Shagnick Bhattacharya

University of Exeter

This article proposes that there were nuances and limits to Cold War-era British Prime Ministers’ use and abuse of the country’s imperial past to influence policy, shape national identity, and navigate international relations. That Prime Ministers’ use of public speeches to further their political agendas should receive greater academic attention was first proposed by Richard Toye[1] over a decade ago, and has currently taken the shape of an active research project[2] focussing specifically upon imperial rhetoric (titled ‘Talking Empire’—not to be confused with the CIGH’s podcast series!) led by Christian Damm Pedersen at the Syddansk Universitet, having recently received funding from the Carlsberg foundation.

Using contemporary newspaper reports from across Britain as sources, my intervention here will be on two counts: firstly, by showing how Margaret Thatcher used the legacy and memory of Churchill in her rhetoric as a surrogate for referring to the imperial past (rather than directly mentioning the Empire in the first place) in order to publicly talk about her desired economic policies; secondly, by noting how any rhetorical premiership’s reliance on the imperial past could also be turned against the premier by their political opposition (and not even necessarily by anti-imperialists) in an attempt to strip it of its usefulness as a political resource for the former.

Simply put, the term ‘rhetorical premiership’ describes ‘the collection of methods by which prime ministers since 1945 have used public speech to augment their formal powers.’[3] That said, the use of imperial memory and rhetoric in modern British politics has been explored in a wide range of scholarship so far. Gilroy,[4] Schwarz,[5] and Ward[6] have all highlighted the enduring resonance of imperial ideas in shaping British identity long after decolonisation. Meanwhile, Webster[7] and Edgerton[8] have further interrogated how political figures drew upon—or sought to repress—the imperial past in narratives of modernisation and decline. Yet, most studies tend to focus either on cultural representations of empire or on broader ideological trends in British political discourse. Less attention has been paid to the specific rhetorical strategies of prime ministers during the Cold War, particularly the nuanced ways in which premiers like Thatcher invoked the imperial past indirectly, through association with predecessors or by adopting coded references, and the ways in which it could both add to and limit their powers depending upon their circumstances.

In 1983, at a Conservative Party conference in Scotland, Prime Minister Thatcher gave a public speech to all gathered on how she was intent upon following the policies of Sir Winston Churchill and expressed her hope to one day be compared with his premiership.[9] She emphasised how he believed ‘very firmly in the British Empire’ and that it was one of his ‘great’ qualities. But at that point in her speech, she diverged into talking about her own proposed economic policies, saying how Churchill ‘was a passionate believer’ in her ideas of private enterprise being a useful force for the creation of wealth. This was truly representative of Thatcher’s general rhetoric at the time, as among many others a political commentator writing to the Scotsman a year prior called her ‘a latter-day Churchill’.[10] Therefore, imperial rhetoric was not just necessarily present in talking about the Empire directly, but also about invoking the names and imitating the rhetoric of prominent former Prime Ministers who upheld the Empire in their own policies. It thus created a self-sustaining political cycle spanning generations across the Cold War of the imperial past legitimising the holders of executive power in the present.

