Richard Toye

University of Exeter

This post is based on a paper delivered at the recent CIGH workshop on ‘New Approaches to Imperial and Post-Imperial Politics’.

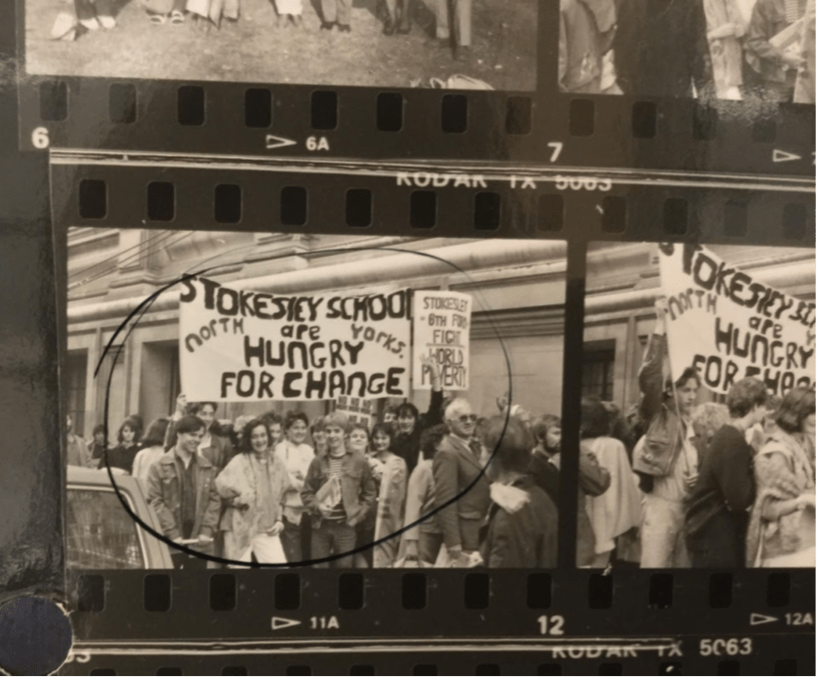

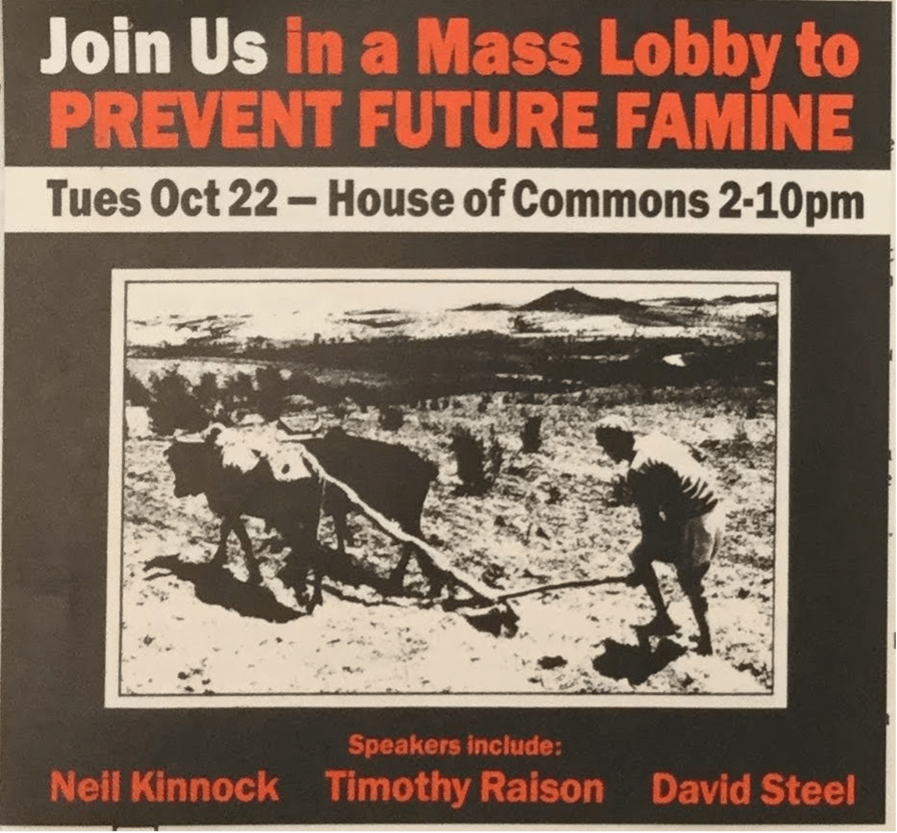

The origins of this post lie in some photographic contact sheets I discovered in the Oxfam Archive at the Bodleian Library, dating back to 1985. These captured a significant mass lobby against world poverty that took place that year. What immediately caught my eye was the slogan “Hungry for Change,” a rallying cry from the 1980s, which brought back memories of my own experiences as a teenage volunteer in an Oxfam shop in Brighton.

Not only did the mass lobby involve school children traveling all the way from North Yorkshire and other far-flung places to participate, but the photos also underscored the fact that someone, likely Oxfam itself, found it worthwhile to document the event by hiring a photographer. The day’s activities were intended not merely as a protest but as an “image-event”.

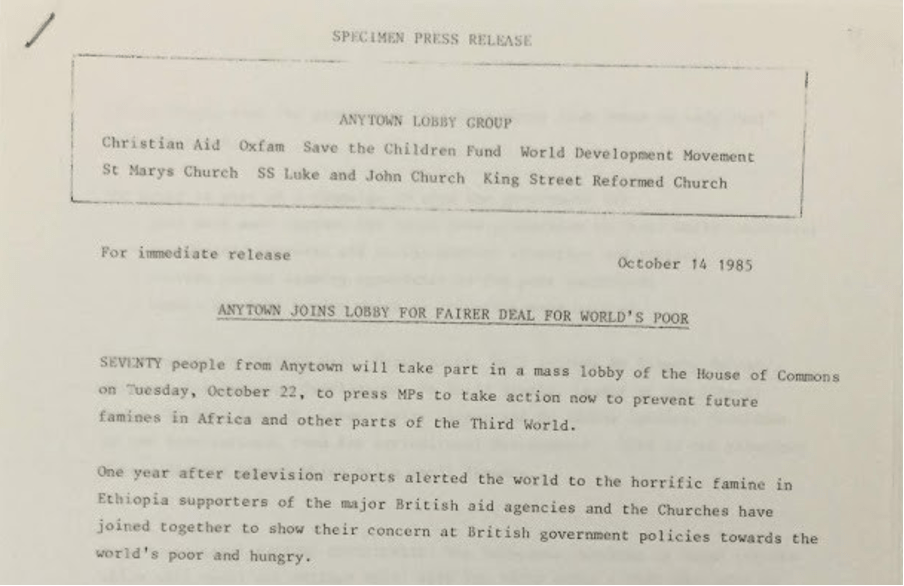

But the research I’ve done on this topic isn’t just about this one exciting day. It’s about a broader phenomenon of political activism during the 1980s, focusing on the mass lobbying efforts around aid, humanitarianism, and the struggle against poverty. This era was marked by well-organized efforts by NGOs, churches, and concerned citizens who sought to challenge the dominant policies of the time.

To understand the significance of these mass lobbies, we need to dig into the longer history of parliamentary petitioning and lobbying, as illuminated by Richard Huzzey, Henry Miller, and others. We need to consider the important role that voluntary organizations and civil society groups have played in shaping public discourse. Additionally, it’s essential to contextualize these efforts within the global political environment of the 1970s and 1980s, specifically in relation to decolonization, the discourse of the New International Economic Order (NIEO), and the rise of the so-called “Washington Consensus”.

The Washington Consensus, which advocated for free-market solutions and structural adjustment programs (SAPs), played a dominant role in shaping aid policies. The IMF and US government spearheaded this agenda, asking governments to adopt market-driven reforms, including privatization, in exchange for aid. This push for economic liberalization was resisted by activists and organizations who were critical of the impact these policies had on the world’s poorest countries.

