Ignes Bordwell-Vezzaro, Kaiko Lenhard, Qianxue Li, Miriel Vandeperre, Michelle Wyseure

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven; Richard Toye, University of Exeter; Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Independent researcher; Luca Pes, Venice International University; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

In this blog, we present our exploratory study of the linguistic landscape of the neighbourhood surrounding the Chiesa dei Santi Apostoli di Cristo in Venice. By the term linguistic landscape, we refer to “the visibility and salience of languages on public and commercial signs in a given territory or region”, as defined by Landry and Bourhis (1997). The fieldwork was carried out in the context of the VIU Summer School ‘Linguistic Landscapes: Using Signs and Symbols to Translate Cities’ that took place from June 24 until June 28, 2024. Our survey of the area focused on how bottom-up street communications (meaning those not put up by the city and its officials) differ between residential areas, more frequently utilised by locals, and busy thoroughfares frequented by large amounts of tourists.

Insula

The insula of Santi Apostoli in Venice, located in the Cannaregio district, is divided into two significantly different sections: a vibrant commercial area and a quiet residential zone. The Strada Nova, a bustling thoroughfare, characterises the commercial section with its lively atmosphere, attracting both tourists and locals. This area is lined with shops, cafes, and restaurants, reflecting Venice’s commercial vitality and serving as a hub for social and economic activity. In stark contrast, the residential area behind the Strada Nova and the Church of the Holy Apostles offers a serene escape from the bustling main street. Narrow streets and small squares reveal a quieter side of Venetian life, with the Campo dei Santissimi Apostoli serving as dividing line. This square and the surrounding streets showcase historic homes and everyday Venetian existence, emphasising a slower pace and a more intimate community feel.

The history of the insula of Santi Apostoli in Venice is deeply intertwined with the development of its notable landmarks. The building and subsequent improvements of the Church of the Holy Apostles (Chiesa dei Santi Apostoli), dating back to 643 AD, played a significant role in shaping the commercial aspects of the surrounding Venetian area. Central to community life and adorned by architects like Mauro Codussi and Alessandro Vittoria, the church became a focal point that influenced neighbouring buildings. This influx of commercial activity laid the foundation for the area to develop into a vibrant commercial district, a trend further solidified by the 19th-century construction of the Strada Nova as part of a project by Niccolò Papadopoli to provide better pedestrian access between Rialto and the train station (Romanelli, 1988, 412-6.). The project cut through the fabric of the insula, demolishing buildings and narrow streets in order to impose an alien organisational principle focused on the traffic of large amounts of people (Ibid.). This bustling thoroughfare cemented the area’s status as a bustling centre of trade and commerce in Venice’s rich urban landscape and is in its very history connected to the divide between the local neighbourhoods and the tourist fare we will explore in this text.

Frontstage vs Backstage

Vital for social encounters, political representation, and self-expression, public space is where publics gather and connect, shaping cityscapes through perception and impromptu actions (Orhan, 2022, p.204). Given the indistinct duality and dynamic between publicness and privateness (ibid.) and the time-specific characteristic of space (Lefebvre, 1967, p. 10), linguistic landscape study allows us to reflect on a certain moment in a static fashion (Lu, 2023).

The frontstage and backstage theory can be a useful tool for interpretation. Frontstage is for the public and services, where individuals are aware of being watched and act habitually, intentionally, or subconsciously to a scripted routine or societal norms and expectations; while backstage, a safeguarded private space, is free from all those and allows people to reveal their true selves (Goffman, 1956, p.66-132; Lu, 2023). Viewing tourism in this framework, backstage refers to the authentic daily life of the hosts, while cultural representations presented to tourists constitute frontstage (MacCannell, 1976, p.91-96; Wang, et al., 2024, p.3).

