Adam Nadeau

Among the more poignant observations made during the early days of overhaul of the United States federal government by President Donald Trump, his former senior advisor Elon Musk, and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) were a series of essays from Mike Brock’s Substack, Notes from the Circus. A former executive at Block Inc. who was involved in, among other things, building Cash App, Brock combines his insight into the world of big tech with his longstanding interest in philosophy to provide commentary on the current state of American democracy.[1] In one particularly illuminating post, Brock traces DOGE’s intellectual origins in part to a school of thought in Silicon Valley which holds that recent innovations in technology have rendered liberal democracy obsolete and that it is inevitable that Western democratic systems of government are to be superseded by digitally mediated, algorithmically optimized, corporatist technocratic autocracies.[2]

One might certainly agree with Brock that the pairing of corporate-technocratic power with the emergence of more advanced artificial intelligence threatens qualitatively unprecedented levels of social control and the attendant erasure of deliberative democratic processes.[3] However, it’s important to note that the blending of corporate entities and American political institutions is hardly a novelty of the twenty-first century. The fusion of private interest and civil governmental structures, particularly executive office, has been an integral part of the American political experiment dating back to the colonial and revolutionary periods, when private ventures backed by civil officeholders were the primary mechanisms for expanding colonial settlement, often with devastating effects on North American Indigenous populations.

Brock is correct to identify colonial opposition to the concentration of corporate power and state authority in the British East India Company (EIC) as one of the causal factors in the American Revolution.[4] However, his analysis misses the critical element that American revolutionary leaders were so strongly opposed to EIC activities in the thirteen colonies specifically because the Company represented a concentration of corporate power and state authority that was external to the colonies: the Tea Act of 1773 enforced a Company monopoly on tea in America that was meant to undersell tea on the colonial black market.[5]

Work by Philip Lawson, H. V. Bowen, P. J. Marshall, Robert Travers, Jonathan Eacott, Christian Burset, and others has increasingly demonstrated the social, economic, administrative, and legal interconnectedness between Britain’s Atlantic and Indian Ocean dominions during the colonial and revolutionary eras.[6] And Eacott especially has highlighted the significant effect of British imperial policies in India, particularly concerning commodities such as tea and textiles, on the development of American revolutionary ideology.[7]

Revolutionary leaders, meanwhile, took no similar issue with the discernable presence of private wealth in the nascent, domestic political institutions that guided their rebellion—when for instance, the western surveyor and land speculator George Washington was nominated as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, or when the merchant and president of the Continental Congress John Hancock, one of the wealthiest men in the colonies, affixed his signature to the Declaration of Independence. Indeed, Elizabeth Mancke identifies historical differentiation in polity formation between corporate and state directed projects as one of the main political divergences between those British North American colonies that became, respectively, the United States and Canada.[8]

In fact, the two colonies at the forefront of the revolutionary movement (and the home colonies of Washington and Hancock, respectively), Virginia and Massachusetts, were themselves founded as experiments in corporate-political government. On April 10, 1606, James I of England chartered two joint-stock companies to establish colonies on the east coast of the North American mainland.[9] The first company, which became known as the Virginia Company, was to settle between 34 and 41° north, while the second company, which became known as the Plymouth Company, was to settle between 38 and 45° north. Each colony was to be administered by a council in America that was subject to the overriding authority of a general council in England headed by a president or governor. The company financed the establishment of each colony and controlled all company land and resources. Early settlers were indentured servants in the company’s employment. The company raised capital through the sale of shares to private investors, known as “adventurers,” who expected a return on their investment as company stock increased in value following from settlement, agriculture, resource extraction, and commerce. Political leadership was often comprised of the wealthiest investors in the company; overlap in ownership with other contemporary joint-stock ventures, such as the EIC, was significant; and many governors never stepped foot in the colony.

Although the Plymouth colony initially failed, it was later reorganized into a distinct corporate body in 1620 under a new charter intending to revive colonial projects in New England.[10] New colonies in Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay were chartered in 1628–29,[11] existing as quasi-democratic, puritanical corporate theocracies within the jurisdiction of the gentry-dominated Council of New England until its charter was surrendered to the Crown in 1635.[12] The Massachusetts Bay Company charter continued to serve as the constitution of the colony until it was replaced by royal government when the Massachusetts and Plymouth colonies were amalgamated in 1691.[13] Virginia, meanwhile, transitioned from corporate to civil governance much earlier, when James I appointed a royal governor in 1624 and approved an elected assembly in 1627.

