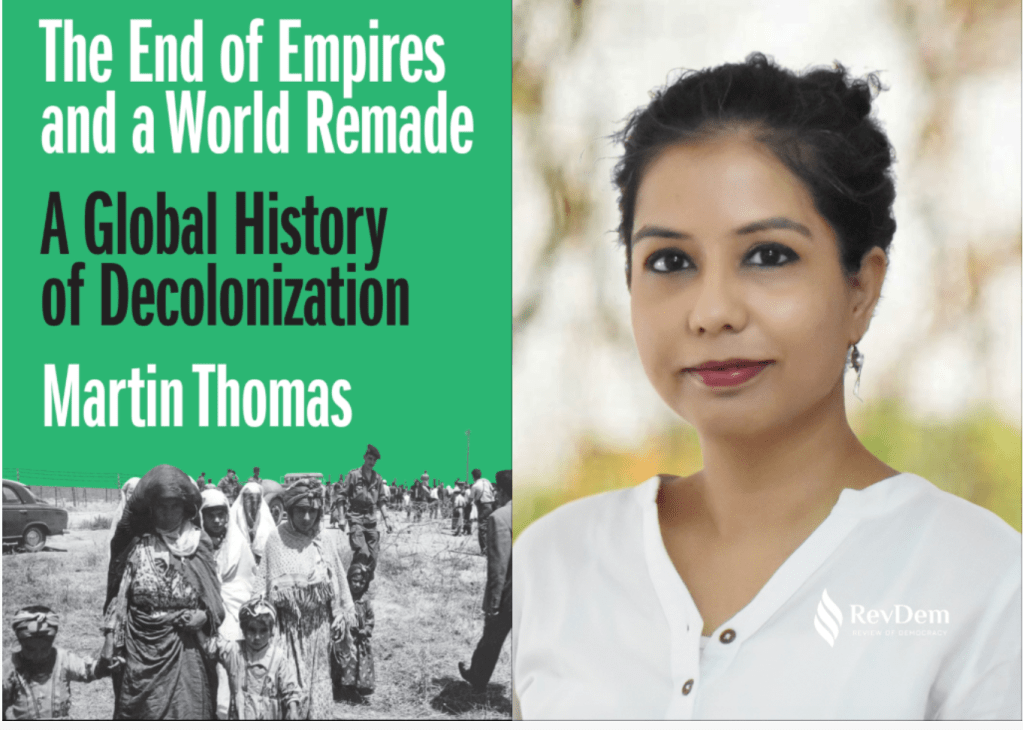

Dr. Anubha Anushree

Editor at the Review of Democracy

Cross-posted from the Review of Democracy

Dr. Anubha Anushree reviews Martin Thomas’s The End of Empires and the World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization, Princeton University Press, NJ, March 2024, 608 pages.

The title of Martin Thomas’s The End of Empires and a World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization signals the ambitious and unconventional nature of his now widely acclaimed project. From the outset, Thomas frames decolonization not simply as a linear dismantling of empires, but as a complex and often contradictory process—one that simultaneously disintegrated old hierarchies and gave rise to new, and sometimes equally exclusionary, national orders. His emphasis on decolonization as a reintegrative force highlights how the collapse of imperial structures often yielded unstable, improvised formations of authority and belonging. The process was deeply entangled with the rise of nationalism and the promise of democracy—two forces that could be emancipatory but also repressive, generative yet limiting. Offering a global history of decolonization is no small task—it requires navigating this terrain of ambivalence, where the struggle for freedom often reproduced new forms of domination, and where the language of democracy could both expand and foreclose political possibilities.

What distinguishes Thomas’s book is precisely this encyclopaedic ambition to capture decolonization in its mutating forms across various parts of the world. Spanning a vast geographical terrain and the turbulent decades between the 1940s and 1990s, the book begins with a striking anecdote: the celebration of Kenyan independence in Nairobi on December 11, 1963. Seen through the eyes of Labour MP Barbara Castle, a vocal advocate for Kenyan independence in the British Parliament, the scene encapsulates the contradictions of decolonization. A regimental band plays Auld Lang Syne, evoking the solemn grace of British ceremonial tradition, even as Castle herself arrives late, scrambling over a fence and tearing her dress in the process. This chaotic juxtaposition—the orchestrated rituals of empire alongside the messy reality of postcolonial transition—mirrors the broader argument of the book: decolonization was not simply the rejection of colonial rule but an unpredictable leap into nation-building, improvisation, and disorder.

Thomas’s study interrogates these contradictions by expanding the definition of decolonization. It is not merely, as he writes, “the concession of national self-determination to sovereign peoples” (13), but also a generative force that “energized different ideas of belonging and transnational connections” (4).

Continue reading “Unfinished Revolutions: Decolonization and Democracy in a Globalizing World”

You must be logged in to post a comment.