Matthew Hurst

University of York

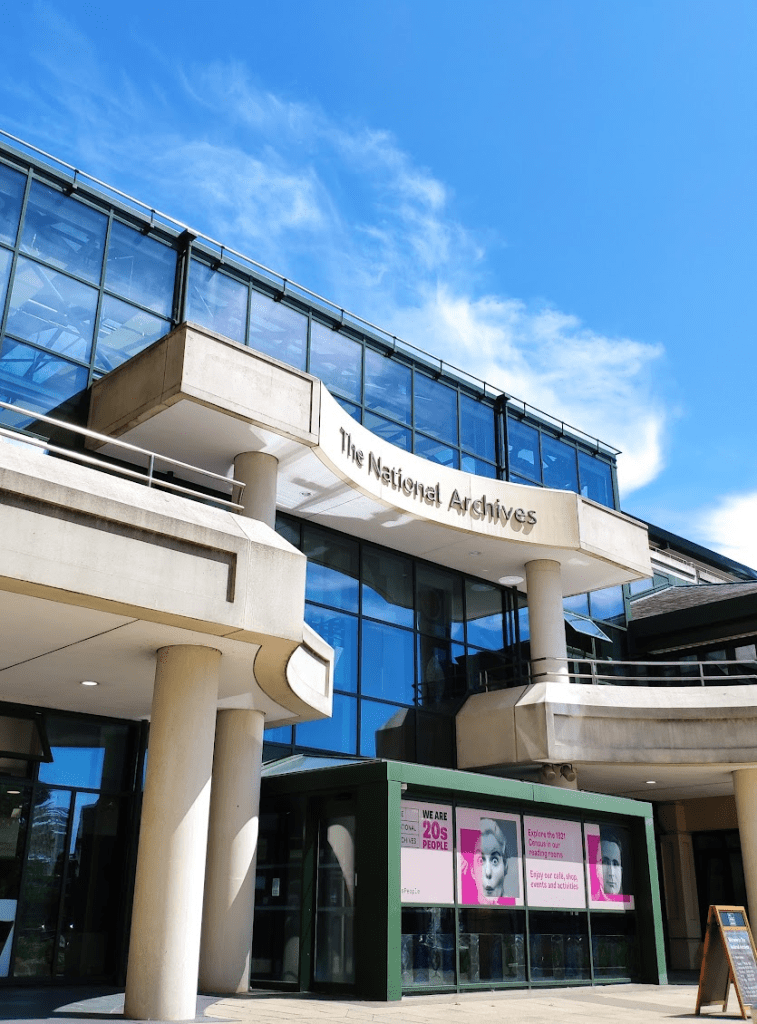

Inside The National Archives (TNA) is a glass box. A reader entering this special area of the reading room must don blue plastic gloves, then locate their requested items from inside a box. Once the reader has finished, they must wipe down surfaces and anything they touched, tick a form to indicate they have finished, reseal the item inside its box and return it to the shelf. Amongst the series that must be handled in this way, due to possible insecticide contamination, is the infamous FCO 141.[1]

In 2011, the British Government was forced to admit a secret. It had for decades been holding onto tens of thousands of files created by former colonial administrations that had been shipped to London on the eve of British withdrawal from their colonies. These records were subsequently released to TNA, where they formed FCO 141. A windfall for those interested in the colonies to which they pertained, the series also inspired research into how records were handled towards the end of the British Empire. Although colonial officials had considerable volition over how they affected withdrawal, a shared commitment to protecting the legacy of the Empire meant that many treated the files they had created in similar ways. As such, recent research has revealed that outgoing officials often destroyed or doctored countless files in an effort to uphold the Empire’s glorious image: a project that became known as ‘Operation Legacy’.[2]

One former British colony has, however, remained absent from the literature: Hong Kong. In a recent paper, I addressed this gap by piecing together the past, present and future of colonial records that were moved from Hong Kong to the UK.[3] In this post, I summarise the main findings of my paper by comparing the Hong Kong case with that of other British colonies and arguing that the handling of Hong Kong colonial government records was unique and largely escaped Operation Legacy.