During our exploration, we noticed that the main streets were extremely crowded and bustling with business activities. However, just a few steps away, the adjoining alleys seemed quiet, or even deserted, with several nameless vacant dwellings and closed restaurants and hotels. As Venice suffers from housing problems and over-tourism, these may suggest the transformations of space functions—(residential) private backstage gave way to public service frontstage, being (unsuccessfully or over-rapidly) commercialised or reoriented. Consequently, what has emerged are ‘tourist spaces,’ where visitors are often perceived as intruders who inevitably disturb the local balance (Urry, 1990, in Zanini, 2017, p. 165).

Here is a linguistic landscape showing how frontstage and backstage are negotiated through ‘staged authenticity’, the phenomenon where the backstage is (re)presented on the frontstage (MacCannell, 1999, p.96-100; Urry, 1990, p.9). In the following photo, such a gate (common in our region) divides two public areas: the bustling main street and an alley whose entry is only symbolically restricted. This creates a scenario where privacy control and management (backstage) is staged within a publicly accessible passage (frontstage), regulating outside interactions. These gates requalify public alleys as Privately Owned “Public” Spaces, potentially shifting them to semi-public or quasi-public status; by influencing how public space is perceived or experienced by the public, the transformation intends for subtraction rather than enhancement of public amenities (Radović, 2020, p.315).

An example of the gates: the ability to control connectivity, and thereby to be more or less private, is an essential characteristic of good-quality human and urban spaces as conflicts and conflicting freedoms can be mediated (Mehaffy & Elmlund, 2020, p.461).

Irregular use of Infrastructure

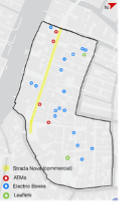

(Map of insula)

One highly visible phenomenon on the insula is the irregular use of infrastructure for informal communication along Strada Nova and in residential areas. While many infrastructure elements with smooth surfaces attract stickers and graffiti, the most striking contrast is between the types of communication on ATMs along major roads and the square in-wall ENEL electrical boxes in residential streets. Due to their unique placement – flush with the wall instead of in front of it like rain pipes or fire hydrants – ATMs and ENEL boxes are neither entirely part of the building nor wholly public space. They are privately owned, but public-facing and two-dimensional. As bottom-up communication is rarely removed from them unless it impedes functionality, they can serve as informal canvases and noticeboards.

ATMs

(Stickers on a cash drop box on Strada Nova, Venice)

The highly visible location of ATMs turns them into attractive spaces for public discourse and protest – addressing passers-by as well as the briefly captive audience of ATM customers. The stickers found here are generally high-contrast or brightly coloured and while some have messages from commercial actors, such as a recurring round sticker advertising a tattoo shop, others reference broader societal discourses, such as a yellow sticker drawing attention to the issue of carbon emissions and burning fossil fuel or stickers criticising capitalism. Others have less direct messaging but multiple axes of intertextual reference, such as a sticker reading ‘Sam was here’ that is, on the one hand, an homage to the ‘Straight Outta Compton’ logo, which is itself a reference to the US ‘Parental Advisory’ warning label. On the other hand, “[Name] was here” stickers also reference more well-known examples like ‘BNE was here’ or the “Kilroy was here” graffiti of World War II.

(Graffiti on an ATM near Ponte San Felice, Venice)

In a striking departure from the usual pattern where bottom-up expressions of speech do not interfere with the functionality of ATMs and are removed infrequently, one particular instance stood out: black paint had been sprayed directly on the ATM screen, rendering it unusable, while the adjacent wall bore the slogan ‘Free Palestine’, also in black spray paint. Just two days after capturing this image, all traces of the graffiti had been meticulously removed, erasing the visual protest.

Electric Boxes

(Example of minimally altered ENEL box)

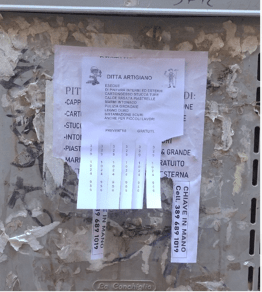

We now move on to our second unit of analysis – ENEL (Italian National Board of Electricity) electricity boxes. These boxes appear in the linguistic landscape of the city mostly through graffiti (often illegible) but, more poignantly, through their repeated usage as public notice boards for and by Venetians. The most common sights are trade workers offering their services, or homeowners seeking them. The practice does not appear to be restricted to the specific period of our visit – scraps of older, similar notices could often be seen.

