Berizzi Mariachiara[1], Boam Olivia[2], Fourie Nicholas Charles[3], Pizarro Jacinto Laura[4], Yücel Dinç Fatma[5]

‘Linguistic Landscapes‘, Venice International University Summer School 2025

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven (Coordinator); Richard Toye, University of Exeter (Coordinator); Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Iuav, University of Venice; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

In Santa Marta, a quiet Venetian district, the city itself becomes a text: walls, streets, and public spaces speak through signs, graffiti, and infrastructures that reveal five interwoven themes: Anti-tourism, Transport & Mobility, Multilingualism & Symbolic Resistance, Government & Authority, and Prison as an Edge. From anti-tourism sentiments to the symbolic tensions of incarceration, our investigation examines how language, infrastructure, and public space interact to shape meaning and mobility. As shown in Figure 1, which provides a satellite view of Venice highlighting key landmarks and mobility nodes, our study is grounded in the spatial reality of the city. We begin by analysing local resistance to mass tourism, then move through the spatial logic of transport hubs like Piazzale Roma. We further consider multilingualism and graffiti as forms of symbolic resistance, explore the role of governance in shaping visibility and authority, and finally, interpret the Santa Maria Maggiore prison as both a physical and discursive edge.

Anti-tourism

Santa Marta is a quiet and primarily residential place in Venice. Although Venice is renowned as a major tourist destination, anti-tourist sentiments are unequivocally presented in the Santa Marta area. Residents of Santa Marta are often inclined to preserve their region’s quiet, peaceful, and familiar way of life.

At Piazzale Roma, the main entry point to Venice, you’re welcomed not only by cats, buses, transport tickets, signs, and graffiti, but also by the political voice of the local. Messages such as ”Tourists go home! [Turisti andate a casa!]”, ”Venice is not a theme park [Venezia non è un parco a tema]”, ”Stop Airbnb [Fermate Airbnb]” reflect the growing discontent with mass tourism. These messages are embedded within public infrastructure and commercial zones captured in Figures 2-3, signalling local resistance to the commodification of space.

Locals frequently choose to express these messages in their native language as a way of voicing their feelings toward tourists. It may also reflect an effort to preserve and assert their local identity. This may explain the prevalence of anti-tourist discourses on the city walls as illustrated in Figure 4. As Shohamy and Gorter (2009) emphasize, the linguistic landscape reflects not only language choice, but power, control, and identity in contested urban environments.

While tourists are often viewed as intrusive, they is also an undeniable part of local reality, shaping income sources for many residents. The housing crisis serves as a tangible consequence of this complex relationship. Apartments are converted into tourist lodging, rents soar, and young people are pushed out. In Santa Marta, residents regard tourism as the primary driver of this gentrification. In this context, Figure 5 visually captures the spatial juxtaposition between local homes and tourist accommodations. Together, these visual and textual elements exemplify how the linguistic landscape functions as a mirror of social and economic tensions, illustrating how tourism-driven gentrification disrupts the everyday fabric of the Santa Marta neighbourhood.

Piazzale Roma: A Semiotic Node of Mobility

Piazzale Roma operates as a crucial semiotic and infrastructural gateway into Venice, where transport, signage, and spatial design converge to mediate movement and meaning. As the city’s principal intermodal hub, it connects terrestrial and aquatic systems, with the People Mover, parking facilities, and vaporetto docks forming a dynamic multimodal assemblage (Backhaus 2007; Jaworski and Thurlow 2010). This complexity is visually encoded in the signage shown in Figure 6, where color-coded categories and multilingual labels guide diverse users through the space.

This space is saturated with geosemiotic cues, signage, architecture, and human flow, that shape navigation and perception (Scollon and Wong Scollon 2003). Bilingual and tourist-oriented signs reflect strategic audience design, targeting international visitors while backgrounding local vernaculars (Shohamy and Gorter 2009). Such regimes of visibility govern who is seen and how, commodifying heritage and controlling spatial access (Gonçalves and Milani 2022). Piazzale Roma works not merely as a transport node but a textual and ideological territory, where urban branding and visual semiotics construct Venice as both a global city. Thus, its linguistic landscape reveals deeper power structures, where mobility is regulated not just physically, but symbolically.

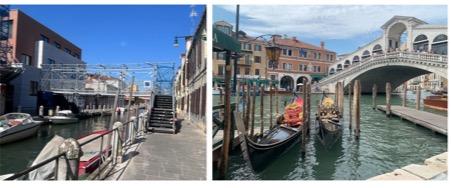

This symbolic regulation becomes even more apparent when contrasting Venice’s iconic and functional infrastructure, as shown in Figures 7–8, highlighting the semiotic tension between Venice’s temporary and iconic architecture. The industrial footbridge represents functional urban planning, yet remains visually marginalized, what Scollon and Wong Scollon (2003) term geosemiotic contrast. In contrast, the Rialto Bridge, framed by gondolas, serves as urban branding, projecting a curated tourist identity (Jaworski & Thurlow, 2010).