UK aid policy, especially during the Thatcher era, was in line with these broader trends. It’s important to note that the roots of the 1980s aid policy can be traced back to the 1970s under Jim Callaghan’s Labour government, when the so-called Aid and Trade Provision (ATP) was introduced to benefit British industries. Commercial parliamentary lobbying help bring about this change. ATP continued into Thatcher’s tenure, with the aim of linking aid to UK economic interests, exemplified by inopportune initiatives such as selling British buses, regardless of their suitability, to places like Tanzania.

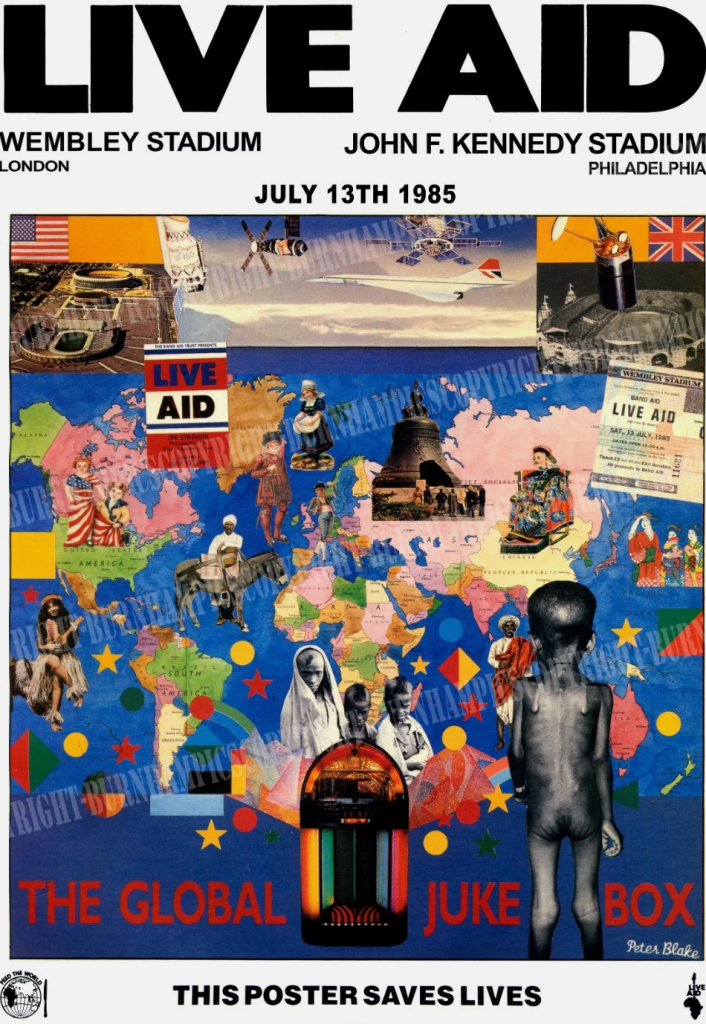

Yet countervailing trends were also at work. For many, the 1985 Live Aid concert is a vivid memory. It was a major cultural event designed to raise funds for victims of the Ethiopian famine. The event followed the Band Aid single in late 1984, which brought global attention to the humanitarian crisis. While Live Aid became a defining moment in popular culture, it also represented a broader mobilization of public sentiment around issues of global poverty and aid.

The term “mass lobby” came into use from the 1920s. Although the concept of mass lobbying originated in the US, where it often referred to coordinated campaigns involving letter writing and telegrams, the British version was more focused on physical presence. Activists would show up in person to meet with their parliamentary representatives, sometimes after demonstrating outside parliament in large numbers.

One significant precursor to the 1985 lobby was the World Development Movement’s action four years earlier. This event, built around the 1980 Brandt Report, called for larger-scale aid and a rebalancing of the world economy to address the systemic inequalities affecting developing countries. The 1981 mass lobby of Parliament saw 10,000 people mobilized to advocate for this cause, supported by an effective letter-writing campaign. There’s evidence that this forced the Thatcher government to at least pause and consider the demands being made, though of course they never embraced the recommendations of the Brandt Report.

