectual experimentation and utopianism. Socialists looked at the amazing economic developments of the time and were impressed by them but also saw gross inequality – “Poverty in the midst of plenty.” If you look at the 1940s reforms you see both a Victorian belief in Progress (and an assumption that the nation’s wealth would continue to grow) alongside a conviction that economic forces needed to be controlled, channeled, and redirected in the interests of social harmony,

MP: As you outline in the book, the Labour Party changed its position on a wide array of foreign policy issues from its late-19th-century origins to the Attlee Government. But you also contend that there was some continuity. In particular, you state that Attlee and his foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin (1945-1951), carried forward ‘a long-standing Labour patriotic-cum-internationalist tradition that has encompassed almost all of the party’s leaders and Foreign Secretaries’ (99). Could you briefly unpack this element of continuity?

RT: Briefly? Oh, gosh. Well, I would say that, even at times when the party was advocating radical foreign policy positions such as unilateral nuclear disarmament, some kind of Radical variant of patriotism/British exceptionalism was present. It was “If we disarm we will give a moral example and we will lead the world”, not “We’re now a third-rate power and nobody else cares if we have nuclear weapons or not, we might as well save the money.” To bring in Bevin, he famously attacked the party’s then leader, George Lansbury, at the party’s 1935 conference which took place at the time of the Abyssinian crisis. Lansbury (though a patriot too) was a pacifist, which certainly made him an outlier amongst Labour leaders. He was forced to resign and Attlee, his deputy, took over the leadership. And kept it for twenty years. So his success was very much predicated on the party’s adoption of Bevin-style pragmatism.

MP: Age of Hope casts a wide net over the Attlee Government’s foreign policy surrounding the early Cold War and decolonization, particularly with respect to the USA, the USSR, nuclear weapons, Palestine, and India. Despite Bevin’s self-professed claim to, as you put it, ‘avoid secret diplomacy’ (96), many question marks yet remain surrounding the Labour government’s foreign policy, as do numerous myths surrounding its commitment to anti-colonialism. What question mark or myth pertaining to the Attlee Government’s foreign policy would you rank ‘highest priority’ for future scholarship?

RT: There is still quite a lot we’re still not allowed to know, especially about the activities of the Security Services (more so MI6 than MI5). I found a number of closed items in the papers at the National Archives and put in a lot of FoI requests. Some of them were granted, and the material was not especially interesting, frankly. Others were turned down – on, for example, the grounds that they might damage relations with foreign powers. Maybe that material isn’t interesting either, and the officials are just overly cautious. Or maybe there’s something really there! The problem is, you don’t know what you don’t know. I guess I would say to other scholars: if you come across a closed item, don’t just move on, but take the five minutes needed to request that the authorities open it. You never know your luck.

MP: As things stand, a new Labour Government, with Keir Starmer at the helm, seems inevitable following the next general election. In the meantime, the British press and Starmer himself continue to cultivate the idea that he is ‘emulating Attlee’ (236). What do you make of these comparisons between Starmer and Attlee?

RT: On the one hand I think they are a bit of a stretch, on the other, I don’t see them as inherently ludicrous. The comparison makes more sense when you realise that Attlee was not always the left-wing paragon that some people would have us believe. Starmer has said that Jeremy Corbyn will not be allowed to stand as a Labour candidate. On Attlee’s watch, both Stafford Cripps and Aneurin Bevan were expelled from the party (though they were both subsequently let back in). On a positive note, I would say that any leader of any party could learn from Attlee’s close knowledge of his Members of Parliament and their interests and habits. If you need someone to do something, it is good to be able tell your assistants that the MP in question is, at that particular hour, to be found in the Commons tearoom eating a kipper. This rule may apply even in the era of the smartphone.

Age of Hope: Labour, 1945, and the Birth of Modern Britain is now available for purchase at Bloomsbury (Hardback £25.00, Ebook £17.50)

You must be logged in to post a comment.