Temporary structures like the metal bridge are vital to local mobility but excluded from visual narratives. This reflects regimes of visibility, where heritage is elevated and everyday infrastructure is hidden (Gonçalves & Milani, 2022). Within the linguistic landscape, such spatial elements act as signs, embedded in a multimodal assemblage that communicates control, access, and economic priorities (Backhaus, 2007; Shohamy & Gorter, 2009).

Multilingualism and Symbolic Resistance

This piece of graffiti was found in the Santa Marta district of Venice, an area often overlooked by tourists, but still very much victim to the grapples of gentrification. Figure 9 illustrates a pigeon stencilled in grey with text below reading “Take a shit on gentrification”. Being a common urban fauna, the pigeon serves as a translingual symbol of resistance, satirising the displacement often linked to gentrification, through the use of crude language and strong imagery. Despite the dominance of the native Italian and Venetian languages in the region, the use of English in this graffiti transcends linguistic boundaries, particularly in a city that is frequently characterised by its global reach. A clear sense of irony is embedded into the symbolic nature of this image; with English most commonly being associated with global tourism and economic dominance, the message illustrated in the graffiti acts as a way of defiance against the very forces it usually enables. Pennycook (2010) argues that linguistic landscapes hold inherent political commentary, and through the use of multilingualism in this case, language has been assigned the role of symbolic resistance. This transforms a dominant language into a strong medium for protest with significant global influence. In a rapidly transforming urban environment, this act of graffiti reclaims the space through both physical and cultural displacement.

Government & Local Authority

Graffiti has long served as a powerful form of political expression, offering a voice to those who feel unheard and continue to provide valuable insight to an area that perhaps is normally more oppressed by mainstream institutions (Miladi 241). When moving around Santa Marta, one is struck by the tranquil atmosphere that it exudes, acting as a stark contrast to the bustle of the tourist centre of San Marco. However, while it seems relatively voiceless in the typical sense, it is the graffiti that is present throughout the district that is used as its voice, the anonymity providing a mask for the inhabitants to express their true feelings (Shobe 4).

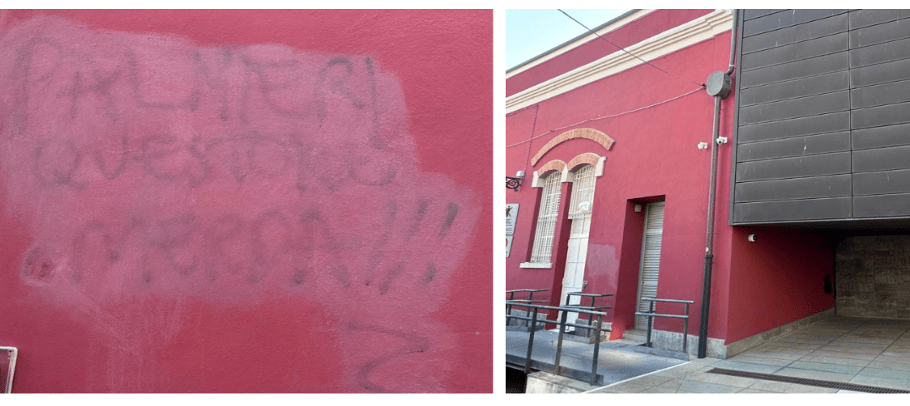

The graffiti encountered not only gave valuable insight into the political opinions of this district but told a story of both expression and oppression. Take Figure 10-11 for instance. This was present on the external wall of the questura with the text ‘Palmieri questore merda!!!’ which denounced Giampaolo Palmieri’s approach to crime prevention (the Director of the Anti-Crime Police Division of the Venice Police Headquarters.)

