Katie Baker, Emily Cooper, Gabriel Labrie, Nicla Pennacchio, and Esther Roza

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven; Richard Toye, University of Exeter; Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Independent researcher; Luca Pes, Venice International University; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

As part of the Summer School, Linguistic Landscapes: Using Signs and Symbols to Translate Cities, our team was tasked with carrying out a case study starting from the Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari Basilica in the sestiere of San Polo, Venice.

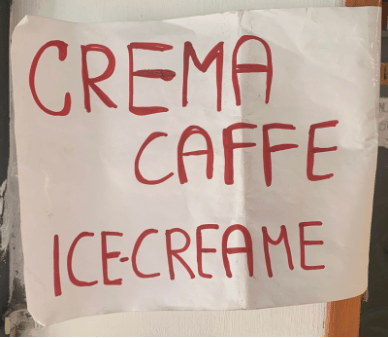

While exploring the area around the Frari, we noticed the following sign in front of a bar:

What does this divergent text tell us about the potential audience? What do the spelling mistakes tell us about the owner or the creator? (cf. Spolsky Handwritten bottom-up sign with divergent text 2008, 31). in Italian and English (Calle de le Chiovere)

The questions raised by this image piqued our curiosity about multilingual signage. Therefore, we decided to focus on signs containing more than one language (cf. Backhaus 2005 on Tokyo and Moser 2020 on Luxembourg City). Due to time constraints, the shaded area of the sestiere was omitted for this analysis, thus limiting our evaluation to the streets immediately surrounding the Santa

Maria Gloriosa dei Frari Basilica, which permeates the insulae of Frari and Nomboli. We also examined the shortest path from the Basilica to its closest vaporetto stop, San Tomà, as this is a common route taken by ourselves and other tourists (cf. Lynch 1960, 46−49).

Furthermore, only signs of the A4 format or larger were included. The size and language criteria allowed for systematic, thorough data collection in the defined area. Our final corpus accounts for 105 signs.

Duplication

From the start of this project, we knew our perspectives of Venice and its sestieri would be biased due to our various identities: as tourists, students and our individual abilities, interests and backgrounds. For these reasons, we considered how we could best analyse the sestieri through an objective lens; using statistics with taxonomies, to challenge our perception.

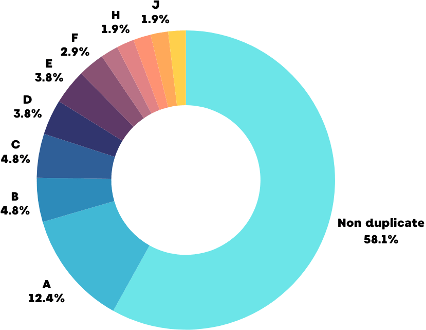

Out of the 105 signs we catalogued there were 44 duplicate signs; the purpose of the majority of these duplicates was to advertise, as opposed to providing information or warnings. This suggests the types of posters duplicated were funded by organisations that had the means to do so, and therefore able to maintain this status. This is evident as the most duplicated signs advertise culture exhibits. This begets the question of who is the intended demographic: locals or tourists?

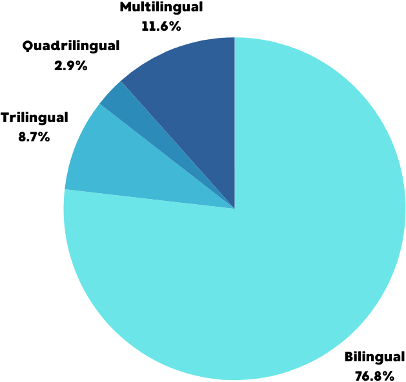

As short-term visitors in Venice, this dichotomy permeates every part of our analysis, as well as the setting of Venice itself as a popular tourist destination. This is further emphasised by the polarity between bilingualism and other forms of multilingualism – as stated in the following chart.

Many of the duplicate signs also featured the correct legal documentation needed in Venice. This suggests that there is a level of control over how Venice is perceived and that it must be driven by those with the funds. This curation is catered towards tourists which aids in maintaining this economy and provides little for the locals; who must hand make their signage on a smaller scale.

Discourses

As previously mentioned, a specific set of signs has been analysed as part of the field research, for which several taxonomies apply.

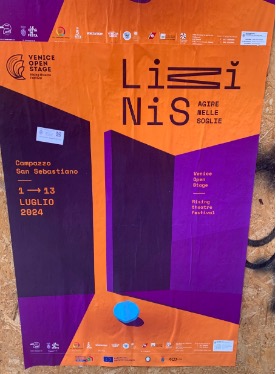

One of the different perspectives used to approach such signs is an attempt to categorise them based on the type of taxonomy they represent, and the “artistic” discourse is observed extensively.

