Andreas Stucki

University of Bern

Nearly eighty years after World War II, research into the connections between Nazism, colonialism, and international development remains an underexplored area despite considerable scholarship on the complex history of development after 1945. Continued involvement of colonial development experts and bureaucrats in African late colonial states highlights how German practitioners with Nazi ties moved into new roles in imperial and international development after the Second World War.

This begs the question: to what extent might Nazi ideologies and practices have shaped postwar global development efforts?

From Nazi Economic Planners to Global Development Pioneers

The early postwar period saw many former colonial officials from European empires repurpose their expertise in international organizations and NGOs. “Recycling Empire” is the term used to describe the birth of the European aid industry.[1] Critics have long argued that development cooperation often served as a new form of imperial influence, extending the reach of the Global North into the Global South through what was termed technical and financial aid.

However, the story of German involvement is less discussed, even though it presents a similarly troubling narrative. A striking example is Johann Albrecht von Monroy, whose transformation from “Nazi agent” to “development pioneer” in the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) forestry division was recently documented by historian Martin Bemmann.[2] This case highlights how individuals with problematic pasts could seamlessly find new roles in the emerging global development apparatus.

Another example is Josef G. Knoll, a former SS member whose involvement in the Nazi regime only came to light a couple of years ago. Knoll became the head of the Plant Production and Protection Division at the FAO in the 1950s and played a key role in shaping agricultural policies. His connection with Misereor, a Catholic development agency founded in Aachen in the late 1950s, further underscores the entanglement of former Nazi figures with German and international development initiatives. The revelation of his SS affiliation led to the renaming of a research award previously named in his honor. [3]

The Case of Hermann Pössinger: From Waffen-SS to Rural Development Expert

One of the most intriguing yet obstructed case studies is that of Hermann Pössinger, a German agronomist whose career spanned from Nazi military service to significant roles in colonial and international development projects—though restricted access to crucial archives has prevented a full investigation. Born in 1924, Pössinger voluntarily joined the Waffen-SS at the age of eighteen, participating in military operations on the Western Front and later with the notorious 3rd SS Panzer Division “Totenkopf” in the Soviet Union. Following the collapse of the Nazi regime, Pössinger’s activities remain undocumented until 1947, when he enrolled in agricultural studies at the Technical University of Munich.

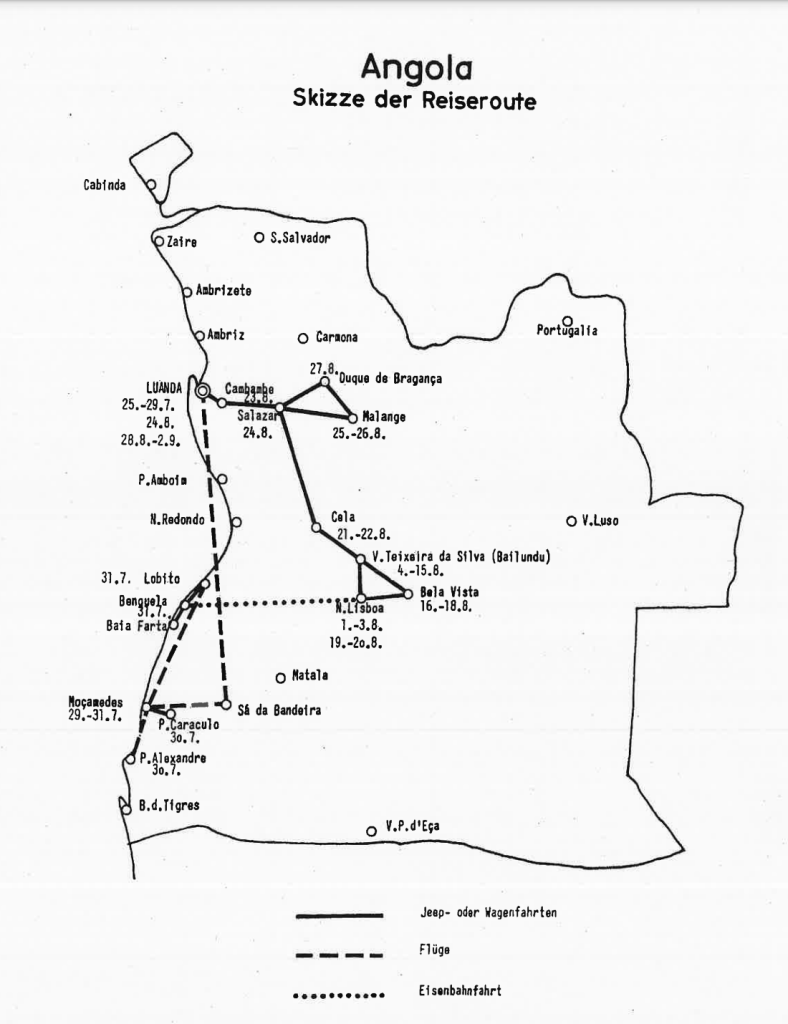

By the early 1950s, Pössinger was working on rural development projects in Brazil, gaining experience that would later define his career. In the 1960s, he secured a position at the Institute for Economic Research (ifo, Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung) in Munich, where he specialized in tropical agriculture. His fieldwork, funded in part by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, took him to Angola and Mozambique, then still under Portuguese colonial rule. His research was published in the ifo’s Africa Studies series, a collection that received notable attention at the time, as well as in scholarly collections in English and Portuguese.

