By Ikuo Harimoto, Marian Gabani Gimenez, Dongfang Liu, Javiera Scarratt, and Alexander Van Herpe

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven; Richard Toye, University of Exeter; Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Independent researcher; Luca Pes, Venice International University; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

When we were assigned the Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, in the neighborhood of Castello, as the central point of our fieldwork for the 2024 “Linguistic Landscapes” Summer Course at Venice International University, we had to decide on the criteria to delimit the area we would be exploring. Based on Kevin Lynch’s (1960) typology of the contents of the city image, i.e. referable physical forms that people recognize and rely on in their wanderings through the urban space, we reflected on the various possible maps that Venice offered. As pointed out by Lynch, the image of the same physical reality shifts according to the circumstances of viewing, and Venice is the locus where numerous circumstances coexist: for instance, the canals seem to work as an edge for earth-bound wanderers, but a path for water-bound locals. In this reflection, we realized that water could be seen as this ambiguous–or fruitful–element according to which the “circumstances of viewing” shift profoundly. We opted, thus, to define the canals as the limit for our explorations.

Venice is formed by several small islands, connected by canals, lagoons, and waterways. One could argue that this is what makes Venice distinctively attractive to people all over the world. Such geographical features, coupled with its unique history, foreground a particular identity, expressed in signs, art, images, and structures across the city. On the flip side, Venice’s geography and history also bring their own issues: over-tourism, rise in water levels, and sinking foundations. This tension is what intrigued us and guided this project. Starting from the Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, a 14th-century church of Gothic architecture, we wandered through the paths and followed the margins of the canals seeking structures, signs, and images that referred to water, however loose the reference might be. Our goal was to understand if and how water informed and still informs the architectural, semiotic, and linguistic landscape of Venice.

We divided the results of our research into three topics: the uses of water (utility), protection from water-related events (defense), and water as a cultural element. The first topic explores the structures in place to make use of water in Venice and how they differ depending on who is making use of it. The second topic investigates the remnants and the new strategies to defend the land from water-related events and disasters. In the third and last topic, we argue that water is also present as a symbol in the cultural landscape of Venice.

The landscape between the utilitarian and the decorative

The semiotic landscape of Venice is permeated by structures and signs that emerge as testimonies of the different uses of water in the city. While this is not exclusive to Venice, we will see that the centrality of water in the settlement and development of the island is reflected in the cultural and structural elements of the Venitian landscape. Moreover, the diversity of experiences of the city is visible by the placement of these elements. In Psarra’s words, “Venice appears different to the waterborne passenger than to the pedestrian” (2018, p. 232).

The logistics and practicalities of being water-bound are apparent in the landscape, although they can be overlooked or understood differently by earthbound pedestrians. For example, mooring hoops can be found abundantly on the sidewalks (Images A and B), but their utilitarian character is more evident to individuals who move around Venice through water. For pedestrians, the hoops become a less utilitarian element, although equally present as an integral part of the city’s landscape. In this case, the landscape remains the same for both water and earthbound individuals. The differences lie in the meaning of the elements present in the landscape. One could also argue that the difference in meaning implies in a difference of attention paid to given elements, as well as of their relevance in daily activities.

Images A and B

In other cases, the landscape varies depending on the individual’s location. Some signs are only visible from the canals, by water-bound observers (Image C). During our research, those were the most difficult signs to register, since they tend to be obscured from the pedestrian gaze, not intentionally so, naturally, but due its utilitarian nature. (Image D)

Images C and D

On the other hand, other signs which are directed at water-bound individuals are hypervisible, standing out from the lagoon and canals alike. (Image E) The bricole, panile, and dame are everywhere in the aquatic sections of the Venetian landscape, but they communicate solely with water-bound individuals who are literate in this language. (Image F) The earthbound pedestrian, especially the eventual visitor and tourist, remains oblivious to the message transmitted by those structures.

Images E and F

Finally, there are other structures that permeate the Venetian landscape and point to a different use of water. Instead of pathways for locomotion and movement, in the following cases water is a resource for survival and defense. The antincendio (fire suppression) system can be easily overlooked by passersby, which once again speaks to how meaning is accentuated or attenuated by contextual cues. (Images G and H) As a utilitarian structure, the bright red color is intentionally chosen to make the system hypervisible in case of need, but it easily becomes part of the landscape in ordinary daily life.

