Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Author: CIGH Exeter

‘I Don’t Think I’m Wrong About Stalin’: Churchill’s Strategic And Diplomatic Assumptions At Yalta

Cross-posted from History Matters

On 23 February 1945 Churchill invited all ministers outside the War Cabinet to his room at the House of Commons to hear his account of the Yalta conference and the one at Malta that had preceded it. The Labour minister Hugh Dalton recorded in his diary that “The PM spoke very warmly of Stalin. He was sure […] that as long as Stalin lasted, Anglo-Russian friendship could be maintained.” Churchill added: “Poor Neville Chamberlain believed he could trust with Hitler. He was wrong. But I don’t think I’m wrong about Stalin.”[1]

Just five days later, however, Churchill’s trusted private secretary John Colville noted the arrival of:

“sinister telegrams from Roumania showing that the Russians are intimidating the King and Government […] with all the techniques familiar to students of the Comintern. […] When the PM came back [from dining at Buckingham Palace] […] he said he feared he could do nothing. Russia had let us go our way in Greece; she would insist on imposing her will in Roumania and Bulgaria. But as regards Poland we would have our say. As we went to bed, after 2.00 a.m. the PM said to me, ‘I have not the slightest intention of being cheated over Poland, not even if we go to the verge of war with Russia.”[2]

At an initial glance, there seems to be a powerful contradiction between these different sets of remarks. In the first, Churchill appears remarkably naïve and foolish, putting his faith in his personal relationship with a man whom he knew to be a mass murderer. In the second he seems strikingly, even recklessly bellicose, contemplating a new war with the Soviets, his present allies, even before the Germans and the Japanese had been defeated.

Surprising though it may seem, the disjuncture is not as large as it appears on the surface. Relations with the USSR and the future of Poland were not the only things that were at stake at Yalta. The Big Three took important decisions regarding the proposed United Nations Organization, and the post-war treatment of Germany, and even Anglo-US relations were not uncomplicated. In this post, however, I want to focus on the Polish issue and the broader question of how Churchill viewed the Soviet Union and its place in international relations more generally. I will outline three key assumptions that governed Churchill’s approach and which explain the apparent discrepancies in his remarks upon his return. Continue reading “‘I Don’t Think I’m Wrong About Stalin’: Churchill’s Strategic And Diplomatic Assumptions At Yalta”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

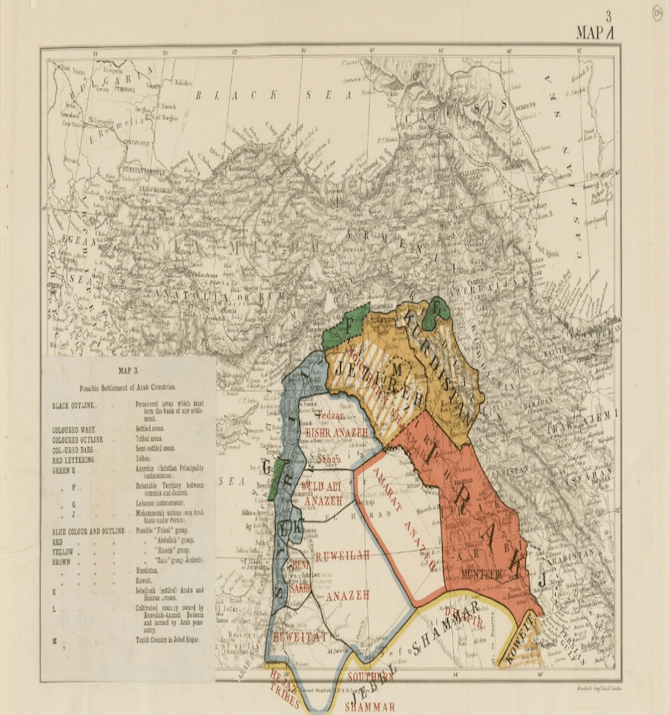

From an independent Kurdistan to when fascism almost came to Australia, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

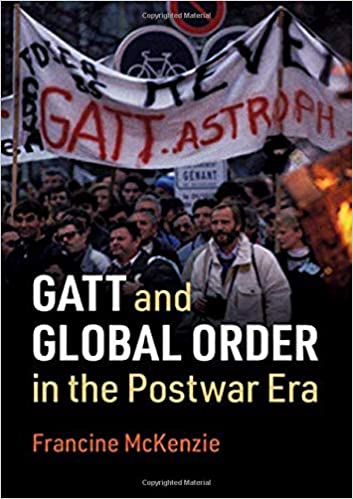

The History of GATT and the Current Crises in the Global Order

Francine McKenzie

Western University

Critics of the leadership and competence of the World Health Organization (WHO) during the Covid-19 pandemic have called for the fundamental reform of the organization. Before the pandemic, the dispute resolution body of the World Trade Organization (WTO) was under fire because its rulings were seen as unsound and over-reaching. These are serious criticisms, but they are not new.

