Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

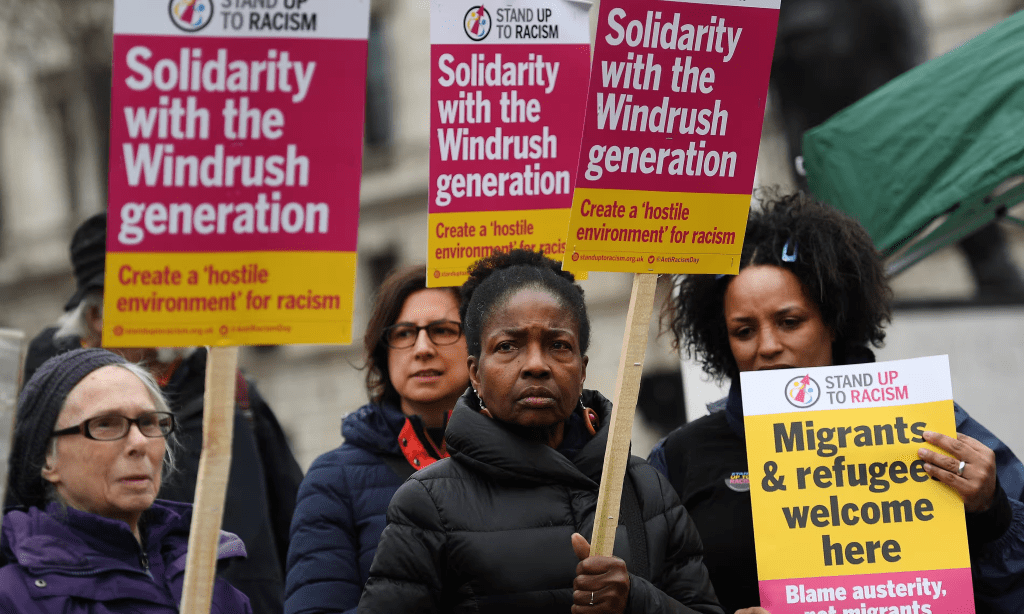

From a new critical report about the Windrush scandal to Black women comrades in the struggle for liberation, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history.

Home Office forced to release critical report on origins of Windrush scandal

Amelia Gentleman

Guardian

The Home Office has been forced to release a suppressed report on the origins of the Windrush scandal by a tribunal judge who quoted George Orwell in a judgment criticising the department’s lack of transparency. For the past three years, Home Office staff have worked to bury a hard-hitting research paper that states that roots of the scandal lay in 30 years of racist immigration legislation designed to reduce the UK’s non-white population.

The 52-page analysis by a Home Office-commissioned historian, who has not been named, described how “the British empire depended on racist ideology in order to function” and explained how this ideology had driven immigration laws passed in the postwar period. The department rejected several freedom of information requests asking for the Historical Roots of the Windrush Scandal to be released, arguing that publication might damage affected communities’ “trust in government” and “its future development of immigration policy”. [continue reading]

Forgotten story of escape from Nazis found

Danny Fullbrook

BBC

Pte Ray Bailey, from Dunstable in Bedfordshire, was among the Allied troops captured by the Germans in 1940 after the French forces at St Valery-en-Caux surrendered. The 21-year-old managed to escape captivity and travel 2,000 miles, through Nazi-occupied Europe, to Spain, where he was then transported back to his parents’ home in England. His 80,000-word account of the experience was found in an online auction won by amateur social-historian David Wilkins, who has now published it under the title Blighty or Bust.

The 69-year-old, from Portland, Dorset, bid on the box of World War Two memorabilia without knowing exactly what the contents would be. Inside, the diary collector found photographs, foreign currency and several notebooks that Pte Bailey wrote on his return to England in 1940. He said: “When it arrived, I couldn’t believe the quality of what there was. “Most published World War Two memoirs are written much later in people’s lives, but he was writing like you would write about a holiday you went on 18 months ago – he remembers it very clearly.” “I don’t think there is anything from this early in the war written by a soldier ever to be found.” [continue reading]

Knife at the Throat

T. J. Clark

London Review of Books

Frantz Fanon is a thing of the past. It doesn’t take long, reading the story of his life – the Creole childhood in Martinique, volunteering to fight for the Free French in the Second World War, his career in Lyon as arrogant young psychiatrist, the part he played in the war in Algeria, the encounters with Nkrumah and Lumumba, his death at the age of 36 – to realise that his is a voice coming to us from a vanished world. ‘Annihilated’ might be more accurate.

Yet the voice breaks through to the present. Its distance from us – the way its cadence and logic seem to shrug aside the possibility of a future anything like ours – is transfixing. Its arguments are mostly disproved, its certainties irretrievable. The writer is trapped inside a dialectical cage. That’s why we read him. [continue reading]

Black Women Comrades in the Struggle for Liberation

Maria Martin

Black Perspectives

“Dear Comrade,” began a letter from Amy Ashwood Garvey to Fumilayo Ransome-Kuti of Nigeria. In that letter sent on March 11, 1949, Mrs. Garvey went on to say “Enclosed, please find the paper which I return with thanks.”1 Both women shared a reading whose title is not mentioned but that very likely spoke to their common interests as liberation activists. By sending this paper to one another, they were sharing ideas internationally from London to Lagos. Their transnational outreach to one another indicated a Pan-African proclivity for both women as well, with Mrs. Garvey representing the Caribbean and Mrs. Kuti representing Nigeria.

This letter reveals that Mrs. Garvey and Mrs. Kuti were comrades in the struggle for global Black liberation. Both women were dynamic intellectuals, organizers, activists, Pan-Africanists, and advocates for women’s rights and development. They were both very strong willed and audacious as they took on the work of standing resolutely against oppressive regimes, institutions, and ideas that stifled the brilliance, potential, and freedom of Black people. This letter is an example of not only the connectivity of Black women activists from Africa and the Diaspora, but their intellectual thought towards building a global Black liberation movement with women at the helm. [continue reading]

You must be logged in to post a comment.