Images G and H

(Image I) Another example of how meaning is context-dependent, and how the landscape is experienced differently by individuals, are the communal cisterns, once important to the collection of pluvial water, and now exclusively decor items, whose role in shaping the historical and cultural landscape we will further explore later. (Image J) However, even as a utilitarian structure, the lions that adorn the wells point to their multi-layered signification in the landscape–and, naturally, to the artificiality of the categories we propose here. Moreover, the lion imagery creates an intertextual continuum with more contemporary structures that offer potable water to pedestrians. (Image K)

Images I, J, and K

On water and against it

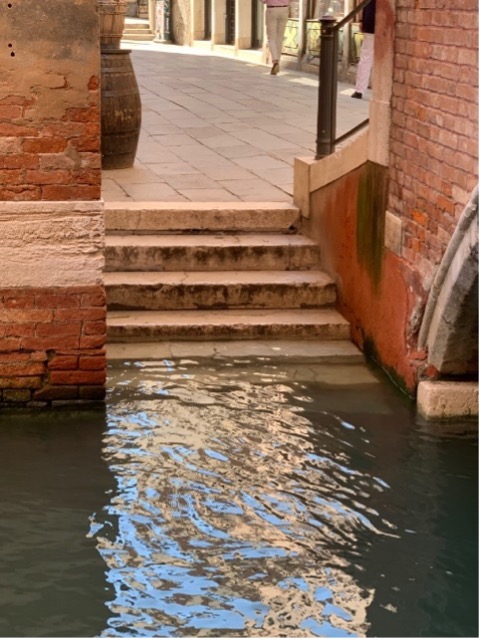

Apart from the daily life utility aspects of water, due to the peculiar geographical and historical background of Venice as an important trading city, the city also needs to be protected against the water. Venice consists of 188 small islands and all the houses are built on piles of swampy soil, which makes it less solid than buildings on the mainland. In addition, during the 20th century, Venice was pumping out groundwater under the city for chemical industry. Due to the caused erosion, according to the account of Zanchettin et al (2020), there has been a gradual lowering of the surface and a significant rise of the water level, which causes the city to sink (1-2 mm a year) in their estimation. Nowadays in the streets of Venice one can find a lot of visual markers of this evolution, like stairs and windows that used to be above the water but which are now flooded (pictures – SET 1). On top of that, the daily passage of (motor)boats as a means of transportation or tourist attraction throughout the city causes higher waves which lead to even more damage.

Picture Set 1

The water in and around Venice mainly comes from water currents of the Alpine rivers and the Adriatic Sea, which on a regular basis led to flood tides, damaging the city. Already in the 16th century, the Venetians tried to avoid this, by diverting all the major rivers flowing into the lagoon, which eventually resulted in an ever-deeper lagoon environment. Still almost every year, especially in autumn and winter, the so-called “acqua alta” (high tide) causes floods in the lower points of the city, like the famous San Marco square, the lowest point of Venice (64 cm above sea level). The city had to come up with new provisional solutions (Comune di Venezia, 2005), like drainage systems, elevations, little ramparts, iron plaques in front of houses, convex sidewalks etc., which can often be seen on the streets of Venice (pictures – SET 2).

Picture Set 2

In 2003, under the supervision of Berlusconi, Venice decided to take more drastic measures with the launch of the MOSE project, the construction of an artificial dam under the water in three places on the coast of Venice, which can come up when the tide is out. (Umgiesser, 2020) The project also faced a lot of criticism, as it was incredibly expensive, it would have a negative impact on aquatic fauna and flora, and it did not even offer certainty of success. (e.g., Water Technology 2019) After a long period of corruption and mismanagement, big floods in 2019 with unforeseen damage provided an acceleration in the building process. In 2020 the project was finished and proved to be efficient, so the city of Venice finally seems protected from the water floods (Umgiesser, 2020).

Water as a cultural element

If on the one hand water informed much of the practical aspects of people’s everyday life in Venice, on the other hand, it became part of the symbolic grammar of the city. In the region we explored, there is no lack of references to the sea, navigation, water, aquatic life, and so on. Many of those references are quite literal, but some merely gesture towards the topic of water, establishing a metaphorical relation. Moreover, some of the images and texts become part of the symbolic ecology by “accident” or by a process of recontextualization of other imagery. We identified three ways in which water plays a role in forging the symbolic grammar of Venice: as memorialization and contemporalization of past practices and events; metaphorical relations and the establishing of an identity; and processes of recontextualization and negotiation of the local and the global. We should note, nonetheless, that those occurrences often overlap, revealing a multilayered symbolic grammar in the linguistic landscape of Venice.

Memorialization and contemporalization, for example, can be seen in the aforementioned [once utilitarian] cisterns, which now function as adornment and relics. The mark on the Basilica’s external wall (Image L) memorializes, we suspect, the flood of 1902, evoking affects that highlight paradoxically the fragility of “firm land” and the permanence of brick walls. The ever-present gondole (Images M and N) are also an example of contemporalization of past practices that helped to forge the identity of Venice in the global and touristic imaginary: as mobile structures that are no longer means of transportation, but ways of offering the curious tourist (in several possible languages) a way of “authentically” (Kirshenblatt Gimblett, B.; and Bruner, 2012) experiencing the water.

