Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

Living in the Age of the Storyteller: Global History and the Politics of Narrative

Lori Lee Oates

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @LoriLeeOates

In late June, I had the honour of hearing Professor David A. Bell speak at the Society for the Study of French History conference at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. The theme of the conference was Turning Points in French History and he spoke on the period between 1715 to 1815. Professor Bell went on to discuss ‘the global turn’. He noted that a significant percentage of current history Ph.D. students are using global analysis as the main methodology for their thesis. He then discussed the limits of this methodology, particularly as a largely structural analysis. He argued that the methodologies of ‘the linguistic turn’ might actually be more helpful to us in analyzing the process of why change continues after these same global structures break down. Linguistic analysis largely views language as a structure that is culturally inherited and something that limits our ability to comprehend society beyond those concepts that are available to us in our immediate environment.

As one of many Ph.D. students who have turned toward using global and imperial methodology, I was intrigued. Professor Bell’s talk also reminded me of sitting in an Ex Historia seminar on global and imperial history in 2013 and posing the question of whether this was just another passing academic fad. Like others I had been advised to do a thesis that is an analysis of the effects of globalization and the inherent influence of imperialism on that process. In many ways this is a good approach as a number of new academic positions are being created in the field of global and imperial history on both sides of the Atlantic. However, given the academic hype regarding globalization in recent years, I had honestly been wondering for some time when somebody was going to start questioning the efficacy of the methodology. Continue reading “Living in the Age of the Storyteller: Global History and the Politics of Narrative”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From the memory of Soviet famine to how a Sioux chief was buried in Dresden, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

The Jameson Raid and the ‘Cheap Extension of Empire’

Simon Mackley

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @SimonMackley

What was the nature of British imperial expansion? Did British imperialism constitute a form of globalisation? These were the questions put to the participants at the opening of the 2015 International PhD Forum at Peking University on 10th July, which Simon attended as part of a delegation from the University of Exeter, along with postgraduates from PKU and the University of Durham. Drawing on his wider doctoral research into the British Liberal Party and the South African question in late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain, Simon seeks to tackle the first question by analysing the Liberal critique of the British South Africa Company following the Jameson Raid of 1895, and the form of imperialism it was alleged to represent.

The end of 1895 had seen British South African Company (BSAC) forces, under the direction of Cecil Rhodes, launch an attempted invasion and coup against the South African Republic. The action, which became known as the Jameson Raid, was a total failure, but the political fallout in Britain was immense, with a particular focus on the relationship between the Chartered Company and the conspiracy. In seeking to further our understandings of the nature of British imperial expansion, the Jameson Raid might seem like an odd choice of focus by comparison with other episodes in Imperial South African history; although an important precursor to the South African War of 1899-1902, the Raid itself provided no territorial gains for the Empire, and indeed arguably weakened the British position in the region. However, an analysis of the political controversy generated by the Raid in Britain, and particularly the public rhetoric deployed by political actors, provides real insight into how the expansion of the Empire and the forces of imperialism operated as political issues within late-Victorian Britain. Continue reading “The Jameson Raid and the ‘Cheap Extension of Empire’”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From the Cuban Revolution that almost wasn’t to the Sushi Craze of 1905, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

Imperial History in a Post-Imperial Setting: Power, Patriarchy and Pardon

![Chinese scroll with illustration of the iron steamer Nemesis and a British man-of-war, accompanied by a 55-line Chinese poem [1840c_ChScrollNemesis_D40019-04_left]](https://imperialglobalexeter.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/nemesis.gif?w=504&h=252)

Catriona Pennell

History Department, University of Exeter

In 1942, Arthur Waley – English orientalist and sinologist – described the first two decades of the twentieth century as ‘a great turning point’ in Anglo-Chinese relations. It was in this period that poets, professors and thinkers began to visit China instead of soldiers, sailors, missionaries, merchants and officials.[1] These ‘men of leisure’ travelled ‘not to convert, trade, rule or fight, but simply to make friends and learn’.[2] Over seventy years later, these sentiments were at the forefront of the international PhD symposium on ‘Imperial Expansion and Globalization’ convened to ‘mark the friendship between the Department of History at University of Exeter, Durham University and Peking University’ between 10 and 13 July 2015.[3] Over the course of four intense days, twelve PhD students and three academics immersed themselves in debate, discussion and cultural exchange. While the topics of the papers covered Warley’s four core issues of imperial contact – belief, economics, governance and conflict – the atmosphere was always cordial and welcoming.