The migrated archives

Across the rest of the British Empire, colonial records were handled in one of three ways: they were destroyed, left in place sometimes having been altered significantly, or removed to the UK. The vast majority of records befell the first fate: files went up in flames in India, Malayan records were incinerated en masse, records created in Uganda were cast into Lake Victoria and papers produced in Sarawak were dumped into the South China Sea.[4] Untold numbers of records were irretrievably lost in this orgy of destruction. Those that escaped burning or drowning were sometimes changed to edit out unedifying aspects of the Empire’s past then handed successor governments. Outgoing officials in Guiana, Malta and South Africa, for instance, were tacitly encouraged by the Colonial Office to remove particular papers from folders while officials in North Borneo checked correspondence for content that needed to be removed.[5] Outgoing officials were concerned above all else with avoiding embarrassment and upholding the Empire’s image. Weeding, destroying or removing evidence that might besmirch Britain and the memory of its Empire became known as ‘Operation Legacy’.[6]

A third ways that records were handled was removal, or ‘migration’, to the UK. Some 20,000 files originating in 40 former colonies made their way to the metropole before being rehoused at Hanslope Park, a Foreign Office facility outside of Milton Keynes.[7] There, they languished in legal limbo as officials failed to agree who was responsible for the records.[8] Over many years, the British Government repeatedly denied that it held these records until a court case forced the Foreign Office to admit what it was holding.

Once the records were opened as FCO 141, the controversy continued with debates that continue today over the rightful place of these collections. Many former colonies demanded the repatriation of these records.[9] Some sent teams to British institutions or paid for copies of files pertaining to the colonial past: Singapore purchased copies of records from the UK for use locally; the National Archives of India gathered material from the British Library; a team from Kenya microfilmed material and gathered artefacts to be returned.[10]

Throughout the process of destruction, alteration, removal and denial, the British Government’s secret had a racial aspect. Many administrations ensured that only white officials could know about and participate in the process of sorting and obliterating certain types of record. Colonies learned from each other how to segregate files by colour: one group of files could be handled by local people but another group could only be dealt with by (white) expatriate officers. Consequently, thousands of (white) former colonial officials must have known about what had happened to the records. Moreover, while Hanslope Park was and remains generally closed to the general public, over the years the occasional historian has inveigled access. From first to last, knowledge of the existence of these records was circulated amongst a privileged few and kept from those to whom they mattered most.[11]

The Hong Kong case

As I detail in my recent paper, however, the Hong Kong case escapes almost all of these themes commonly found across British colonies. Hong Kong had been colonised by the British in the 19th Century, the territory gradually growing through two treaties and a lease. The lease, which covered the largest area of Hong Kong, was set to expire in 1997. So, in the early 1980s, Britain and Beijing entered into negotiations resolving that Britain would hand Hong Kong to Beijing in 1997. The transitional period lasted more than a decade, during which time colonial officials discussed what to do about the records their administration had created.