(example of trade workers offering their services, pasted over a homeowner looking for worker for a restoration project)

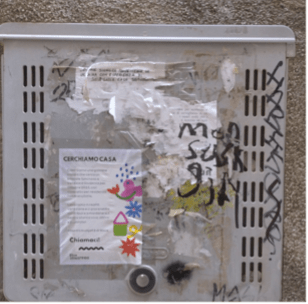

Other types of local services are also advertised, as well as requests for housing. In the image below, a Ukrainian woman offers her services as a house cleaner, and a couple working in retail advertise their need for a home. It is interesting to note that they know their audience. They advertise to the Venetians living in Venice, making it clear the value they place on keeping the historic centre ‘alive, active, and populated.’ They know their target audience – Venetian homeowners – and know how and where to reach them – with a message of regard for their lives in the city, posted on the electric boxes they often use to communicate.

(electricity box including messages from a young couple searching for housing and a Ukrainian woman searching for work)

This couple’s messaging allows us to open a brief aside on a salient social issue in Venice. As frontstage dominates, the backstage diminishes, and residents feel frustrated that their private lives and ownership are being eroded by touristic pressures (Zanini, 2017, p.166.) Gentrification ensues, transforming urban areas into exclusive markets proliferating entertainment and tourism venues (Gotham, 2015, in ibid.). This shift has enriched the frontstage, raising living standards, convenience, and property values, but has also driven out residents to more affordable locales, leaving behind a disproportionately high number of vacant homes repurposed for tourism-focused businesses, including second homes and properties owned by non-residents (ibid., p.170-172). We can see this conflict manifesting itself through informal communications in the linguistic landscape.

(A real estate firm speculatively approaches homeowners, reflecting interests in encroaching on residential areas)

(A university requests affordable housing for students and staff, indicating local housing market challenges)

Such tensions mirror the ongoing struggle between preserving private, community-oriented spaces and meeting the demands of commercial and developmental interests. The landscape of a city invites collaborative customisation and emphasises socio-cultural attributes over top-down pre-settings. The separation of our research area into two zones (one touristic, the other Venetian and residential) is an acknowledgement of these social tensions in the city, and an attempt to observe their impact in the linguistic landscape. In other words, since the audiences that interact with the ATMs and electric boxes differ (although at points certainly overlap), what differences can we observe in their messaging? What different priorities shine through?