Images L, M, and N

This imaginary is translated and articulated into imagery. In some cases, this imagery is part of the construction of a Venetian identity catered to tourists and visitors. For example, the bucintoro miniature (Image O) materializes Venetian history and rituals in a transportable souvenir. However, water is also a core element in the visual identity and in the discourse of locals and natives of Venice. It is present, for instance, in commercial branding (Image P) and in activist and political ephemera. Image Q, a poster from Morion Laboratorio Ocuppato (@cso_morion on Instagram), shows the organization’s logo, a squid. The animal is, due to the Lab Morion’s efforts in advertising its events and actions, present in every corner of Venice where the posters inhabit. Similarly, in the protest poster in Image R, aquatic animals not only populate the visual landscape but are invoked as symbols of resistance to perceived threats to Venice’s existence.

Images O, P, Q, and R

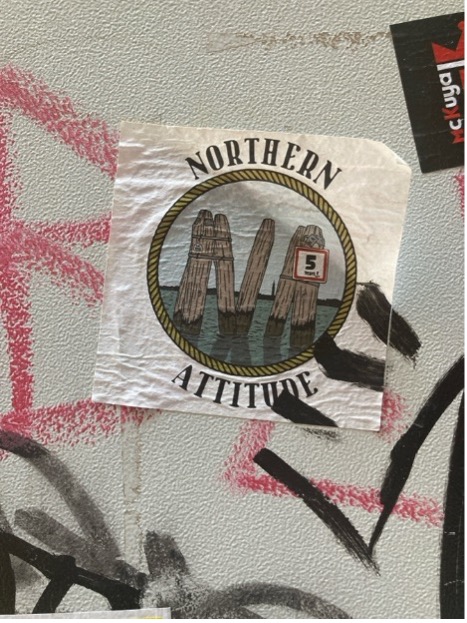

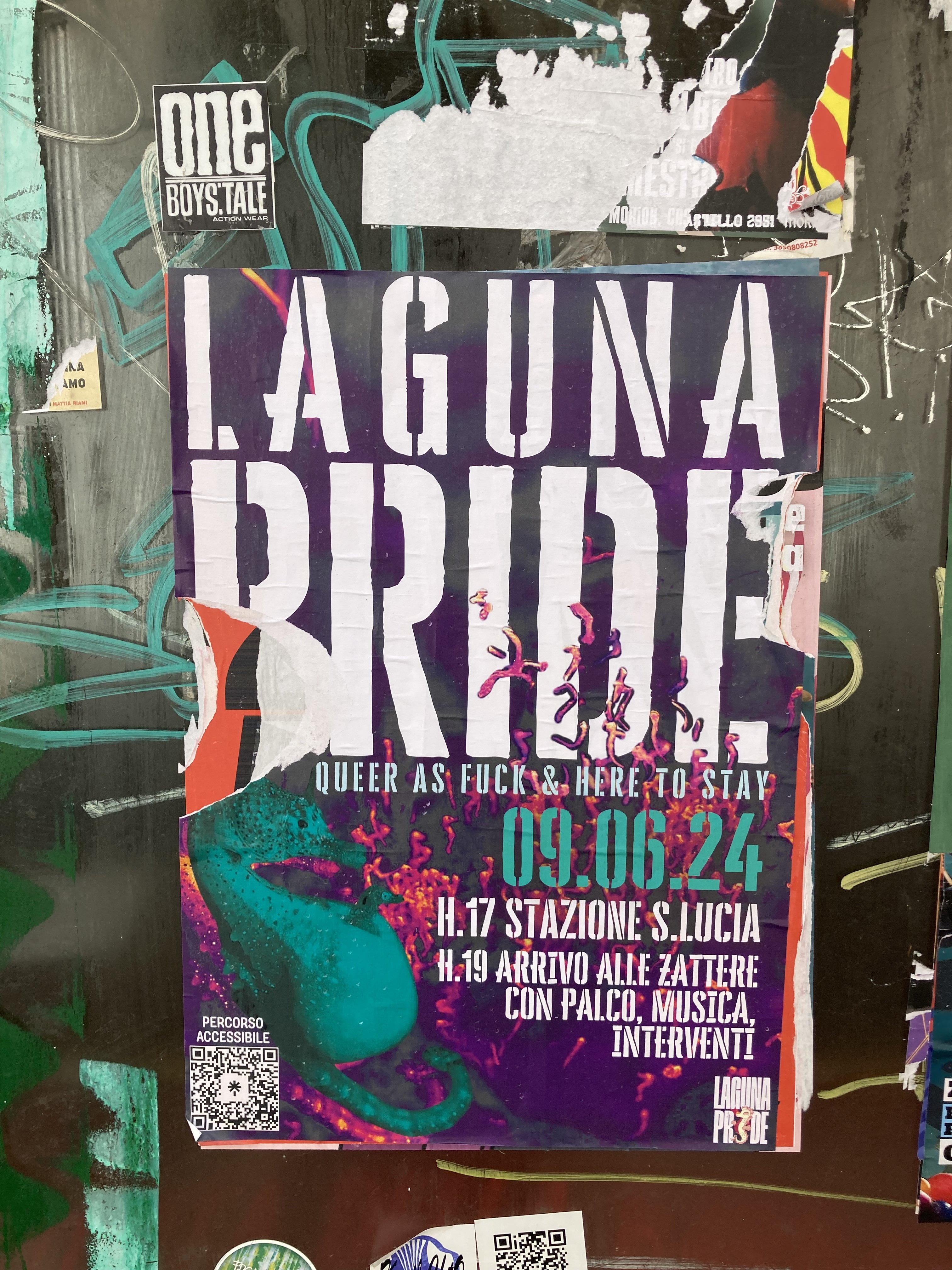

Finally, water is an element that foregrounds not only Venice’s uniqueness but also its connectedness with discourses elsewhere. The kalamarinios (@kalamarinios on Instagram) sticker (Image S) is an artistic intervention that can be found in several places outside Italy, but it gains a different meaning due to its emplacement (Scollon & Scollon, 2023). As observed in Lab Morion’s posters, the squid is not a neutral image in the Venetian landscape. Kalamarinios becomes, thus, part of the local landscape while also present in landscapes as far as the Czech Republic. Being part of international discourses can be used for political goals as well. The Laguna Pride poster (Image T) uses the seahorse as its central image.

Images S and T

While the animal brings to the forefront the links between Venice and water, metonymically represented by the reference to the Laguna, it also evokes discourses on queerness (more specifically transness and transmasculinities) very present in the anglophone world (see, for example, J.C. Pankratz’s play Seahorse; Mackenzie’s piece on queer animals for Greenpeace International; and BBC-sponsored documentary Seahorse: The dad who gave birth, directed by Jeanie Finlay). Water imagery, thus, functions both as a mark of Venice’s uniqueness and its position within global discourses.

Final considerations