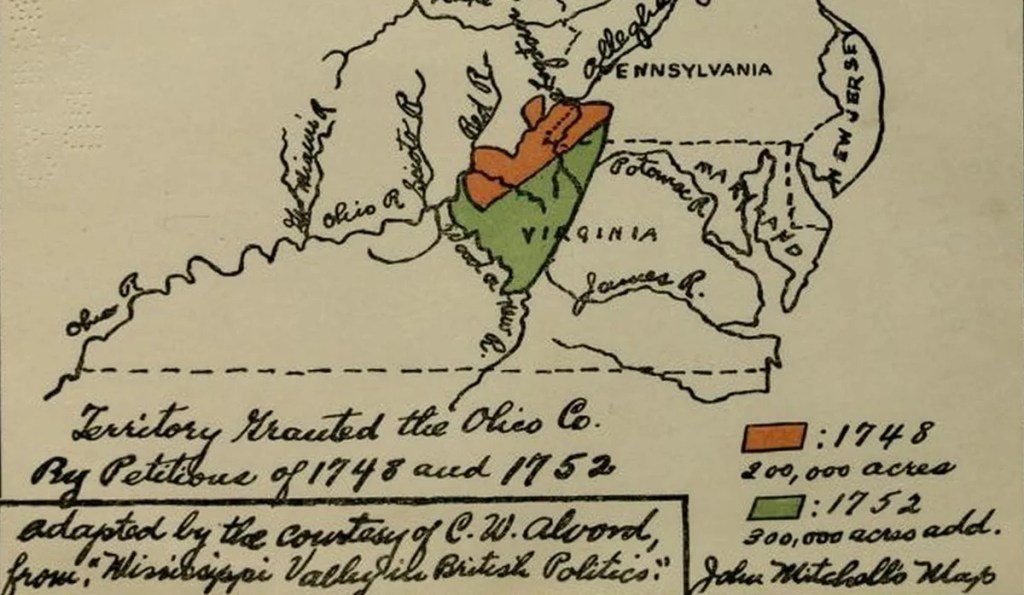

By the early eighteenth century, royal governments had largely replaced corporate entities as the preferred mode of colonial administration in English America. However, joint-stock ventures remained the primary instrument by which colonial interests launched settlement projects into new territories. After Virginia delegates negotiated with the Haudenosaunee for access west of the Appalachians in the Treaty of Lancaster in 1744,[14] a consortium of Virginia land speculators, including some of the wealthiest and most powerful figures in the colony, organized the Ohio Company of Virginia, which received a grant from the Board of Trade for 500,000 acres on the Ohio River in 1748 under the pretense that such lands were within Virginia’s dominion according to the colony’s second charter.[15]

When the commanding British officer at Fort Pitt, Henry Bouquet, blocked the company’s access to the Ohio Valley during the French and Indian War (1754–63) because the company’s grant was of questionable legality and threatened to destabilize diplomacy with Indigenous groups that were vital to the British war effort, company members attempted to bribe Bouquet with a share of 25,000 acres in the company’s grant.[16] Bouquet declined and issued an order prohibiting colonial settlement west of the Alleghenies.[17] When Indigenous groups conducted warfare across the trans-Appalachian west during the summer of 1763 in part due to the encroachment of colonial land companies like the Susquehanna Company of New England, which some believed governor Thomas Fitch of Connecticut was privately invested in,[18] the Pennsylvania trading company Levy, Trent and Co. distributed blankets from the smallpox hospital at Fort Pitt to visiting Lenape chiefs in an effort to spread disease on the frontier and weaken Indigenous groups’ capacity for war.[19]

Imperial restrictions on westward colonial expansion drew heavy criticism from American elites, many of whom led the revolutionary movement. Washington interpreted the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which acknowledged Indigenous land title and restricted colonial settlement west of the Appalachians, as a mere “temporary expedient to quiet the minds of the Indians.”[20] And the Quebec Act of 1774, which placed the territory between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers within the jurisdiction of the province of Quebec in part to deter settlement from the thirteen colonies, was cited by the Continental Congress as among Americans’ primary grievances in the lead up to independence.[21]

When war broke out in the colonies in 1775, one of Congress’ first military initiatives was an attempt to annex the province of Quebec in part to gain access to the continental interior. The American invasion failed the following year. However, in 1779, Congress launched a campaign on the New York frontier with the objective of, in Washington’s own words, “the total destruction and devastation” of the Haudenosaunee.[22] Additionally, as the war on the eastern seaboard began winding down after the Continental Army’s victory at Yorktown in October of 1781, Congress endorsed an escalation of hostilities in the Ohio country lasting well into 1782. Such campaigns were designed to destroy Indigenous communities and seize as much territory as possible prior to the settlement of a peace agreement between the United States and Britain in 1783.[23]