All the major organizations in the UN-system have faced criticism and disgruntled members have periodically withheld funding, blocked proceedings, and threatened to quit. Occasionally they have even followed through. The latest round of criticism raises doubts about whether these organizations can survive in their present form. Before we can assess the shortcomings of these international organizations or evaluate the effectiveness of proposals to reform them, we need to better understand their failures. The history of one organization, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the WTO’s predecessor, can help us understand why the international organizations that are integral to the current global order invariably irritate members and disappoint expectations.

A lot has been written about GATT by political scientists, legal scholars, economists, historians, as well as officials and activists. But the organization itself is not well understood. Part of the confusion stems from the volume that has been written about GATT, much of it inconsistent or even contradictory. GATT has been described as a regime, a contract, an inter-governmental treaty, a body of law, a club, a forum, and a consumers’ union. It has been characterized as apolitical, technical, obscure, informal, and ineffective. These definitions and descriptors are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but they obscure the organization’s nature and operations. Contradictory assessments of its work and impact compound the problem. Some have criticized GATT as an instrument of American imperialism, an enemy of the environment, a levelling force that erases local cultures and national distinctiveness, and the cause of unemployment and individual suffering. But others claim it is ‘widely considered to have been one of the most successful – if not the most successful – of the postwar international economic organizations’[1] and ‘perhaps the most important and authoritative of all the current International Organizations and regimes’.[2]

Studies of GATT typically examine one of the eight rounds of trade negotiations conducted between 1947 and 1994. There’s a good reason behind this common approach. Negotiations that lowered tariffs, and later on other kinds of barriers to trade, advanced the organization’s mandate to liberalize and increase international trade. In GATT and Global Order in the Postwar Era, I shift the focus to quotidian and behind-the-scenes institutional activities that expand our understanding of how the organization functioned and the relationship between member states and the secretariat. I also focus on the Cold War, the rise of regional trade blocs, development and agriculture to explore the ways in which trade and politics were interconnected and show how GATT itself was ‘entangled in politics’.[3] Digging deeply into the institutional history revises our understanding of the nature and workings of our current global order. Continue reading “The History of GATT and the Current Crises in the Global Order”

Call for Papers – Special Issue of Punishment & Society: African Penal Histories in Global Perspective

In the twenty years since the publication of Florence Bernault’s edited volume A History of Prison and Confinement in Africa, the study of Africa’s penal systems has expanded tremendously. This scholarship has not only provided a clearer picture of penal ideas and institutions on the African continent across multiple time periods and locations, it has also offered insights into wider questions about the relationship between punishment, colonialism, and decolonization as well as the global circulation of penal techniques. This special issue aims to analyze African developments on their own terms and in relation to imperial and global narratives of punishment and penological networks as well as to integrate the fields of history, sociology, and criminology more closely, highlighting how theoretical insights of sociology and criminology can inform historical research. By presenting multiple works together in a special issue, we seek to emphasize the value of Africanist historical approaches and methods for interdisciplinary or multi-disciplinary research, and to highlight the contribution that studies of African penal systems can make to advancing understanding of global trends in punishment, showing how research on punishment in Africa not only engages with theories from the Global North, but also generates theories that reshape wider approaches to the study of punishment.

Topics for consideration could include (but are not restricted to): indigenous forms of punishment; colonial and postcolonial prisons; capital and corporal punishment; political imprisonment; forced labour; and detention camps.

We are interested in articles undertaking detailed case-study analysis of key historical trends, showcasing different methodological and disciplinary approaches. We invite submissions on all regions of Africa, and its relations with broader global or international developments in punishment and penology.

We particularly welcome submissions from scholars based in Africa and early career scholars. Continue reading “Call for Papers – Special Issue of Punishment & Society: African Penal Histories in Global Perspective”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From the long history of Black feminism in Europe to what’s in a “special relationship,” here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From fighting for the memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to how we remember in the twenty-first century, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history.

Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From remembering Claudia Jones to Brexit, Australian style, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

Historians Call for a Review of UK’s Home Office Citizenship and Settlement Test

21 July 2020

Cross-posted from the Historical Association

We are historians of Britain and the British Empire and writing in protest at the on-going misrepresentation of slavery and Empire in the “Life in the UK Test”, which is a requirement for applicants for citizenship or settlement (“indefinite leave to remain”) in the United Kingdom. The official handbook published by the Home Office is fundamentally misleading and in places demonstrably false. For example, it states that ‘While slavery was illegal within Britain itself, by the 18th century it was a fully established overseas industry’ (p.42). In fact, whether slavery was legal or illegal within Britain was a matter of debate in the eighteenth century, and many people were held as slaves. The handbook is full of dates and numbers but does not give the number of people transported as slaves on British ships (over 3 million); nor does it mention that any of them died. It also states that ‘by the second part of the 20th century, there was, for the most part, an orderly transition from Empire to Commonwealth, with countries being granted their independence’ (p.51). In fact, decolonisation was not an ‘orderly’ but an often violent process, not only in India but also in the many so-called “emergencies” such as the Mau-Mau Uprising in Kenya (1952-1960). We call for an immediate official review of the history chapter.

