Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Dr. Saphia Arezki, Associate researcher (IREMAM and CHERPA ,Aix-en-Provence)

When: 4-5:30pm, Wed. Jan. 22, 2020

Where: Queens building MR2+3, Streatham Campus, University of Exeter

Abstract

Having completed a thesis on the role of Algerian officers in the construction of a national army between 1954 and 1991, the focus of my postdoctoral research shifted to the 1990s in Algeria. Over the course of this decade, nearly 150,000 Algerians died, and the 1990s have come to be known as Algeria’s “black decade”. The precise nature of what took place remains a matter of debate. Was it a civil war? A war against civilians? Was it a fight against terrorism? While the term civil war is discussed but far from agreed upon, this broad descriptor perhaps best describes the reality that the country went through during the decade in question. The jurist Mouloud Boumghar justifies the use of this terminology in a way that seems convincing: “The term ‘war’ is used here in a non-legal sense of armed struggle between social and/or political groups with a goal of imposing by force a determined will on the adversary. It is described as civilian in order to mark its character as a non-international war between an established government and an insurrectional movement that challenges the former for the power of the state”[1]. Political scientists Adam Baczko and Gilles Dorronsoro propose a definition of civil war “as the coexistence on the same national territory of different social orders maintaining a violent relationship”[2] which is relevant in the Algerian context. Continue reading “Investigating the history of the 1990s in Algeria through the issue of repression – a talk by Dr Saphia Arezki”

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

The Court Room, Senate House, London

Call for papers

We will be running our next Decolonization Workshop here at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in Senate House, London, on Monday 16 March 2020. The day will run from 11.00am to 6.00pm.

As on previous occasions, we aim to have a series panel discussions over the course of the day. Each panel will consist of three papers lasting for 15-20 minutes. We are particularly appealing for proposals for presentations from research students and early-career researchers, although we welcome the participation of more established scholars. The workshop will provide an informal and supportive forum in which to discuss work in progress. Continue reading “CFP: Decolonization Workshop @ICwS_SAS, Monday 16 March 2020”

William Gallois

University of Exeter

While considerable literatures exist which describe interactions between European modernist art and local forms of culture, Tunisia is quite typical in being a site in which scholars know very little about indigenous forms of artistic production in the late- nineteenth and eraly-twentieth centuries. Colonists generally disparaged the paintings of locals as being instances of folk art, art brut, popular culture or graffiti, while such judgements have also tended to be replicated in the work of scholars of empire right up until our present. While a work of abstraction by Matisse or Klee is accorded value in the setting of a western museum, similar shapes and forms found painted onto walls and paper in north Africa have been viewed as crude instances of a backward culture.

Through a process of what Maziyar Ghiabi calls ‘visual archaeology’, contemporary scholars are, however, able to relocate and, in some cases, reproduce artworks from the margins of colonial-era photography and ephemeral forms such as postcards and advertisements. What such discoveries reveal in Tunisia, and across Islamic Africa, are the existence of vast corpuses of complex, beautiful and powerful works of art almost exclusively made by women. These paintings drew on traditiona forms of cultural expression in radically new ways so as to make pictures which would protect subjugated populations from the violence of colonial rule.

This got me thinking that Instagram could be an interesting place to explore the subject further, as it seems an especially apt venue for those who work primarily with images. As well as potentially exposing wider publics to new research, it has especial appeal as a means of democratically engaging audiences in the global South. I realise that some would question how the granting of intellectual property to a western digital behemoth is any sense a decolonial act, but given the manner in which scholars in the Humanities are in thrall to exclusionary paid-for publishing options, I’d suggest that it merits consideration as a means of speaking outside of the world of paywalls. Continue reading “Researching the Colonial Past on Instagram”

HERRENHAUSEN CONFERENCE, SEPTEMBER 13-15, 2020

Governing Humanitarianism: Past, Present and Future

HERRENHAUSEN PALACE, HANOVER, GERMANY

TRAVEL GRANTS AVAILABLE

for Early Career Researchers and Young Professionals

Deadline: March 15, 2020

Apply here: https://call.volkswagenstiftung.de/calls/antrag/index.html#/apply/80

The Topic

Humanitarian organisations across the globe face growing challenges in delivering aid, securing funds and maintaining public confidence. Trade-offs between sovereignty, democracy, security, development, identity, and human rights have become highly complex. The Herrenhausen Conference ‘Governing Humanitarianism’ interrogates present issues and future directions for global humanitarian governance in relation to its pasts. It asks if humanitarian expansion has come at the expense of core values and effective intervention, and how the pursuit of global equity and social justice can be pursued through shifting global and local power structures. The conference features six key themes: Humanitarianism as Global Networks and Activism; Gendering Humanitarianism; Humanitarianism and International Law; Humanitarian Political and Moral Economies; Media and Humanitarianism; Humanitarianism, Development and Global Human Rights. Continue reading “Travel Grants Available – Governing Humanitarianism: Past, Present and Future Conference”

Ulrike Zitzlsperger

University of Exeter

Cross-posted from the Exeter Language and Culture Blog

On 9 November 2019 Berlin is once more the central location for celebrations commemorating the fall of the Wall, the physical divide between East and West Germany and unique symbol of the Cold War. In 2019 the Wall will have been gone for more years than it actually stood.