While the British Parliament passed a series of bills from the 1770s onwards intending to curb the concentration of power in the EIC and gradually transfer British administration in India from corporate to civil governance,[24] Washington, the chief executive of the fledging United States, became one of the largest landowners in America and was invited to serve as president of the Potomac River Company. Washington drew a salary from the company and worked to improve transportation links between the Potomac and Ohio rivers, an endeavour which, not coincidentally, increased the value of his landholdings at both Mount Vernon and in the west. Yet even Washington remained somewhat embarrassed by being gifted shares in the company, remarking that such “gratuitous gifts are made in other countries.” He accepted only on the basis that public works were in the national interest.[25]

Land companies continued to be the primary vehicle for launching projects for western settlement in the new American republic well into the nineteenth century. In 1797, the United States founder, senator, and prolific land speculator Robert Morris induced the Seneca to surrender title to roughly 3.5 million acres—nearly all their traditional homelands in Genesee River area in western New York—so that Morris could sell their lands to the Holland Land Company in an effort to dig himself out of crippling debt.[26] By the 1840s, more than a million settlers lived on the Haudenosaunee homelands of upstate New York.[27]

For an indentured labourer in at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1609; a British officer at Fort Pitt in 1760; a Lenape village chief in the Ohio country in 1763; or a Seneca warrior in western New York in 1797, the marriage of private interest and civil office in the 47th presidency would, in many ways, appear to be business as usual.

Adam Nadeau holds a PhD in History from the University of New Brunswick where his dissertation, “Inheriting Empire: Royal Proclamations, Parliamentary Legislation, and Imperial Integration in British North America and India, 1760–1793,” examined eighteenth-century transformations in British imperial governance in North America and South Asia and their effects on Crown–Indigenous relations, the emergence of American revolutionary ideology, the constitutional development of the binational Canadian settler-state, and the subsequent evolution of British imperialism in India and elsewhere.

[1] Mike Brock, “What the Hell Happened to Me (and to Silicon Valley),” Notes from the Circus, February 15, 2025, https://www.notesfromthecircus.com/p/what-the-hell-happened-to-me-and.

[2] Mike Brock, “The Plot Against America,” Notes from the Circus, February 8, 2025, https://www.notesfromthecircus.com/p/the-plot-against-america.

[3] Mike Brock, “The Final Despotism,” Notes from the Circus, February 17, 2025, https://www.notesfromthecircus.com/p/the-final-despotism.

[4] Mike Brock, “From Madison’s Vision to Musk’s Dystopia,” Notes from the Circus, February 22, 2025, https://www.notesfromthecircus.com/p/from-madisons-vision-to-musks-dystopia. See Peter D. G. Thomas, Tea Party to Independence: The Third Phase of the American Revolution, 1773–1776 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991).

[5] 13 Geo. 3, c. 44. See Benjamin Woods Labaree, The Boston Tea Party (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964).

[6] Philip Lawson, A Taste for Empire and Glory: Studies in British Overseas Expansion, 1600–1800 (London: Routledge, 1997); H. V. Bowen, “British Conceptions of Global Empire, 1756–83,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 26, no. 3 (1998): 1–27; P. J. Marshall, The Making and Unmaking of Empires: Britain, India, and America, c. 1750–1783 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Robert Travers, “Imperial Revolutions and Global Repercussions: South Asia and the World, c. 1750–1850,” in The Age of Revolutions in Global Context, c. 1760–1840, ed. David Armitage and Sanjay Subrahmanyam (London: Routledge, 2010), 144–66; H. V. Bowen, Elizabeth Mancke, and John G. Reid, eds., Britain’s Oceanic Empire: Atlantic and India Ocean Worlds, c. 1550–1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Jonathan Eacott, Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600–1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016); Christian R. Burset, An Empire of Laws: Legal Pluralism in British Colonial Policy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2023).

[7] Eacott, Selling Empire, ch. 4. For a detailed analysis of the considerations driving some of the key imperial policies intersecting Britain’s American and Indian dominions, see H. V. Bowen, Revenue and Reform: The Indian Problem in British Politics, 1757–1773 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

[8] See Elizabeth Mancke, The Fault Lines of Empire: Political Differentiation in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, ca. 1760–1830 (New York: Routledge, 2005); “Another British America: A Canadian Model for the Early Modern British Empire,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 25, no. 1 (1997): 1–36; and “Early Modern Imperial Governance and the Origins of Canadian Political Culture,” Canadian Journal of Political Science 32, no. 1 (1999): 3–20.

