Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

From the female freedom fighters of the Haitian Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement and Kamala Harris’s foreign policy, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history.

‘In some cases, it was the women who were fiercest in the fight’: The female freedom fighters of the Haitian Revolution

Emi Eleode

BBC

On the night of 23 August 1791 in Cap-Français, on the north coast of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti), fires raged on the plantations. The enslaved set fire to the buildings and fields, and killed their masters. It was the start of the Haitian Revolution, the only known uprising of enslaved people in history that led to the founding of a state that was free from slavery.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic in France, news was fast spreading about the uprisings. The wealthy ruling elite and those with a monopoly in the transatlantic slave trade were growing anxious. They began to realise that their days of subjugating the enslaved population for profit were coming to an end. The coordinated attacks was the beginning of an armed resistance that sprung up across the country in the following years. [continue reading]

East German culture has been ignored for too long. Until we embrace it, our country will remain dangerously divided

Carolin Würfel

Guardian

When I went to school in the 1990s, GDR literature wasn’t taught or read. It was treated as something shameful. I didn’t dare to pick up a book by an East German writer, even though many of them were in our library at home in Leipzig. Looking back, I believe the reason was the public perception of the old socialist republic. It scared me off.

When the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November 1989, it marked the beginning of the end of East German art and literature. Everything that had shaped our cultural history was thought away, spoken away and written away. West Germans took sovereignty over the narrative, and their verdict was clear: the former East German state was wrong in every aspect and worth nothing. This also meant books, plays, paintings, sculptures, films and music were buried and left behind, because they too were considered wrong. [continue reading]

The CIA-in-Chile Scandal at 50

Peter Kornbluh

National Security Archive

Fifty years ago, as the New York Times prepared to break a major exposé on CIA covert operations in Chile, the architect of those operations, Henry Kissinger, misled President Gerald Ford about clandestine U.S. efforts to undermine the elected government of Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende, documents posted today by the National Security Archive show. The covert operations were “designed to keep the democratic process going,” Kissinger briefed Ford in the Oval Office two days before the article appeared fifty years ago this week. According to Kissinger, “there was no attempt at a coup.” “I saw the Chile story,” Ford told Kissinger on September 9, 1974. “Are there any repercussions?” Kissinger replied: “Not really.”

In fact, the front-page story written by investigative reporter Seymour Hersh—“C.I.A. Chief Tells House Of $8 Million Campaign Against Allende in ‘70-’73”—set in motion the biggest scandal on covert operations the intelligence community had ever experienced. Hersh’s September 8, 1974, article led directly to the formation of a special Senate committee, chaired by Senator Frank Church, that conducted the first major investigation of CIA covert actions in Chile and elsewhere and that was the first congressional body to evaluate the role of secret, clandestine operations in a democratic society. The political repercussions forced President Ford to publicly acknowledge the CIA operations in Chile while forcefully denying they had anything to do with fomenting a coup. The president’s White House lawyer subsequently advised Ford that his statement “was not fully consistent with the facts because all the facts had not been made known to you.” [continue reading]

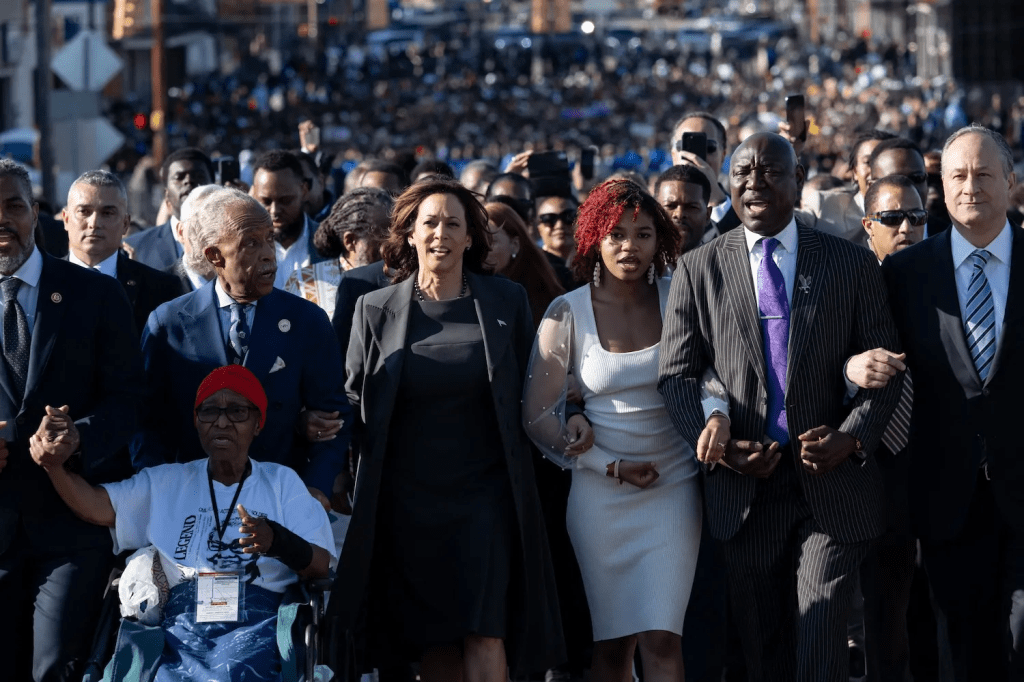

The Civil Rights Movement and Kamala Harris’s Foreign Policy

Keisha N. Blain

Foreign Policy

How might the U.S. civil rights movement inform a Harris administration’s approach to foreign policy? In a world riven by authoritarian leaders eager to capitalize on American divisions, such an approach would certainly be welcome. And the civil rights movement is arguably directly responsible for presidential candidate and current Vice President Kamala Harris’s existence: Her parents met in 1962 at a University of California, Berkeley campus study group where her father delivered a speech on the parallels between Jamaica and the United States.

While many Americans think of the civil rights movement as a distinctly U.S. phenomenon that began in the 1950s, in reality it began much earlier. Black Americans began pursuing civic equity through formal channels in the 19th century, and from the very beginning that pursuit was strategic in its international engagement. Harris’s parents—both raised as British colonial subjects in Jamaica (her father) and India (her mother)—saw the work of making the United States more equal as paramount to their lives. They engaged deeply with that work and imparted their dedication to their child. This story alone is emblematic of the global dimensions of the cause. [continue reading]

You must be logged in to post a comment.