Developed from August 1961 to stem the growing exodus of a skilled work-force, the Wall allowed the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to become the success story of the Warsaw Pact. However, time and again people risked everything to escape to the West. Even if they were successful they left their former lives behind and knew that any remaining family would be punished by the state: costing them, for example, that much longed-for place to study at University or a trip abroad. There were more sinister options too. In Berlin, so-called frontier-city of the Cold War, the Wall encircled the Western part of the city, measuring between 3.4 and 4.2 metres in height. There is a memorable scene in Steven Spielberg’s film Bridge of Spies (2015), when one of the protagonists watches lone figures from the inner-city railway desperately climbing the Wall. The scene is fiction – just like the scene in the Alfred Hitchcock film Torn Curtain (1966) that makes us believe that GDR citizens hijacked buses with passengers on board to escape. The Wall never needed this kind of embellishment: it was sufficiently surreal, monstrous and overwhelming as it was, including the death-strip in between both Walls – one facing West, one East. Continue reading “Marking thirty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall”

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Jeffrey A. Auerbach. Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. pp.320. ISBN: 9780198827375; £35.00

Reviewed by Amina Marzouk Chouchene (PhD candidate, Manouba University)

The British Empire has been firmly tied to myth, adventure, and victory. For many Britons, “the empire was the mythic landscape of romance and adventure. It was that quarter of the globe that was colored and included darkest Africa and the mysterious East.”[1]Cultural artifacts such as music, films, cigarette cards, and fiction have long constructed and reflected this rosy vision of the empire as a place of adventure and excitement. Against this widely held view of the empire, Jeffrey Auerbach identifies an overwhelming emotion that filled the psyche of many Britons as they moved to new lands: imperial boredom. Auerbach defines boredom as “an emotional state that individuals experience when they find themselves without anything particular to do and are uninterested in their surroundings.”[2]

Auerbach identifies the feeling as a “modern construct” closely associated with the mid-eighteenth century. This does not mean that people were never bored before this, but that they “did not know it or express it.”[3] Rather, it was with the spread of industrial capitalism and the Enlightenment emphasis on individual rights and happiness that the concept came to the fore.

In a well-researched and enjoyable book, the author argues “that despite the many and famous tales of glory and adventure, a significant and overlooked feature of the nineteenth century British imperial experience was boredom and disappointment.”[4] In other words, instead of focusing on the exploits of imperial luminaries such as Walter Raleigh, James Cook, Robert Clive, David Livingstone, Cecil Rhodes and others, Auerbach pays particular attention to the moments when many travelers, colonial officers, governors, soldiers, and settlers were gripped by an intense sense of boredom in India, Australia, and southern Africa. Continue reading “Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire”

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Gil Shohat

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

On a Sunday afternoon in June 1938, the International African Service Bureau (IASB) held one of its numerous rallies at Trafalgar Square in central London. As one of the prime anti-colonial organisations of that time based in London and comprised of activists from West- and East Africa as well as from the West Indies,the gathering was closely monitored by the Metropolitan Police. The sergeant on duty reported that the demonstration was “attended by an audience fluctuating between 100 and 250 persons, of whom approximately 15% were Jews”. Speakers at the protest included, among others, Jomo Kenyatta (later first president of Kenya), the Trinidadian intellectual C.L.R. James, the Jamaican dockworker Chris Jones, and the Pan-Africanist activist and journalist George Padmore. Furthermore, the informant took notice of placards containing slogans such as “Fascism in the British Empire”, “Abolish fascist methods in the Colonies”, and “Imperialism is incompatible with peace”. The speakers repeatedly denounced the evil practices of British Imperialism and Colonialism in its territories and warned against any form of acquiescence with the Empire regarding the surging threat of fascism posed by Italy and Nazi-Germany. What’s more, they explicitly drew parallels between the practice of British and French colonialism and the policies and actions of their fascist rivals. In short, for the IASB combatting fascism could not be done without simultaneously overcoming imperialism from within.[1]

This event was by no means a forum for black activists alone. There were also numerous white British speakers from the left who contributed to the demonstration. Francis Ridley is a case in point. Ridley was a leading figure in the Independent Labour Party (ILP), which was arguably the most consistent of British leftist parties when it came to the question of

how to act in solidarity with anti-colonial and anti-imperial activists in the metropolis. Next to Fenner Brockway, the long time ILP chairman, editor of the party weekly and later Labour MP and the Quaker and Socialist activist and author Reginald Reynolds, Ridley can retrospectively be regarded as a defining figure of British anti-imperialist activism from the 1930s to the 1950s. Tellingly, he was described by the police informant at the scene as a “white man”, in order to highlight the supposedly extraordinary nature of his participation in the rally. In his speech, Ridley demanded that the “democratic conditions under which the people of England lived should be extended to the black workers of the Empire. Much talk was made today of the hardships suffered by the minorities in fascist countries, but these minorities were being treated very well in comparison to the negroes in the British Empire.” Ridley thus attempted to bring the suffering of colonized peoples in the “periphery” into the “metropolis” by connecting it to the condition of subaltern peoples of Europe. The example presented here thus hints at emerging and previously underrated cross-sectional solidarities among the numerous ethnic and social groups of London. Continue reading “Rethinking Anti-Colonial Activism Through London’s Surveillance Material”