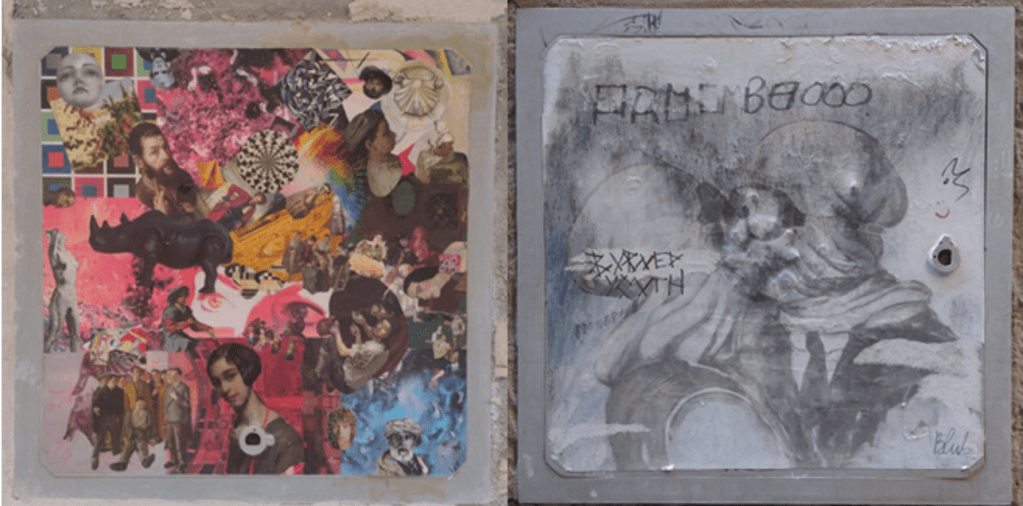

Finally, it must be said that it is not our intention to misrepresent the ‘neighbourhood notice board’ style usage of the ENEL boxes or the intensive usage of ATMs as places for bottom-up messaging as a totalising reality. Regarding the ATMs, two were almost completely devoid of stickers, which we attributed to their placement in more peripheral, less visible parts of Strada Nova, which would void them of the function of places for speech acts seeking the highest amount of visibility. For the ENEL boxes, interesting examples of alternative usage stand out, such as a faded artwork by (or at least in the style of) northern Italian street artist Blub, and two collages utilising figures from iconic art pieces. Albeit stirring images which could warrant their own extended discussion, these were only three out of three dozen electric boxes we found within the insula and are the exception rather than the rule. In contrast, 20 boxes had been outfitted with still recognisable neighbourhood notices (and even more could have existed – we cannot discount the possibility of notices on the remaining boxes having been torn up or unmade by the weather).

(A collage by an unknown artist and a (vandalised) artwork by Blub or an imitator)

Conclusion

In conclusion, by examining commercial and residential areas, we sought to highlight the dynamic interplay and contrasts between frontstage tourism activities and backstage local life. Our analysis has shown that the ATMs and ENEL boxes serve as attractive canvases for bottom-up messages, showcasing the community’s voice, but are often used in differing manners, in accordance with the audience that is being targeted. The ENEL boxes were usually outfitted with messages pertaining to the daily lives and work of locals. The ATMs, on the other hand, were often used as high-impact canvases for statements which sought the wider audience provided by a busy tourist-filled thoroughfare, including political statements, protests, and promotion of businesses.

Sources

Goffman, E. (1956). The presentation of self in everyday life. University of Edinburgh, Social Sciences Research Centre (Monograph No. 2).

Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X970161002

Lefebvre, H. (1996 [1967]) The Right to the City and Theses on the City, the Urban and Planning. In: Writing on Cities-Henri Lefebvre, Kofman, E. and Lebas, E. (eds). Blackwell: Oxford, pp. 147–159 and 177–184.

MacCannell, D. (1999). *The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class* (Revised edition). University of California Press.

Mehaffy, & Elmlund, P. (2020). The private lives of public spaces. In Companion to Public Space (1st ed., pp. 457–466). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351002189-37

Orhan. (n.d.). The Use of Semi-public Spaces as Urban Space and Evaluation in Terms of Urban Space Quality. In Urban and Transit Planning (pp. 203–212). Springer International Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97046-8_16

Radović (2020). The skyscraper and public space: An uneasy history and the capacity for radical reinvention. In Companion to Public Space (1st ed., pp. 309–319). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351002189-24

Romanelli, G. (1988). Venezia Ottocento: L’architettura, l’urbanistica. Albrizzi.

Urry, J. (1990). *The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies* (1st ed.). SAGE Publications.

Wang, Y., Edelheim, J. R., & Zhou, J. (2024). Tourism commercialisation and the frontstage-backstage metaphor in intangible cultural heritage tourism. Tourist Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687976241251514

Zanini, S. (2017). Tourism pressures and depopulation in Cannaregio: Effects of mass tourism on Venetian cultural heritage. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 164-178. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-06-2016-0036

卢德平 (Lu, D.P.). (2023). 城市空间的语言表征 (Language Representation of the City Space) [Seminar]. Bilibili Live Streaming (ID: 22327813). URL: https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1vC4y1M72E/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0

You must be logged in to post a comment.