As a consultant for the Portuguese colonial authorities, Pössinger worked in the central Angolan highland in a large rural development project, aiming to modernize agricultural practices and “develop” the local population. Allegedly this colonial scheme was “free from any paternalism.”[4] According to his reports, the project reached about 130,000 families, roughly eleven per cent of Angola’s African population at the time. Pössinger’s activities in Angola overlapped with projects co-financed by Misereor in the same region. Misereor became his next employer in the mid-1970s.

Institutional Entanglements and Archival Roadblocks

The continuity between Pössinger’s colonial work and his later involvement with Misereor raises questions about the extent to which development agencies knowingly engaged with individuals who had a compromised Nazi past. Misereor was well aware of Pössinger’s role as an advisor to the Portuguese colonial government. In fact, this was exactly the field experience they were looking for. Yet it is unclear how much Misereor knew about the German agronomist’s problematic past during WWII.

Attempts to fully understand Pössinger’s career and its implications face significant archival challenges. The ifo, despite receiving federal funding, claims it has no archival records or personnel files for Pössinger. This is surprising given the institute’s history and its formal affiliation with the University of Munich and the Bavarian state government since 1997. Historians Götz Aly and Susanne Heim have previously pointed to the “brown” backgrounds of ifo founders Wilhelm Marquart and Hans Langelütke.[5] How the institute handled the Nazi affiliations of staff like Pössinger in subsequent years remains unclear.

Misereor’s archival practices pose additional barriers. While its archives are extensive, access is limited to project files. Internal reports, which could shed light into decision-making processes, and personnel records are restricted, even though more than fifty years have passed since many of these documents were created, and over twenty years since the relevant individuals died. This lack of transparency hinders a thorough examination of the Catholic development agency’s historical role and its personnel decisions.

The restrictive approach of German institutions like Misereor and ifo stands in stark contrast to that of international organizations such as the International Labor Organization (ILO) in Geneva. The ILO archives are accessible, including correspondence with Misereor and personnel files of development practitioners. This openness enables researchers to critically examine the connections between colonial legacies and development practices to this day. Such access is essential for a deeper understanding of how former colonial officials and individuals with Nazi affiliations contributed to shape postwar development policies and practices. It allows scholars to interrogate the ideological continuities and the power dynamics embedded in the history of international development.

Confronting the Legacy of Nazi Involvement in Development

The reluctance of German institutions to open their archives may be rooted in a misplaced concern for privacy protection, shielding the reputation of individuals long deceased rather than facilitating historical reckoning. As time passes, this stance becomes increasingly untenable, especially given the importance of transparency in publicly funded organizations. A critical examination of the personnel records of figures such as Pössinger could illuminate the continuities between Nazism, colonialism, and postwar development efforts.

On behalf of the German government Pössinger travelled again to Angola in 1989, in the final years of his career, exploring opportunities in contributing to rural development schemes. Upon his return he published his “Reflections on Development Cooperation.”[6] Remarkably, Pössinger advocated for a project that bore striking similarities to the initiatives he had managed for the Portuguese colonial authorities in the early 1970s. This continuity in the approach again underscores the importance to critically analyze the possible persistence of colonial and eventually Nazi mindsets within the framework of international development through a biographical lens.

Andreas Stucki is an associate researcher at the University of Bern. He is the author of Las Guerras de Cuba (2017), Violence and Gender in Africa’s Iberian Colonies (2019) and, with Robert Aldrich, the co-author of The Colonial World (2023).

[1] Véronique Dimier, The Invention of a European Development Aid Bureaucracy: Recycling Empire (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[2] Martin Bemmann, “‘Nazi Agent’ and Development Pioneer: Johann Albrecht von Monroy, National Socialist Europe and Unknown Origins of FAO’s Forest Related Development Activities,” Journal of Contemporary History 58, no. 3 (2023): 424-48.

[3] See https://www.stiftung-fiat-panis.de/de/wissenschaftspreise/hei-wp .

[4] Hermann Pössinger, “Ländliche Genossenschaften in Angola: Ein unterbrochenes Experiment,” Africa Spectrum 10, no. 3 (1975): 236.

[5] Gözt Aly and Susanne Heim, Vordenker der Vernichtung: Auschwitz und die deutschen Pläne für eine neue europäische Ordnung (Frankfurt Main: Fischer, 1993).

[6] Guido Ashoff and Hermann Pössinger, “Überlegungen zur entwicklungspolitischen Zusammenarbeit mit Angola” (Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 1989).

You must be logged in to post a comment.