Despite appearing monolingual, the peculiarity of this sign lies in its being written almost completely in Italian. The title reads “LIMINIS”, a genitive of the Latin word limen, which translates to doorstep or threshold depending on the context, used to advertise a theatre festival. The Italian subtitle “AGIRE NELLE SOGLIE” which translates to ´acting in the thresholds/doorsteps´ adds to this sort of exchange taking place in the thresholds, involving a mixed meaning and feeling of separation and continuity between inside and outside.

The graphics used in the poster connote a doorway which accompanies the title, emphasising the use of liminal space and culminating in this powerful example of a multimodal sign.

Bottom-Up Private Signs

Our corpus highlights bottom-up private signs, these are signs in which the creator deliberately chose to include languages other than Italian in their advertisements. This of course can signify multiple implications; openness for instance.

For example, this sign with ‘Open’ is written in multiple languages. We see “APERTO” at the top of a cardboard/solid board which we can assume was written first. Underneath it is a printed sign with the same “APERTO” in typed letters to which the words “OPEN”, “ABIERTO”, “OUVERT”, and “GEÖFFNET” were added, in handwriting. The owner here decided to expand their reach by adding the word open in more languages.

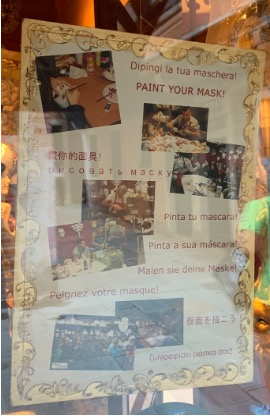

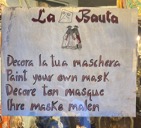

We see the same type of pattern in the commercial signs in the following images:

Although these can be perceived as an openness towards people speaking in languages other than Italian, it can also be seen as a commercial tactic. These are two different shops advertising mask-making workshops that both advertise in more than 2 languages, perhaps also attempting to rival each other.

Since these signs display more than 2 languages, it raises a question of whether this would expand their reach further than the signs only displaying English and Italian.

Nevertheless, beyond these superficial commercial tactics, could it be that the decision to exploit or exclude certain languages from Venice’s signs points to a more implicit, yet subtle, bias towards those visiting the city? More specifically, are languages being selected in a way that aims to exclude groups of individuals from the city’s own discourse, allowing only certain individuals to access the information presented through signage? Take the following sign as an example:

At first glance, we are faced with a seemingly innocent tourist-focused sign, indicating the price of entry, visiting hours, and clothing permitted when entering the infamous Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari Basilica. However, delving beneath the surface, it could be assumed that the decision to translate select parts in different languages (for example “audio guide”), constitutes a tactic that allows authorities to actively address specific nationalities whilst excluding others.

This becomes particularly evident when we consider the section of text referring to ‘“i residenti nel Comune di Venezia”’, which states that ‘Residents of the municipality of Venice can enter free of charge by showing their ID card at the ticket office’, written exclusively in Italian. This poses the following questions: why are Venetians addressed in standard Italian, rather than Venetian dialect? Surely, this would be an effective method of tackling the gradual extinction of such dialects within the Italian context. Yet, apart from the fact that one of the defining features of dialects is their almost exclusive use in oral communication, it would be a discrepancy in terms of audience design to write an official message regarding the exemption from the entrance fee to one of the prominent, world-known monuments in Venice in the local dialect. Also, since not all residents of Venice were born and raised with the local dialect, the use of standard Italian, which may be assumed to be omnipresent among all residents of this Italian city, seems to be the optimal choice in this situation. On a deeper level, these first observations raise interesting research questions about the ideologies and implicit bias held by those who create this type of signage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we must consider that with more time and fewer geographical constraints, we could conduct a more thorough examination of the area and varying taxonomies in more detail. One option we could consider concerns the method of data collection; which we could apply to the taxonomies of linguality or distribution etc. Especially the method of eye-tracking which proved extremely effective at this stage and seems to have great potential in the field of applied linguistics and semiotics (see, among other studies, Chana et al 2023). In our analysis, we were able to review the use of multiple languages on public bottom-up signs to present the varying dichotomies around the Frari.

Bibliography

- Backhaus, Peter. 2006. Linguistic Landscapes: A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo. 136. Bristol; Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

- Chana, Kirren, Jan Mikuni, Alina Schnebel, Helmut Leder. 2023. Reading in the city: mobile eye-tracking and evaluation of text in an everyday setting. Frontiers in Psychology. Section Perception Science, Volume 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1205913

- Lynch, Kevin. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England: The MIT Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Moser, Philippe. 2020. Linguistic Landscape als Spiegelbild von Sprachpolitik und Sprachdemografie?: Untersuchungen zu Freiburg, Murten, Biel, Aosta, Luxemburg und Aarau. Tübinger Beiträge zur Linguistik 572. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2008. ‘Prolegomena to a Sociolinguistic Theory of Public Signage’. In Linguistic Landscape. Expanding the Scenery, edited by Elana Shohamy and Durk Gorter, 25−39. New York: Routledge.

You must be logged in to post a comment.