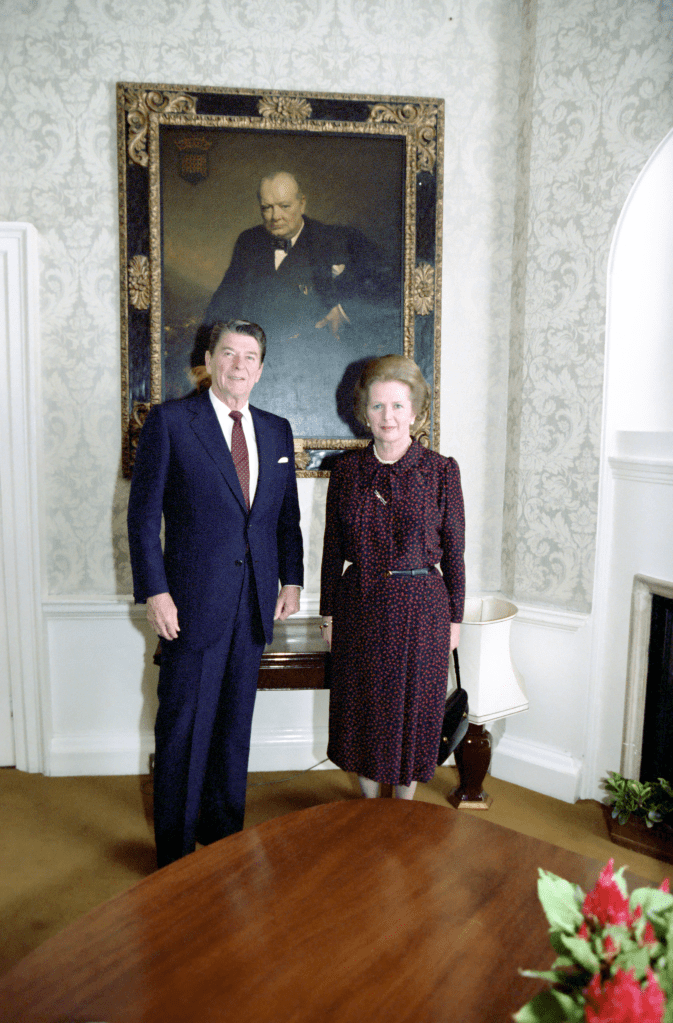

In fact, in another interaction in the form of an interview with the Daily Post in 1985, Thatcher used the same strategy to once again talk about her political ambitions and, using that as a focal point, her economic policies. She began by posing under a portrait of Churchill at 10 Downing Street, while expressing her desire to be in power for another decade.[11] From this she moved on to how Britain must start adjusting to its post-imperial identity: ‘We are not as business-minded as other nations. When we were building our Empire, we concentrated our academic talents on producing administrators. Now we have to concentrate on getting people into business.’ Interestingly, then, she used the image of Churchill to set the stage for communicating her political agenda when mentioning Empire directly would not have served her as well. When she does mention the Empire, conveniently forgetting the role of business interests like the East India Company in forging it, or the role of eighteenth-century economic ideals of mercantilism in sustaining it, she is able to do it without diminishing the usefulness of the rhetoric of the imperial past in re-making and re-imagining a version of Britain her speeches advocated for. The fact that rhetorical tactics like these did work in her political favour is quite evident, too. For example, even about two years before Thatcher became the Prime Minister a local woman from South Shields writing to the Newcastle Journal comments on her as being ‘the greatest personality this country has produced since Sir Winston Churchill’ before lamenting about the time when ‘this country had a great empire’ and how Britain would become ‘an infinitely better country with Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister.’[12]

However, such a strategy had its own pitfalls of the imperial rhetoric coming to equally be used against a Prime Minister’s policies whenever the opportunities arose. Hence, Thatcher’s stance of Euroscepticism and her foreign policy frequently drew criticism involving imperial rhetoric—like the Labour peer Baroness Blackstone’s 1989 statement ‘Mrs Thatcher continues to prance around on the world stage as if the country hadn’t lost its empire.’[13] Similarly, Macmillan’s foreign policy drew political opposition from groups like the ‘League of Empire Loyalists’ who proceeded to heckle him during his 1958 speech to a meeting of the Conservative Political Centre, shouting slogans such as ‘Keep Britain Free’ and ‘NATO makes Britain a satellite of the Yankees’.[14] Notably, later that year Macmillan ended up announcing the official rebranding of the ‘Empire Day’ to the ‘Commonwealth Day’, after proposals to do so at the highest levels of the government had existed at least since 1957.[15] Clearly, there were limits to how much the premier could use and abuse the Empire for their own political purposes, and it could also run reciprocally. Toye does briefly mention limitations on prime ministerial rhetoric due to constraints placed on which Prime Minister could say what at a given time—like Attlee’s inability to offer a speech similar to Churchill’s 1946 ‘iron curtain speech’ at the time—or in terms of a lack of political capital such as Blair’s inability to build sufficient public trust through his public speeches following the Iraq war.[16] My analysis here, though, deviates by looking outward onto the respective political worlds that Prime Ministers inhabited, delving instead into the subversion of their agency by the structures of their political opposition, or their political opposition influencing that agency. Imperial rhetoric was not just about national memory, but a contested resource in day-to-day power struggles.