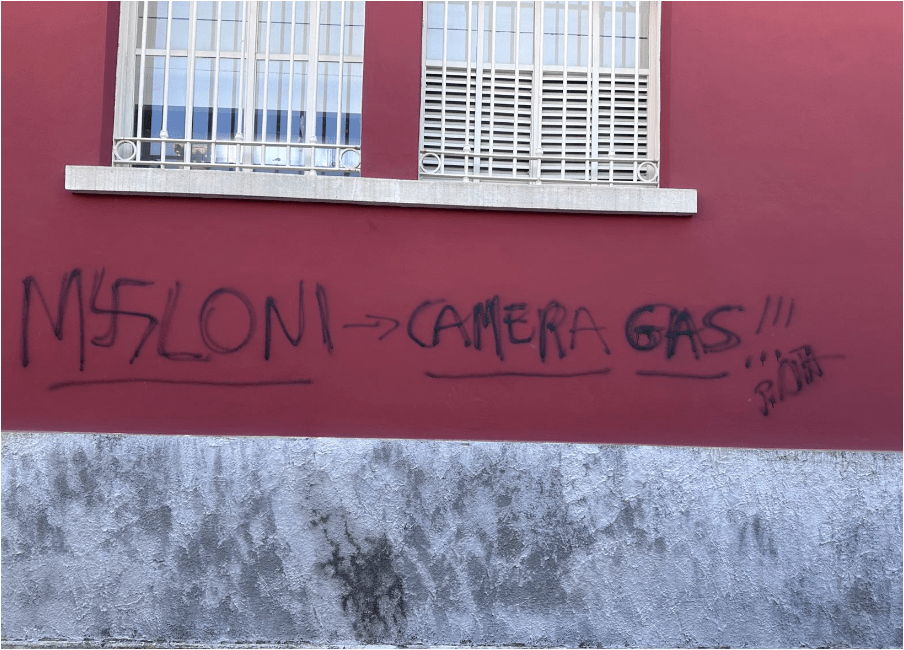

Interestingly, someone had attempted to remove this graffito, which shows the power struggle at play here; someone is speaking out against the local government and the institution is trying to censor their opinion. Conversely, further down the same wall there is another graffito (see Figure 12), which also expresses political opinions contrary to the institution. “Meloni -> Camera Gas!!!’. (“Meloni -> Gas Chamber!!!’ The inclusion of a swastika seems to imply that Italian Prime Minister is a Nazi.) Despite being a more extreme sentiment, this graffito has not been removed. Thus, just this one wall provides ample insight into the political opinions of the district. For them local political opinion is far more important compared to national political opinion.

While often dismissed as vandalism, political graffiti forces confrontation with uncomfortable truths and allows for a glimpse into the true feelings of the local community. Although it disrupts the visual landscape, making issues visible to all, its anonymity provides safety to artists allowing for a more honest take, no matter how vulgar it sometimes is. As both an art form and an act of rebellion, graffiti remains a vital tool for political expression, bridging art and activism to challenge the status quo and provoke change.

Prison as an edge

Assuming the urban pattern proposed by urban theorist Kevin Lynch (1960), in Santa Marta we have identified a district, a certain number of paths along which flows of people and vehicles are arranged and a nod in the mobility hub of Piazzale Roma. Within this framework, the prison, Santa Maria Maggiore, is certainly an edge, a physical boundary represented by a huge historic building located just in the middle of the district. The prison is in the historic city, in the proximity of houses, streets and passers-by.

This quite unusual status makes Santa Maria Maggiore an ambivalent boundary. On the one hand, the prison is a very solid barrier to be kept at a distance; on the other, it becomes a weird, somehow sinister, landmark that attracts converging energies and tensions from the surrounding environment. A heterotopic space, along the lines of Michel Foucault (1967), establishing a disturbing “world within the world”, in which the linguistic landscape turns the table and bends the rules.

As far as official signage is concerned, Figure 13 illustrates how institutional language conveys authority and regulation: “Mantenere la distanza di 2 metri da tutto il perimetro delle carceri” (“Keep a distance of 2 m. from the entire perimeter of the prison”). Such signs lay out practical rules designed to enforce both spatial and symbolic isolation.

Yet, the walls on both sides of the building are covered with writings calling for rebellion, revolt and freedom. Messages denouncing the prison system, suicides among prisoners and prison regimes likened to torture, such as the article 41-bis[TR1] of the Prison Administration Act.

Not all the writings are addressed to the general public, shown in Figure 14, reads: “Solidarietà ai reclusi. Forza ragazzi tenete duro” is one of the messages that can be found along the Fondamenta Procuratie. It is undoubtedly an expression of sympathy, written with the intention of being seen and read by Italian-speaking prisoners.

Brief historical research helped date the writings to about ten years ago. In fact, Google Maps makes it possible to go back in time and see if those writings were already present and when. Articles from newspapers were also another good source. There are at least two online articles about incursions by anarchists that took place in Venice in 2015 and 2016. Combining the results, it is highly probable that the writings of Santa Maria Maggiore were done on these occasions.

Through this collaborative exploration, we’ve seen how public space becomes a contested site where meanings are made, challenged, and redefined, offering insight into how ordinary urban elements are charged with symbolic power. In a city where every corner carries the weight of history and the pressure of global attention, even the smallest sign can speak volumes.

Works Cited

Backhaus, Peter. Linguistic Landscapes: A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo. Multilingual Matters, 2007.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias.” 1967. Foucault.info, https://foucault.info/documents/heterotopia/foucault.heteroTopia.en/. Accessed 21 July 2025.

Gonçalves, Kellie, and Tommaso M. Milani. Language, Urban Space and Political Agency. Routledge, 2022.

Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space. Continuum, 2010.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Blackwell, 1991.

Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. MIT Press, 1960.

Miladi, Noureddine. “Urban Graffiti, Political Activism and Resistance.” Routledge, 2018.

Pennycook, Alastair. Language as a local practice. Routledge, 2010.

Scollon, Ron, and Suzie Wong Scollon. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. Routledge, 2003.

Shobe, Hunter. “Graffiti as Communication and Language.” Handbook of the Changing World Language Map, edited by Stanley D. Brunn and Roland Kehrein, Springer, 2018,

Shohamy, Elana, and Durk Gorter, editors. Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery. Routledge, 2009.

[1] Berizzi Mariachiara – m.berizzi@stud.iuav.it

[2] Boam Olivia – ob377@exeter.ac.uk

[3] Fourie Nicholas Charles – nickfourie3@gmail.com

[4] Pizarro Jacinto Laura – lp557@exeter.ac.uk

[5] Yücel Dinç Fatma – fatmayuceldinc@mu.edu.tr

You must be logged in to post a comment.