Hualing Zhai[1], Quinten Heymans[2], Bartolomeo Perazzoli[3], Sophie Paynter[4], Alice Wadsworth[5]

Students of ‘Linguistic Landscapes‘, Venice International University Summer School 2025

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven (Coordinator); Richard Toye, University of Exeter (Coordinator); Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Iuav, University of Venice; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

Introducing San Francesco della Vigna

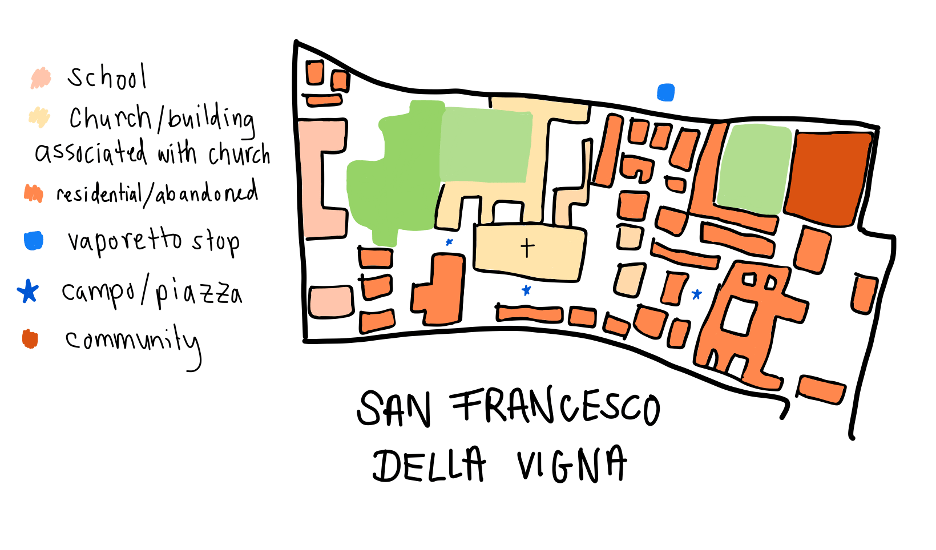

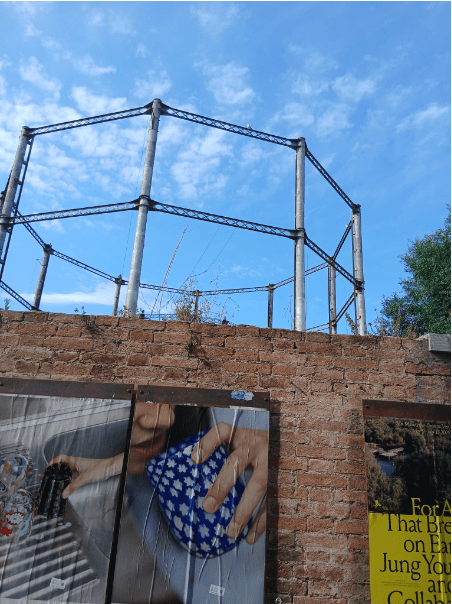

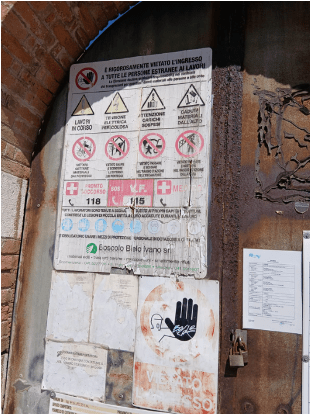

San Francesco della Vigna (later also SFdV), located on the northeastern edge of Venice, presents a sharp contrast to the city’s typical romantic image. The area may feel, in some ways, stuck in time, with the campo (the Venetian equivalent of a piazza) overlooked by a large gasholder (image 3) on one side, and the beautiful if somewhat imperious 16th-century church of San Francesco della Vigna (image 4). Our group, as part of the 2025 VIU Linguistic Landscapes summer school, explored this working-class neighbourhood focusing on the themes of presence and absence. At first, the area seems quiet and almost forgotten, with few signs of life such as shops, cafés, or passersby. However, through exploring the linguistic and semiotic landscapes and the soundscape of the area, we found a quietly strong local identity to be bubbling away beneath the seemingly barren surface.

