http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/8001379546/urn-3:FHCL:37108245/catalog

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From the deadly African legacy of the US War on Terror to the Northampton shoemaker who caught the Auschwitz commander, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history.

In Africa, the Legacy of the US War on Terror Is Death and Chaos

Nick Turse

Jacobin

America’s global “war on terror” has seen its share of stalemates, disasters, and outright defeats. During twenty-plus years of armed interventions, the United States has watched its efforts implode in spectacular fashion, from Iraq in 2014 to Afghanistan in 2021. The greatest failure of its “forever wars,” however, may not be in the Middle East, but in Africa.

“Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated,” President George W. Bush told the American people in the immediate wake of the 9/11 attacks, noting specifically that such militants had designs on “vast regions” of Africa. [continue reading]

Kettle of Vultures

Jamie Martin

London Review of Books

The earliest known interest-bearing debt is recorded on a 4500-year-old clay cone from southern Iraq. Its cuneiform inscription narrates a border dispute between two ancient Sumerian cities, Umma and Lagash, over control of a fertile plain and a debt in barley that the former owed to the latter. Unable to repay the debt, which had grown to astronomical proportions, Umma’s ruler attacked Lagash but was killed as he fled the scene of battle. The clay cone is a memorial to his defeat, one of several remarkable artefacts produced by the long-running conflict between the two cities. Another relic features one of the oldest surviving visual representations of warfare: a phalanx of spear and shield-wielding Lagash soldiers in formation, a kettle of vultures carrying off the heads and limbs of their slain enemies, a naked priest pouring libations over a pile of corpses, and a sacrificial bull tied on its back to the ground.

It’s striking that the earliest narratives of unmanageable debt and organised human violence coincide. The societies of ancient Mesopotamia developed numerous types of credit – to finance long-distance trade, for example, or to help struggling farmers – as well as instruments of coercion to enforce the claims of lenders. Some of these involved the pledging of oneself or one’s family as security; there were also occasional amnesties for those trapped by unsustainable obligations. The Code of Hammurabi, composed around 1750 bce, contained extensive rules about borrowing, including a limit on for how long – three years – a debtor could enslave himself in lieu of repayment. [continue reading]

Irish woman inspired to return African and Aboriginal antiquities by Guardian article

Dalya Alberge

Guardian

An Irish woman has been inspired by the Guardian to return her late father’s collection of 19th-century African and Aboriginal objects to their countries of origin. Isabella Walsh, 39, from Limerick, has contacted embassies and consulates in Dublin and London to repatriate 10 objects, including spears, harpoon heads and a shield, after she read about other cases in the newspaper.

The objects had belonged to her father, Larry Walsh, an archaeologist and curator of the Limerick Museum, who had always cherished them due to his passionate interest in African and Aboriginal cultures. But he also believed that such objects belonged to the peoples from whom they had originated. [continue reading]

Settler Colonialism

Lachlan McNamee

Aeon

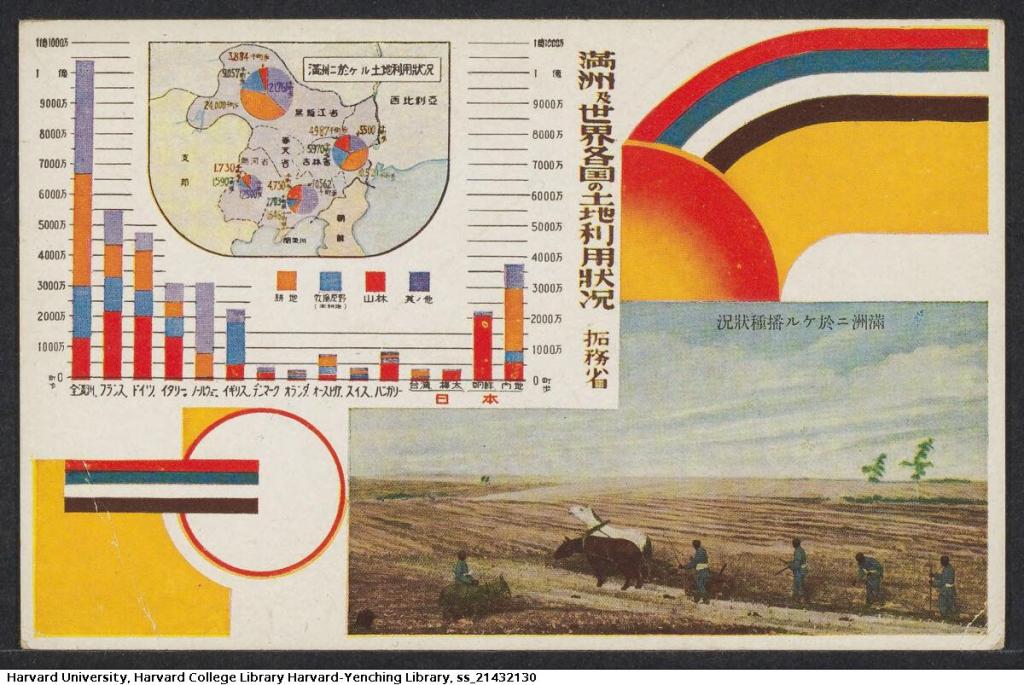

In 1931, Japan invaded northeast China and established a client state called Manchukuo (Manchuria). To secure control over Manchuria, over the next 14 years, the Japanese government lured 270,000 settlers there by offering free land to ordinary Japanese households. Japanese propaganda stressed, importantly, that this colonisation scheme was not inconsistent with Japan’s commitment to racial equality. Japanese farmers would bring new agricultural techniques to Manchuria and ‘improve’ the lives of native Manchus, Mongols and Chinese by way of example.

Japan’s settlement of Manchuria represents a case of settler colonialism, a concept that was initially developed in the humanities to explain the violent history of nation-building in North America and Australasia. Unlike traditional colonies such as India or Nigeria, as Patrick Wolfe explained, settler colonies do not exploit native populations but instead seek to replace them. The key resource in settler colonies is land. Where Indigenous land is more valuable than Indigenous labour – often because Indigenous peoples are mobile and cannot be easily taxed – native peoples are killed, displaced or forcibly assimilated by settlers who want their land for farming. Settlers and their descendants then justify these land grabs through discourses that both naturalise the disappearance of Indigenous peoples (it was disease!) and stress the benefits of the civilisation the settlers brought with them. [continue reading]

The Northampton shoemaker who caught the Auschwitz commander

Helen Burchell

BBC News

Victor Cross worked in the family business – the British Chrome Tanning Company – in Northampton, before the war. He travelled widely, purchasing hides for the high-quality women’s shoes the company made. His father sent him to Germany to learn more about the trade, and Victor became fluent in the language while there.

When World War Two broke out in 1939, he joined the British Army, later moving to the Intelligence Corps, which was keen to recruit German speakers. At the end of the war, Capt Cross was sent to Germany in command of 92 and 95 Field Security Sections and, with others, was tasked with capturing escaped Nazis. Among the thousands of names on a list given to them was Rudolf Höss – sometimes referred to as Hoess. Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss had joined the Nazi Party in the early 1920s and later became an SS officer, working at a concentration camp at Dachau, before transferring to Auschwitz, which he ran until 1943. [continue reading]

You must be logged in to post a comment.