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Cross-posted from Humanitarianism & Human Rights

Academic Conveners: Fabian Klose (University of Cologne), Johannes Paulmann (IEG Mainz), Andrew Thompson (University of Exeter) in cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross (Geneva)

Date: 07.07.2019-19.07.2019, Mainz / Geneva

The fifth edition of the Global Humanitarianism Research Academy (GHRA) took place at the Leibniz Institute of European History Mainz and the Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva from July 7 to 19, 2019. It approached cutting-edge research regarding ideas and practices of humanitarianism in the context of international, imperial and global history thus advancing our understanding of global governance in humanitarian crises of the present. With the Chair in International History and Historical Peace and Conflict Studies at the Department of History of the University of Cologne, a new partner joined the GHRA 2019. As in the last four years the organizers FABIAN KLOSE (University of Cologne), JOHANNES PAULMANN (Leibniz Institute of European History Mainz), and ANDREW THOMPSON (University of Exeter) received again a large number of excellent applications from more than twenty different countries around the world. Eventually the conveners selected eleven fellows (nine PhD candidates, two Postdocs) from Brazil, Cyprus, Egypt, Ireland, Japan, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The multitude of disciplinary approaches from International Law, Political Science, and Medicine proved to be very rewarding just as the participation of guest lecturer CLAUS KREß (University of Cologne), visiting fellow JULIA IRWIN (University of South Florida, Tampa) as well as STACEY HYND (University of Exeter) and MARC-WILLIAM PALEN (University of Exeter) as long-standing members of the academic team. Continue reading “Report of the Fifth Global Humanitarianism Research Academy (GHRA 2019)”

Ryan Hanley

University of Exeter

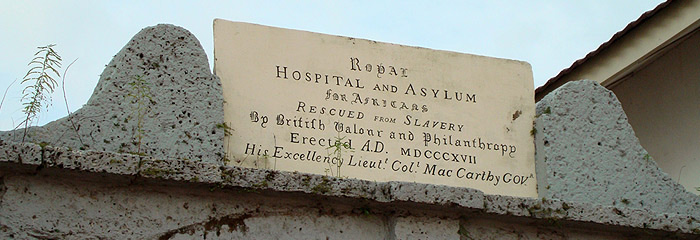

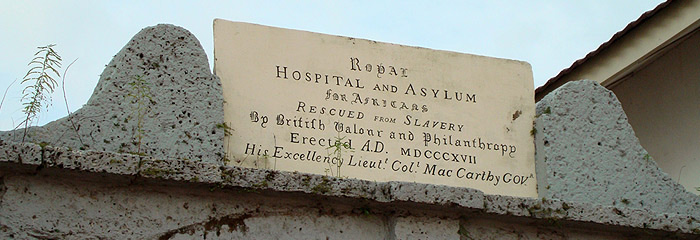

October marks Black History Month in the UK, providing the perfect excuse to delve into some of the best new history writing in this dynamic and rapidly-expanding field. Since my first monograph, Beyond Slavery and Abolition: Black British Writing, c.1770-1830 (Cambridge University Press, 2018), was published last October, the field of black British history seems to have been completely transformed. The past twelve months have seen several (I counted six) new permanent academic posts in the UK and a new MA programme, all dedicated more or less specifically to black British history. And January 2020 sees the launch of a new seminar series in London supported by the Institute for Historical Research, showcasing some of the best new work in the field from within and beyond the university – hope to see some of you there!

Some of this will have to do with the publication in October 2018 of the Royal Historical Society’s Race, Ethnicity and Equality Report, which highlighted the chronic underrepresentation and overwork of ‘Black and Minority Ethnic’ academic staff in British history departments. But the sudden heightened visibility of black British history in UK academia is not purely down to newfound resolutions to build stronger, better history departments, nor solely to the ongoing work to ‘decolonise’ history curricula, though both are important factors. The simple fact is that we have had an incredible year of high-quality scholarly research publications, accounting for some of the most innovative, dynamic, and vital work on British history as a whole.

Don’t call it a ‘turn’ – but there is more and more great work out there that, taken together, is changing the way we think about Britain’s past and its relationship to global and imperial history. Some of you, especially if you don’t work on topics obviously related to black British history, might be curious about how this impacts on your research interests. So, to celebrate and spread the word about this new wave of black British history scholarship, here are my top picks from the past twelve months. Continue reading “New Books on Black British History”

You must be logged in to post a comment.