Therefore, in conclusion, I think looking for nuances within as well as limitations whereof visible or hidden in public speeches of postcolonial British Prime Ministers would be one of the key ways we can better understand how the imperial past simultaneously could and could not be used and abused to advance the political aims of a ruling Prime Minister. Situated within a Cold War context, this would be an even more important exercise in truly getting a glimpse of how Britain itself (from the perspective of its highest political institution) was trying to reconcile between its imperial past and its postcolonial liberal democratic present.

Even though it was no longer a global hegemon, it is undeniable that prime ministers still wanted to project that image for their governments, parties, the media, and the voters. After all, there must be a reason why both the Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath and the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson publicly chose to oppose the renaming of the Order of the British Empire to a ‘more contemporary nomenclature’ when the issue was raised in the House of Commons—almost three years apart.[17] In their response, while Heath stated that there was ‘no great demand for a change,’ Wilson emphasised how the ‘balance of advantage remains’ given the level of recognition that the award represents. Two premiers on opposing ends of the political spectrum agreeing, for their own purposes, to keep the memory of the Empire alive—using two distinct arguments!

Bio: Shagnick “Nick” Bhattacharya is a recent graduate of the University of Exeter, where he completed his Master of Research in Economic and Social History with distinction. He is a historian of the British Empire on most days, but has also previously worked with local histories of late medieval and early modern Devon. He is currently an independent researcher handling multiple different projects in the hope that it may be just enough to turn the tide when it comes to applying again for doctoral funding.

[1] Richard Toye, “The Rhetorical Premiership: A New Perspective on Prime Ministerial Power Since 1945,” Parliamentary History, Vol. 30, pt. 2 (2011).

[2] See Talking Empire: Prime Ministerial Rhetoric and the Search for a Usable Past in Post-Imperial Britain: https://www.carlsbergfondet.dk/en/what-we-have-funded/cf24-1868/.

[3] Richard Toye, “The Rhetorical Premiership,” 175.

[4] Paul Gilroy, Postcolonial Melancholia (Columbia University Press, 2006).

[5] Bill Schwarz, Memories of Empire, Volume I: The White Man’s World (Oxford University Press, 2011).

[6] Stuart Ward, British Culture and the End of Empire (Manchester University Press, 2001).

[7] Wendy Webster, Englishness and Empire 1939–1965 (Oxford University Press, 2007).

[8] David Edgerton, The Rise and Fall of the British Nation: A Twentieth Century History (Allen Lane, 2018).

[9] “Maggie ‘following the policies of Churchill’,” Belfast News-Letter, 1 September 1983, 3.

[10] “Early warning to latter-day Churchill,” The Scotsman, 13 May 1982, 8.

[11] “Now for 10 years in power, says Maggie,” Liverpool Daily Post, 12 February 1985, 8.

[12] “After Churchill comes Thatcher,” Newcastle Journal, 11 April 1977, 6. Interestingly, the woman also laments about how ‘men have lost their masculinity and women their grit because men now must attend at the accouchment chamber’ since Britain lost its Empire. Definitely worth investigating further for any scholars of gender!

[13] “Prancing Thatcher,” Aberdeen Press and Journal, 26 January 1989, 13.

[14] “Premier is Heckled by Hampshire Loyalists,” Portsmouth Evening News, 13 March 1958, 16.

[15] “Proposal to change the name of Empire Day to Commonwealth Day,” PREM 11/2601, National Archives, Kew.

[16] Richard Toye, “Rhetorical Premiership,” 189-190.

[17] “Order of The British Empire,” House of Commons Sitting of 29 February 1972; and “British Empire Order,” House of Commons Sitting of 12 January 1976. Accessed through Hansard.

In memory of Ghee Bowman.

You must be logged in to post a comment.