Chuanyou Zhou

University of Exeter

This post explores the significance of the fact that the decline of the phrase “Imperial Federation” in British imperial discourse coincided with its replacement by the term “British Commonwealth.”

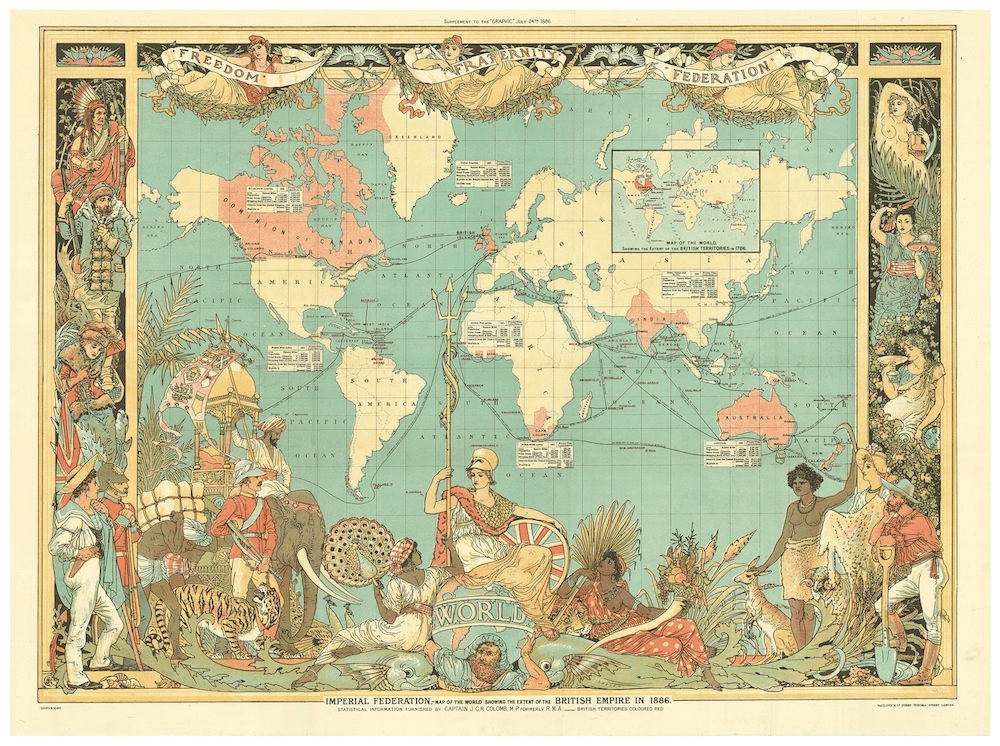

The concept of Imperial Federation was a political idea that gained public attention in the 1870s and evolved into a political movement following the establishment of the Imperial Federation League in 1884. The movement sought to unify the empire in a federal structure and counteract tendencies toward separation.