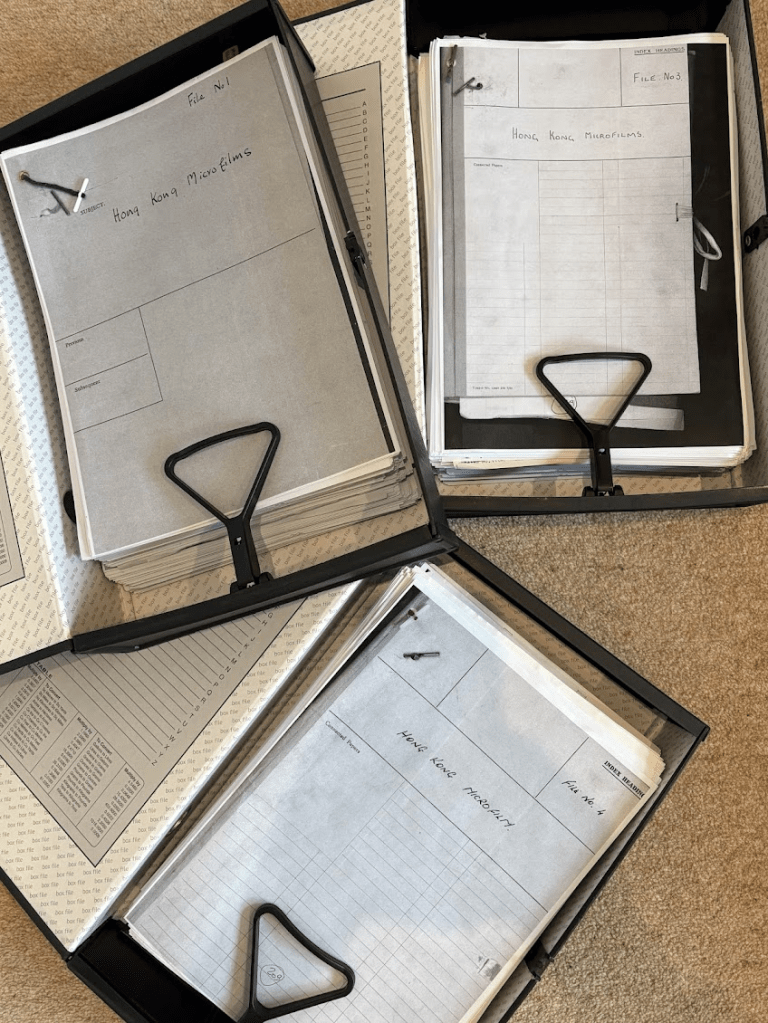

Hong Kong’s Governor Sir Edward Youde presaged that London would require a set of files to inform Britain’s relations with Hong Kong after 1997.[12] The Government Records Co-ordination Unit was promptly established to copy onto microfiche files for the future benefit of the British Government.[13] The Unit copied 27,000 files from across the secretariat.[14] Most were “classified”, meaning they were graded between “restricted” on the lower end to “top secret” on the higher end.[15] These copies were joined by around 5,500 original paper records, classified “secret and top secret”.[16] These two groups joined around 55,000 microfilmed files that had been sent from Hong Kong to the UK since the 1950s for safekeeping.[17] In total, some 88,000 files from the Hong Kong colonial government came to be housed at Hanslope Park.

Ahead of Britain handing Hong Kong to Beijing in 1997, officials negotiated the future of the Hong Kong colonial government archives. On 28 June 1997, the two sides signed the “Agreed Minute on Transfer of Archives” (档案移交协议), which allowed Britain to make duplicates of files for use in the UK, committed London to consulting Beijing in advance should it wish to make any of its copies public, and confirmed that the colonial government’s files would be passed to the post-1997 government.[18] Meanwhile in the UK, British officials sought legal grounds for retaining the Hong Kong collection.[19]

Comparing Hong Kong with other British colonies

There are few similarities between the treatment of Hong Kong’s records and those of other colonies. Firstly and most obviously, the Hong Kong records joined others in Hanslope Park. Secondly, the post-1997 Hong Kong government has also paid for copies of papers at TNA pertaining to the colonial past. From as early as 2018, Hong Kong’s Government Records Series began buying copies of certain series at TNA summing over 17,300 images purchased.[20] These two points are, however, where the similarities end.

In almost every regard, therefore, Hong Kong’s records were handled in an utterly different way to those of other British colonies. There is no evidence of mass destruction or alteration in the Hong Kong case. Embarrassment and reputation management was not the main motivator; instead, records were handled according to the practical need for London to have a suite of files after the handover. The vast majority of files moved to the UK were copies with almost all originals handed to the successor government. Additionally, there is no indication that race played a part in the Hong Kong case. Lastly, whereas collections from other colonies bewildered legal advisers in the UK, officials deliberated carefully and negotiated with their Chinese counterparts to seek a legal footing for the Hong Kong records.

The most notable difference is, of course, that the Hong Kong files remain closed whereas all other colonial collections are available as FCO 141 inside TNA’s glass box. Hong Kong’s colonial records survived the bonfires that characterised Operation Legacy yet remain closed. Whereas British officials across the empire shaped the historical record through flames and alterations, the British Government now wields its control by denying access to the Hong Kong collection in its care. The Hong Kong case shows that although FCO 141 is open at TNA, the effects of government control over the past endure.

