Shagnick Bhattacharya

University of Exeter

This article proposes that there were nuances and limits to Cold War-era British Prime Ministers’ use and abuse of the country’s imperial past to influence policy, shape national identity, and navigate international relations. That Prime Ministers’ use of public speeches to further their political agendas should receive greater academic attention was first proposed by Richard Toye[1] over a decade ago, and has currently taken the shape of an active research project[2] focussing specifically upon imperial rhetoric (titled ‘Talking Empire’—not to be confused with the CIGH’s podcast series!) led by Christian Damm Pedersen at the Syddansk Universitet, having recently received funding from the Carlsberg foundation.

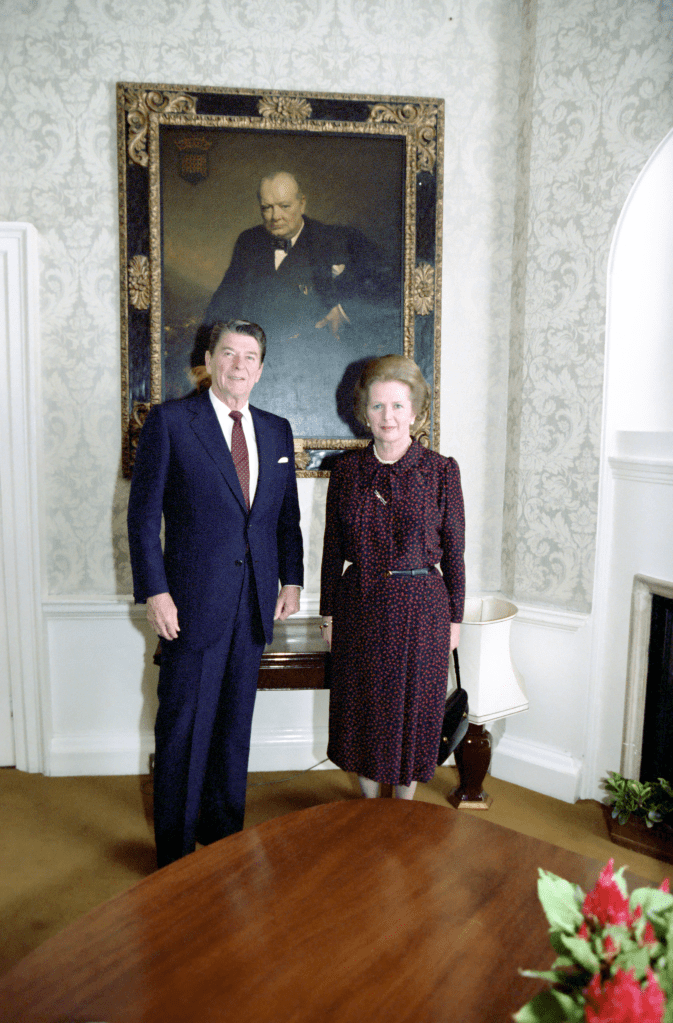

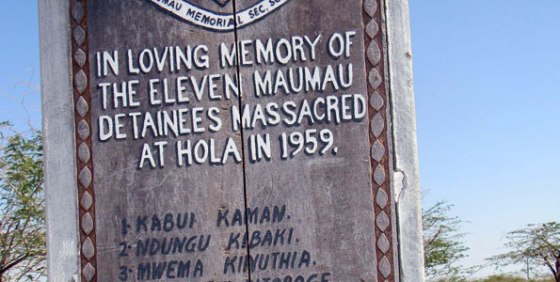

Using contemporary newspaper reports from across Britain as sources, my intervention here will be on two counts: firstly, by showing how Margaret Thatcher used the legacy and memory of Churchill in her rhetoric as a surrogate for referring to the imperial past (rather than directly mentioning the Empire in the first place) in order to publicly talk about her desired economic policies; secondly, by noting how any rhetorical premiership’s reliance on the imperial past could also be turned against the premier by their political opposition (and not even necessarily by anti-imperialists) in an attempt to strip it of its usefulness as a political resource for the former.

Continue reading “‘This country had a great empire’: The Nuances and Limits of the Rhetorical Premiership in Using the Imperial Past”

You must be logged in to post a comment.