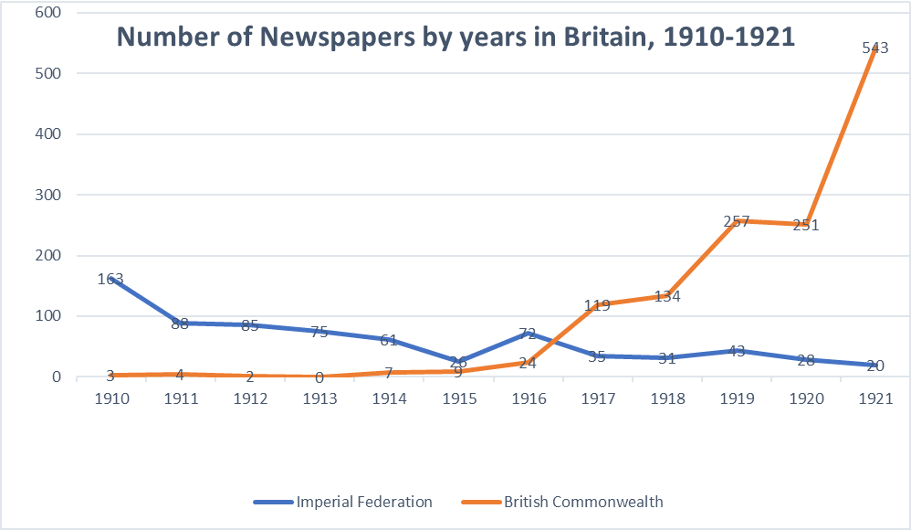

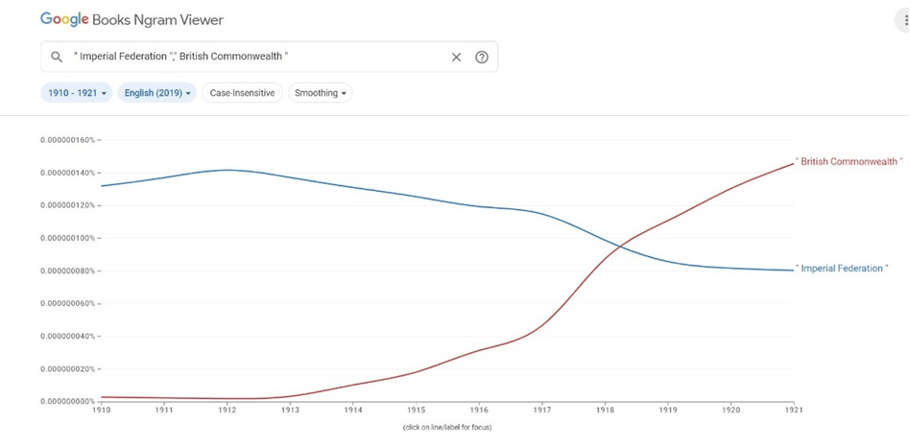

An analysis of newspapers from 1910 to 1921, conducted using the Gale Primary Sources database, reveals that the term “British Commonwealth” was rarely used in the context of the empire before 1916. In contrast, the term “Imperial Federation” saw a marked decline in usage after 1910, showing an inverse relationship with the rise of “British Commonwealth.” This trend is clearly observable in both the Gale Primary Sources database and Google Books Ngram.

Consequently, a hypothesis emerges that the term “Imperial Federation” was gradually supplanted by “British Commonwealth,” a shift largely attributed to changes in the perception of the empire following the First World War.

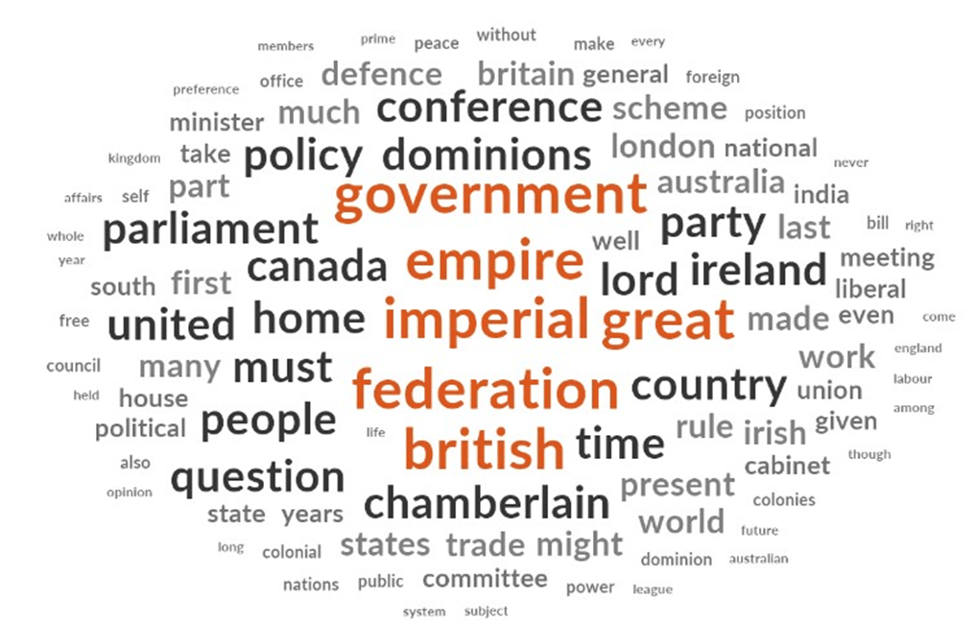

A word frequency analysis from 1910 to 1921 reveals that the terms “imperial parliament,” “Dominions,” and “Ireland” appeared frequently during this period. This suggests that the decline in the rhetoric of Imperial Federation was largely driven by opposition from the Dominions and Ireland to the concept of an “imperial parliament”.

Dominion Autonomy

The First World War provided an opportunity for the Dominions to assert greater autonomy in foreign affairs. The war highlighted the difficulties of achieving effective cooperation within the existing imperial system. Colonies were drawn into the war without their consent, exposing a fundamental flaw in the system. The Dominions recognized that decisions regarding peace and war had profound impacts on their interests, and they concluded that such decisions could not be left to others who lacked sufficient understanding of local welfare.

This aspiration was in fundamental opposition to the concept of Imperial Federation. While the Dominions valued cooperation and strong ties within the empire, they envisioned a “round table” system where all members could deliberate as equals on common actions, without interference in one another’s internal affairs. This desire for equality was reflected in the language used to describe the relationship between the dominions and the mother country. Previously, terms such as “daughter,” “parent state,” and “children” were common, but from 1919 onwards, expressions like “sister states” and “partnership” became more prevalent.

No Zollverein

Zollverein (imperial reciprocity) and Kriegsverein (common defense) were seen as the two principal foundations of Imperial Federation. Canada was the primary advocate of imperial reciprocity, hoping to counter the McKinley tariff and subsequent U.S. protectionism by promoting economic cooperation within the empire. Some Canadian politicians believed that complementary markets could be established within the empire, fostering self-sufficiency.