We were lucky enough to explore every inch of the isola, and the walls were deep in conversation with the neighbourhood and with each other. So perhaps this work, and any work of mapping out a linguistic landscape, can be considered a kind of ethical ‘eavesdropping’. We observed- and listened- from outside but we were also able to conduct a few interviews as part of our research. Interviews with residents highlighted ongoing gentrification and local feelings of resistance. One construction worker noted that scaffolding usually indicates Airbnb renovations, reflecting economic and demographic changes.

Remainders of the past

As Venice has been inhabited for over 1,600 years, the city has seen a plethora of changes. However, this change is perhaps more visible in San Francesco della Vigna than in other surrounding neighbourhoods, due to the fact that the past remains tangible. Even though its appearance is less historical and more homogeneous due to the residential nature of the area, the past remains visible in the streets.

A major sign of San Francesco della Vigna’s new presence and how this affects its historical panorama can be seen in picture 1, an isolated standing gate in the middle of a calle. This gate used to be the entrance of a historical palazzo, Il Palazzo Sagredo, which has been demolished. An old house number (which has been painted over) can also be seen in the upper left corner of the gate; this shows that there has been an effort to fit in the remains of the palazzo into the current (administrative) order of the city.

The physical construction, nevertheless, still occupies a part of the street and causes a moment of de-automatisation in the street scene: all of a sudden, the broad calle is interrupted by an old gate leading to nowhere but the same street. As a passer-by, one can choose to walk through it or to just ignore it. Either way, the visual aspect of the isolated gate as a historical frame that allows the view on the more modern social living blocks shows the distinction between the history of the area and the housing problems, to which the buildings pretend to be a solution.

More Venetian, More Forgotten?

In a city often criticised for its overtourism, the neighbourhood of San Francesco della Vigna stands out as its linguistic and semiotic landscapes showcase a strong local identity. Stickers on the walls in Venetian abound, and their presence is accentuated by the absence of the kinds of Italian and international stickers placed in more central areas of Venice. Additionally, the names on the intercoms depict Venetian surnames; many end in the letter N, a common feature of Venetian surnames (Dolcetti, 2014). Furthermore, there is a palpable passion towards the local football team Venezia FC, as many stickers of support are present and a fanclub is a stone’s throw away. The area is decorated in the crest’s colours: orange and green, and the stadium is very close. These three aspects of the semiotic landscape are critical as they show that the area is frequented and inhabited mostly by locals. As such, the linguistic and semiotic landscape of San Francesco della Vigna is one of a perhaps anachronic but robust local Venetian neighborhood. Yet, one finds the official signage to be in bad condition, highlighting underinvestment by the municipality and perhaps an absence of the state. On the other hand, the church signage was often highly maintained, showcasing that perhaps in this Venetian neighbourhood which is in some ways stuck in time, the church is still present but the state has since left the area behind.

Walls in Conversation

You could be forgiven for thinking that San Francesco della Vigna was somewhat abandoned. Certainly from the photos we took, you might think that this was the case. While focusing on our themes of absence and presence, we decided that the absence of people in the streets required a more nuanced lens. Tourists do not abound, perhaps due to a relative lack of attractions compared to the rest of Venice (image 10) but only listen closely to the buildings and they will speak to you. The soundscape (Smith, 1994) of the area reflects its heavily residential character. Italian/Venetian of a casual nature (it was sometimes difficult for the untrained ear at a distance to discern between the two!) was spoken inside and we also identified sounds of cooking and the radio playing; all signs of lives being led within the neighbourhood.