[9] First Charter of Virginia, April 10, 1606, The Avalon Project, Lilian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/va01.asp.

[10] Charter of New England, November 3, 1620, Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass01.asp.

[11] Charter of Massachusetts Bay, March 4, 1628, Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass03.asp; Charter of the Colony of New Plymouth, January 13, 1629, Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass02.asp.

[12] Act of Surrender of the Great Charter of New England to His Majesty, June 11, 1635, Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass04.asp.

[13] Charter of Massachusetts Bay, October 7, 1691, Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass07.asp.

[14] Treaty of Lancaster, 1744, Tribal Treaties Database, https://treaties.okstate.edu/treaties/treaty-of-lancaster-1744-21777.

[15] Kenneth P. Bailey, The Ohio Company of Virginia and the Westward Movement, 1748–1792: A Chapter in the History of the Colonial Frontier (Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark, 1939); Second Charter of Virginia, May 23, 1609, Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/va02.asp.

[16] Thomas Cresap to Henry Bouquet, July 24, 1760, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015070207587&seq=144; George Mercer to Henry Bouquet, December 27, 1760, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015070207587&seq=275.

[17] Henry Bouquet, Order, October 30, 1761, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106005503211&seq=203.

[18] James Hamilton to Jefferey Amherst, Oct. 17, 1762, The National Archives, WO 34/33, 347–48

[19] Levy, Trent and Company, Account against the Crown, August 13, 1763, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015070207843&seq=242&q1=levy. While the British commander-in-chief in North America, Jeffery Amherst, is regularly credited with conceiving of spreading smallpox to Indigenous groups around Fort Pitt in 1763 via infected blankets, both the documentary evidence and modern historical scholarship indicates that William Trent of Levy, Trent, and Co. actually sought to spread disease in this manner weeks before it was considered by Amherst in his correspondence to Bouquet. There is no evidence that Amherst and/or Bouquet ever acted on this idea. See Elizabeth A. Fenn, “Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst,” Journal of American History 87, no. 4 (2000): 1552–80; Philip Ranlet, “The British, the Indians, and Smallpox: What Actually Happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?” Pennsylvania History 67, no. 3 (2000): 427–41; and Patrick J. Kiger, “Did Colonists Give Infected Blankets to Native Americans as Biological Warfare?” History, November 15, 2018, https://www.history.com/articles/colonists-native-americans-smallpox-blankets.

[20] Royal Proclamation, October 7, 1763, Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/proc1763.asp; George Washington to William Crawford, September 17, 1767, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-08-02-0020.

[21] 14 Geo. 3, c. 83; John Adams, Notes of Debates in the Continental Congress, October 17, 1774, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Volume%3AAdams-01-02&s=1511311112&r=221; James Duane, Notes of Debates, October 17, 1774, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000001116021&seq=149. The Quebec Act was considered by American colonists as one of the Coercive/Intolerable Acts, a program of punitive legislation passed by the British Parliament in 1774 in response to the Boston Tea Party. See David Ammerman, In the Common Cause: American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974). However, the Quebec Act was under development well before the East India crisis of 1772–73 and was more so concerned with implementing a constitution for the province of Quebec and addressing questions surrounding Indigenous relations. See Philip Lawson, The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age of the American Revolution (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1989); and François Furstenberg and Ollivier Hubert, eds., Entangling the Quebec Act: Transnational Contexts, Meanings, and Legacies in North America and the British Empire (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020).

[22] George Washington to John Sullivan, May 31, 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Volume%3AWashington-03-20&s=1511311112&r=661.

[23] See Barbara Alice Mann, George Washington’s War on Native America (Westport, CT: Prager, 2005).

[24] Approximately eight bills were passed as part of this century-long process, beginning with the Regulating Act of 1773 (13 Geo. 3, c. 63) and concluding with the disestablishment of the EIC by the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act of 1873 (36 & 37 Vict., c. 17).

[25] See Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin, 2010), 501–3, 803; and Justin Fox, “George Washington had some business interests, too,” Commercial Appeal, November 25, 2016, https://www.commercialappeal.com/story/opinion/columnists/2016/11/25/george-washington-had-some-business-interests-too/94358980.

[26] Alan Taylor, The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 309–16.

[27] Mann, Washington’s War on Native America, 110.

You must be logged in to post a comment.