People in the colonies and people of colour in the UK are nowhere actors in this official history. The handbook promotes the misleading view that the Empire came to an end simply because the British decided it was the right thing to do. Similarly, the abolition of slavery is treated as a British achievement, in which enslaved people themselves played no part. The book is equally silent about colonial protests, uprisings and independence movements. Applicants are expected to learn about more than two hundred individuals. The only individual of colonial origin named in the book is Sake Dean Mohamet who co-founded England’s first curry house in 1810. The pages on the British Empire end with a celebration of Rudyard Kipling. Continue reading “Historians Call for a Review of UK’s Home Office Citizenship and Settlement Test”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From murder on the Middle Passage to doubling the time people lived in the Americas, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

The ‘Palace Papers’ and Australian Meddling in British Politics

John C. Mitcham

Duquesne University

Last Tuesday, the National Archives of Australia finally released the classified “Palace Letters” between the British Monarchy and Governor General Sir John Kerr. The highly anticipated correspondence shed new light on the famous 1975 Constitutional Crisis in Australia, when Kerr employed the reserve powers of the Crown to dismiss Gough Whitlam’s Labor Government. This was a pivotal moment in Commonwealth relations, sparking a diplomatic backlash from Canberra and fueling the movement for an Australian republic.

The constitutional evolution of Australia’s place within the Commonwealth stems from a historic and obsessive desire to protect national autonomy from British overreach. Indeed, the dusty annals of the old Colonial Office is replete with similar instances of British Cabinet ministers or Governors General interfering in the purely domestic affairs of the self-governing Dominions.

However, this trend could be a two-way street.

Nearly sixty years before the Whitlam dismissal, an Australian Labor leader helped to bring down a British Government. At the height of the First World War, Australian Prime Minister William Morris Hughes visited the United Kingdom for high-level consultations. The enigmatic Hughes quickly became a celebrity, rubbing elbows with the royal family and being feted by the press as the savior of the nation. Before long, he became a bit player in the famous palace intrigue against Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith. Continue reading “The ‘Palace Papers’ and Australian Meddling in British Politics”

As Leopold II statues fall, how do we ‘educate ourselves’ about his colony?

Robert Burroughs (Leeds Beckett University) and Sarah de Mul (Open University, the Netherlands)

Leopold Must Fall. The words become reality. In Belgium, officials are removing public statues of Leopold II in response to anti-racism protests.

Leopold II deserves notoriety. Between 1885 and 1908 he presided over a colonial regime in which mass murder and atrocities became routine. The impact of his destructive rule of the Congo Free State, today’s Democratic Republic of Congo, is profound.

The dismantling of public shrines is of course part of a wider movement sparked by the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020. Across much of the world, protestors are challenging racism by seeking removal of public monuments and street names honouring slave traders and colonial officials. Their actions are creating change. There have been repeated calls for the public to ‘educate ourselves’ on the histories of slavery, imperialism, and racism. Colonial history is now compulsory teaching in secondary schools in the Dutch-speaking region of Flanders, for example, and other national curricula will follow. Continue reading “As Leopold II statues fall, how do we ‘educate ourselves’ about his colony?”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From Imperial Japan and the Russian Revolution to reading some effing Orwell in the empire, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From how European empires broke their opium habit to the humbling of the Anglo-American world, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

Decolonising the curriculum: A conversation

Nandini Chatterjee and Richard Toye

University of Exeter

Nandini Chatterjee (NC): Is there a necessary connection between trying to make the university an inclusive place, and decolonising the curriculum?

Richard Toye (RT): Yes, I think there is, but at the same time they are not one and the same thing. That is to say, you could, in theory, have a wonderful, fully decolonised curriculum and at the same time fail to eradicate the various forms of discrimination that staff and students face. On the other hand, you could perhaps do a fair bit to removing those inequalities without having succeeded in adjusting the curriculum. But I do think that the two things go hand in hand, insofar as the messages that we give in the classroom are obviously a very important part of the university experience. If we set the right tone there, both in terms of inclusiveness and intellectual content, that really ought to have some wider benefit. I think there is a dilemma, though. Some people may well have an interest in a particular type of history because of their own ethnic and family history, and why not? But I think that we have to be careful not to assume that because somebody comes from a particular background they will be interested in a particular type or part of history and that ‘inclusiveness’ is achieved by laying on that variety of history. Black people may be especially interested in black history, for all sorts of good reasons, but nobody should expect them to be, or assume that they will be uninterested in other kinds of history. We wouldn’t expect white people only to be interested in white history, in fact I think we would look upon that as positively dangerous. What is your view? Continue reading “Decolonising the curriculum: A conversation”

You must be logged in to post a comment.