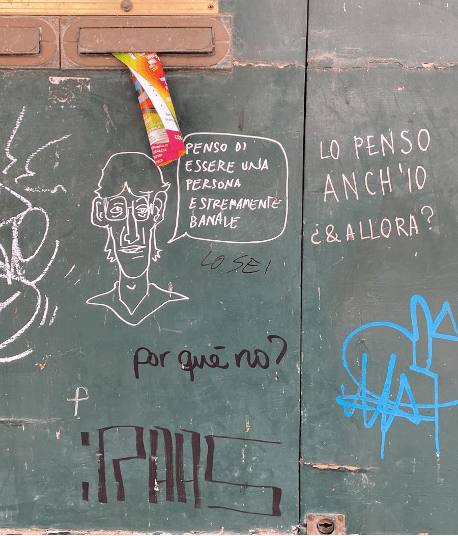

The walls also speak in other ways. While some graffiti needs decoding, there are some that are written clearly and in response to other graffiti. Picture 6 shows an example of a conversation had on the walls of San Francesco della Vigna. The imagined beginning of the conversation is the drawing of the person who says “I think I am an extremely boring person”. This is met with two messages in response: “you are” directly underneath and “I think so too. Now what?”. There is then below these three interlocutors a message in Spanish- “why not?” (although noticeably without the standard inverted question mark, required of questions in Spanish). Interestingly, the “Now what?” in the (imagined) third part of the conversation to the right does have this missing element of the inverted question mark, although this does not feature in standard written Italian. The presence of these conversations which possess bilingual awareness could indicate the presence of Spanish speakers in the area, but it is more likely that these references are due to the proximity of the Italian and Spanish languages and cultures.

Poetry on the Periphery

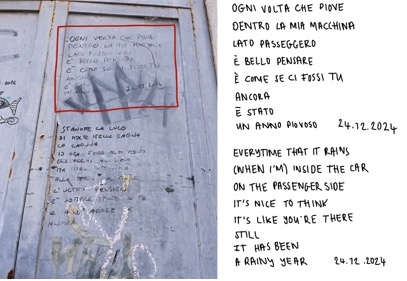

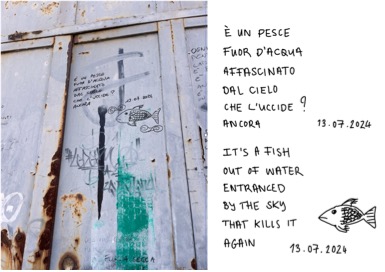

We discovered further compelling evidence of the presence of flourishing life in San Francesco della Vigna on an old metal door, where we encountered a series of handwritten poems. The consistent handwriting and tone of the poems suggests a single author. In this powerful form of linguistic expression, we can begin to understand how graffiti offers a voice to those in the margins, or in the case of San Francesco della Vigna a voice from the peripheries, which meaningfully contributes to the creative landscape of the area.

These poems are located on a high traffic calle of the area, on the way to the vaporetto stop, their location thus indicates a desire to be seen. At the same time, the quiet, almost abandoned feeling of the area, creates an illusion of a private space, where someone has chosen to write their personal thoughts. Some of the poems have begun to fade, which highlights their ephemeral nature. One day they will not be here at all, but this feels like a deliberate choice. The final poem is dated Christmas Eve 2024, suggesting the poets themselves have left the area, as their physical presence disappears, so too does their linguistic presence. In this way, the linguistic landscape reflects the fragile nature of presence in this area.

These poems not only affirm the presence of people in San Francesco della Vigna, but also demonstrate a very personal example of linguistic landscape. It is an individual reaching out, inviting others to appreciate their art, prompting a form of silent communication found in this peaceful zone of Venice.

Conclusion

This blog post intended to provide a brief overview of the linguistic landscape in the neighbourhood of San Francesco della Vigna, focusing on different aspects of absence and presence in this particular Venetian area. We noted during our fieldwork that this neighbourhood differs in multiple ways from the more well-known and touristic areas of the city. A striking example was the lone-standing gate of a building that was demolished for the benefit of social housing; history is absent and present at the same time. We also focused on the people living in this residential area and the ways in which we could trace them in the landscape. We were able to observe a high number of Venetian surnames on the intercoms, proving the presence of ‘real’ inhabitants rather than tourists. Furthermore, the stickers supporting the Venetian football club can be seen as a proof of local anchorage. Nevertheless, the walls do ‘talk’ in different languages: we found a small conversation in Italian and Spanish. Lastly, with poems found on a wall, we were able to get an insight into the private feelings of the author, who deliberately chose to disclose them in San Francesco della Vigna.

Bibliography

Dolcetti, G. (2014). Famiglie e cognomi veneti e friulani: Il libro d’argento delle famiglie nobili cittadine e popolari del Veneto (2 voll., brossura; F. B. De Nobili, Cur.) Dario De Bastiani Editore

Smith, S. J. (1994), ‘Soundscape’, Area, 26 (3), p.232–240.

Appendix

[1] zhl0627@hotmail.com

[2] quinten.heymans@student.kuleuven.be

[3] bartojochen@gmail.com

[4] sophiepaynter9@gmail.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.