This era also saw other significant mass lobbies, such as those organized by CND from the 1950s onwards and campaigns for gay rights in the late 1980s. What’s particularly interesting is the overlap between these movements – it’s likely that activists often participated in multiple campaigns, learning from each experience and refining their tactics.

The success of the 1985 mass lobby lay in its meticulous organization. From my research in the Church of England’s records in the Lambeth Palace Archives [Collections – Lambeth Palace Library], it became clear that having prominent visible supporters – such as Bishops – was crucial to the event’s credibility. The importance of visible leadership was especially true in the case of religious organizations, where church involvement added a layer of moral authority to the cause.

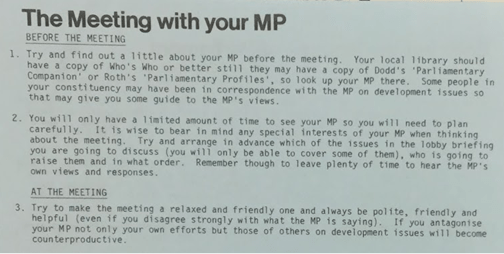

One of the key objectives of these events was to ensure that participants were well-prepared. Organizers provided detailed briefing documents to help activists understand what they were advocating for, how to engage with MPs, and how to make the most of their meetings. There was an emphasis on being polite and constructive, even when disagreeing with MPs.

The level of coordination required to pull off these mass lobbies was immense. Everything from booking travel for participants to making sure everyone met with the right MPs at the right time had to be meticulously planned. And while things didn’t always go perfectly, the impression created was considerable. The presence of celebrities such as actor (and future Member of Parliament) Glenda Jackson must have helped.

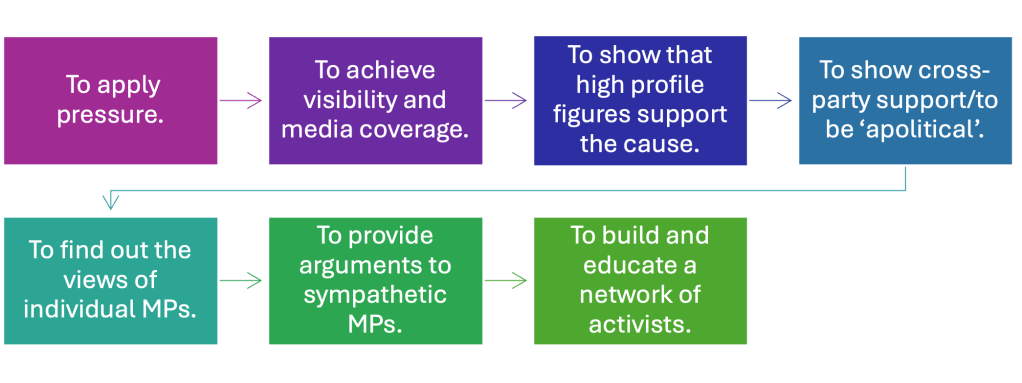

Ultimately, the 1985 mass lobby wasn’t just about changing government policy on a single day. The event helped to educate a new generation of activists, encouraging them to stay engaged and to think strategically about how to influence public policy. This long-term approach was crucial to sustaining momentum and ensuring that the message of the lobby didn’t get lost once the event was over. Whereas the broad purpose was to apply pressure to politicians, there was a lot more to that than simply having thousands of people show up on the day. The various goals were as follows:

Conclusion

The 1981 and 1985 mass lobbies represent a pragmatic and arguably effective effort by NGOs, churches, and concerned citizens to challenge the government’s neoliberal agenda. These lobbies built on tried and tested methods of activism, mobilising public sentiment and using the media to amplify their message. They also demonstrated the importance of careful planning, media awareness, and the ability to appeal across party lines.

While the direct impact of these lobbies on government policy was limited, their real success lay in building a movement. They provided a platform for educating activists, influencing public opinion, and sustaining long-term advocacy efforts. In the end, these mass lobbies were about more than just one day of action – they were about changing the way people thought about global poverty and aid, and building a network of activists committed to making a difference.

You must be logged in to post a comment.