Exploring the surroundings of Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, we came across many examples of how water informed and continues to inform social, economic, and cultural practices in Venice. Naturally, these phenomena are not restricted to this particular region and, one could claim, not even particular to the city. Nonetheless, the salience of water and water-related elements in the architectural, semiotic, and linguistic landscapes is an invitation to further exploration of the conditions that make Venice ever-present in people’s imaginary all over the world while suscitating all sorts of affects in natives, locals, and visitors alike. The structures, signs, and images presented here are just a scratch on the surface of the multilayered landscape of Venice, and the analyses reflect the authors’ own experience of the region, colored, expanded, and often limited by our academic, linguistic, cultural, and social backgrounds.

References

Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo. http://santigiovanniepaolo.it

Comune di Venezia (2005). Proposte progettuali alternative per la regolazione dei flussi di marea alle bocche della laguna di Venezia. 383.

Kalamarinios. https://www.instagram.com/kalamarinios/

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B.; and Bruner. (1992). Tourism. In Bauman, R. (ed.) Folklore, Cultural Performances and Popular Entertainments. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. MIT Press.

Mackenzie, W. (2021, June 29). The rainbow ocean: 6 ocean species to celebrate Pride month with. Greenpeace International. https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/48575/rainbow-ocean-6-ocean-species-celebrate-pride-month/

Morion Laboratorio Occupato. https://www.instagram.com/cso_morion/

Psarra S. (2018). The Venice Variations: Tracing the Architectural Imagination. London: UCL Press.

Scollon, R., & Wong Scollon, S. (2003). Discourses in Place: Language in the material world. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203422724

Seahorse by J.C. Pankratz. New Play Exchange. https://newplayexchange.org/plays/1678853/seahorse

Seahorse: The dad who gave birth. https://seahorsefilm.com/

Umgiesser, G. (2020). The impact of operating the mobile barriers in Venice (MOSE) under climate change. Journal for Nature Conservation, 54, 125783.

Water Technology (2019). Water technology (downloaded 2019) MOSE project. Venice, Venetian Lagoon: MOSE Project. https://www.water-technology.net/projects/mose

Zanchettin, D., Bruni, S., Raicich, F., Lionello, P., Adloff, F., Androsov, A., … & Zerbini, S. (2021). Sea-level rise in Venice: historic and future trends. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 21(8)

You must be logged in to post a comment.