However, this idea faced strong opposition from British free traders. For example, Goldwin Smith, a leading figure of the Manchester School, consistently argued that Britain should abandon its colonies and that Canada should join the United States. The movement suffered a significant setback after the Conservative and Unionist defeat in the 1906 general election. By 1911, Canada began to explore renewed negotiations on reciprocity with the United States, likely due to Britain’s persistent reluctance to support imperial reciprocity.

As Canada was central to the imperial preference strategy, abandoning imperial reciprocity effectively undermined one of the key pillars of Imperial Federation.

The Elimination of German Elements

British politicians often described the conflict between the British Empire and Germany as a war of ideals rather than a war of nations. Germany’s “Prussianism,” rooted in the concept of a centralized empire, demanded unconditional obedience to the state from all social classes. The concept of Imperial Federation, tied to German origins, was associated with this model of centralization. The term itself was influenced by the German Confederation, and its principal components – Zollverein and Kriegsverein – were German in origin.

In contrast, the Commonwealth was framed as a system based on freedom, equality, self-government, and civic responsibility, rather than privilege. British politicians portrayed the Commonwealth as aiming to maintain global peace and promote human civilization, rejecting the centralized and authoritarian principles associated with Prussianism.

The emotional rejection of the German model, fuelled by the First World War, contributed to a broader disassociation from the idea of empire. Germany’s defeat symbolized the failure of the imperial system, leading Britain to embrace the term “British Commonwealth” instead of “British Empire.”

Ireland’s Rejection of Imperialism

The concept of Imperial Federation was initially proposed as a method of devolution to federate Britain. However, the affirmation of self-determination at the Peace Conference as a guiding principle for resolving post-war national conflicts undermined the feasibility of such a plan.

Granting Ireland Dominion status effectively ended the possibility of addressing the Irish issue through Imperial Federation. As a result, British politicians no longer viewed such Federation as a necessary solution to the Irish question.

Ireland demonstrated clear opposition to imperialism while expressing a preference for the Commonwealth. The Irish viewed the Commonwealth as a mechanism to challenge British authority and safeguard Irish independence, emphasizing that the Commonwealth was not an empire. It can be inferred that the shift from “Imperial Federation” to Commonwealth occurred because the latter offered a framework to address the Irish issue in a post-war context, unlike the imperial system.

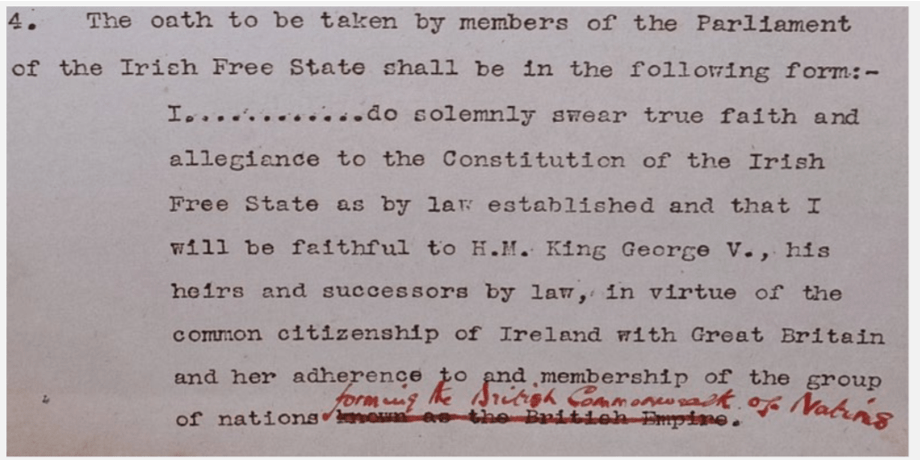

Britain’s changing attitude toward Irish self-government was evident in the rhetorical shift surrounding the issue. The draft treaty initially used the phrase “British Empire” in Article 4, but this was later revised to replace “British Empire” with “British Commonwealth of Nations.”

Conclusion

Both the mother country and the Dominions collectively abandoned the imperial terminology that once defined their relationship. The decline of Imperial Federation following the First World War is best understood as a shift from discussions about imperial unity to those centred on the “British Commonwealth.”

Before the war, the term “Imperial Federation” was frequently used to articulate a desire for imperial unification. After the war, however, “British Commonwealth” replaced “Imperial Federation,” and debates about unification and cooperation increasingly relied on this new phrase.

The question of whether “British Commonwealth” and “Imperial Federation” differed significantly remains complex. Some politicians, such as J.C. Smuts, distinguished between the two, while others, like Lionel Curtis, used “British Commonwealth” in ways that aligned closely with former ideas of Imperial Federation. Regardless of the terminology, both concepts shared the same ultimate goal: to unite all parts of the empire on an equal footing, foster efficient cooperation among them, and strengthen their mutual ties in the future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.