Matthew Hurst is a PhD student at the University of York funded by the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities. His recent paper, ‘Hong Kong Colonial Government Migrated Archives at Hanslope Park’, was published open access in The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History and was awarded the British Association for Chinese Studies 2025 ECR Prize: https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2025.2561196

[1] Mandy Banton, “A ‘legacy of suspicion’: The UK National Archives, the ‘migrated archives’ and the insecticide debacle of 2022”, Africa Bibliography, Research and Documentation, vol. 2 (2023) DOI: 10.1017/abd.2023.5.

[2] Shohei Sato, “‘Operation Legacy’: Britain’s Destruction and Concealment of Colonial Records Worldwide”, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol. 45 no. 2 (2017) DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2017.1294256.

[3] Matthew Hurst, “Hong Kong Colonial Government Migrated Archives at Hanslope Park”, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History (2025) DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2025.2561196.

[4] Jordanna Bailkin, “Where Did the Empire Go? Archives and Decolonization in Britain”, The American Historical Review, vol. 120 no. 3 (2015) DOI: 10.1093/ahr/120.3.884; Mandy Banton, “Destroy? ‘Migrate’? Conceal? British Strategies for the Disposal of Sensitive Records of Colonial Administrations at Independence”, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol. 40 no. 2 (2012) DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2012.697622; Joel Hebert, “Dirty Documents and Illegible Signatures: Doctoring the Archive of British Imperialism and Decolonization”, Modern British History, vol. 35 no. 2 (2024) DOI: 10.1093/tcbh/hwae035.

[5] Hebert, op. cit.

[6] Sato, op. cit.

[7] Ian Cobain, The History Thieves: Secrets, Lies and the Shaping of a Modern Nation (Portobello Books, 2016).

[8] Timothy Lovering, “Expatriate Archives Revisited” in James Lowry (ed.), Displaced Archives (Routledge, 2017) DOI: 10.4324/9781315577609.

[9] Vincent Hiribarren, “Hiding the Colonial Past? A Comparison of European Archival Policies” in James Lowry (ed.), Displaced Archives (Routledge, 2017) DOI: 10.4324/9781315577609; Nathan Mnjama, “Migrated Archives: The Unfinished Business”, Alternation – Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa, vol. 36 (2020) DOI: 10.29086/2519-5476/2020/sp36a15.

[10] Sana Aziz, “National Archives of India: The Colonisation of Knowledge and Politics of Preservation”, Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 52 no. 50 (2017) JSTOR stable: 45132597; Nathan Mnjama, “Archives and Records Management in Kenya: Problems and Prospects”, Records Management Journal, vol. 13 no. 2 (2003).

[11] Tim Livsey, “Open Secrets: The British ‘Migrated Archives’, Colonial History, and Postcolonial History”, History Workshop Journal, vol. 91 no. 1 (2022) DOI: 10.1093/hwj/dbac002.

[12] Letter, Youde to Whitehead, 1 March 1985, TNA FCO 40/1914 f12.

[13] Yvonne Lai, “Don Brech; The former government archivist tells Yvonne Lai why Hong Kong needs legislation to protect its previous records”, South China Morning Post, 10 July 2011, 13.

[14] FCDO, “FCDO archive inventory”, 12 March 2025, accessed 14 April 2025 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/fcdo-archive-inventory.

[15] Letter, Brech to Barnes, 12 April 1988, TNA FCO 40/2608 f28.

[16] David Akers-Jones interviewed by Steve Tsang, 1990, Bodleian Special Collections MSS. Ind. Ocn. s. 416, 394.

[17] Savingram, Grantham to Creech Jones, 25 July 1949, FCDO Archive Inventory ref. 105 f1 obtained from the FCDO under the Freedom of Information Act (ref. FOI2024/21046).

[18] “Transfer of archives finally agreed”, South China Morning Post, 29 June 1997, 4.

[19] TNA released an illuminating collection of papers on this in response to a Freedom of Information request, archived here: https://web.archive.org/web/20170904210727/http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/about/freedom-of-information/information-requests/fco-non-standard-files-and-documents/.

[20] Disclosed by TNA in response to my Freedom of Information request (ref. CAS-229614-V3Y3W4).

You must be logged in to post a comment.