I felt privileged that my first visit to China was within this setting of cultural and academic accord. Spending time with our hosts, both in the formal setting of the symposium and during our “downtime” visiting some of Beijing’s most famous landmarks, gave me a good deal of time to reflect on what it meant to partake in intellectual exchange on the history of empire in a post-imperial setting. How far had we really moved into a post-colonial era? Was our academic relationship genuinely based on mutual respect and understanding? The remnants of Britain’s colonial relationship with China were never far away. This was both obvious – in the fact that the working language of the symposium was English – and more subtle; for example, the realisation that the phrase ‘I won’t kowtow’ originated from the British McCartney Mission to China in 1793.[4] There were also gentle reminders of other European influences; as a vegetarian a staple (and delicious) food item during our visit was “danta” – miniature savoury egg tarts based on the Portuguese recipe introduced to China via its first and last European colony, Macau. Continue reading “Imperial History in a Post-Imperial Setting: Power, Patriarchy and Pardon”

British Historians and British Identity

Anthony Leon Brundage and Richard Alfred Cosgrove. British Historians and National Identity, From Hume to Churchill. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2014. 272 pp. £60.00 (hard back), ISBN 978-1-84893-539-6; £24 (eBook).

Reviewed by Rachel Chin

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @chinra4

In the last two decades, historical studies focussing on themes of memory creation, mythmaking and national identity have burgeoned.[1] Authors Anthony Brundage and Richard A. Cosgrove, in their 2014 book British Historians and National Identity, attempt to link a series of single-authored multi-volume histories to the creation of particular themes within British identity. The central thesis of the work is that British national identity was never, and is not today, a static concept: “Central to the manner that English people think of themselves was (and is) their history: real, imagined or invented; all categories of identity are rooted in some century or era of the English story”[8]. By focussing upon British history specifically, Brundage and Cosgrove have been able to narrow the scope of their ambitious work to the development of an historical framework in which historians themselves advanced and influenced the exceptional island story.

In the last two decades, historical studies focussing on themes of memory creation, mythmaking and national identity have burgeoned.[1] Authors Anthony Brundage and Richard A. Cosgrove, in their 2014 book British Historians and National Identity, attempt to link a series of single-authored multi-volume histories to the creation of particular themes within British identity. The central thesis of the work is that British national identity was never, and is not today, a static concept: “Central to the manner that English people think of themselves was (and is) their history: real, imagined or invented; all categories of identity are rooted in some century or era of the English story”[8]. By focussing upon British history specifically, Brundage and Cosgrove have been able to narrow the scope of their ambitious work to the development of an historical framework in which historians themselves advanced and influenced the exceptional island story.

This particular study is unique in that it links the work of a series of historians, from David Hume to Sir Winston Churchill, with the goal of demonstrating how “history (and historians) provide the collective memory for the nation.” [248] Fascination with the idea of identity construction, particular within a British, or more often, specifically English framework, has previously been taken up by a number of scholars. Linda Colley’s Britons: Forging the Nation (2009) represents particularly well the extent to which British identity was constructed around or indeed, against the idea of an enemy ‘other’: namely, the French.[2] Likewise, as is evident with Anglo-French scholar Robert Tombs’ recent publication The English and Their History (2015), this is a topic that continues to draw intellectual scrutiny.[3] Engagement with memory creation and identity within the context of war and conflict remain popular areas of research, with Samuel Hynes and Mark Connelly, in the last decade or so, analysing the process of selection through which shared memory and personal narratives become collective.[4] Jonathan Rose’s The Literary Churchill (2014) and David Reynolds’ In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War (2004) in turn take a specialised and extremely personal approach in working to shed light upon how one political actor and historian understood and interpreted their own achievements.[5] Continue reading “British Historians and British Identity”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From the centenary of the “humanitarian occupation” of Haiti to internationalizing the ruins of Palmyra, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

Global Humanitarianism Research Academy 2015 – Week 2

Cross-posted from Humanitarianism & Human Rights

After the first week of academic training at the Leibniz Institute of European History in Mainz, the Global Humanitarianism Research Academy (GHRA) 2015 travelled for a week of research training and discussion with ICRC members to the Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva.

GHRA participants in the ICRC Archives

GHRA participants in the ICRC Archives

The First Day at Geneva started with an introduction to the public archives and library resources by ICRC staff. Jean-Luc Blondel, former Delegate, Head of Division, and currently Adviser to the Department of Communication and Information Management welcomed the group. Daniel Palmieri, the Historical Research Officer at the ICRC, and Fabrizio Bensi, Archivist, explained the development of the holdings, particularly of the recently opened records from 1966-1975. The Librarian Veronique Ziegenhagen introduced the library with its encompassing publications on International Humanitarian Law, Human Rights, Humanitarian Action, international conflicts and crises. The ICRC also possesses a superb collection of photographs and films which Fania Khan Mohammad, Photo archivist, and Marina Meier, Film archivist explained. Continue reading “Global Humanitarianism Research Academy 2015 – Week 2”

The Colonial Origins of the Greek Bailout

Jamie Martin

Harvard University

Follow on Twitter @jamiemartin2

When news broke two weeks ago of the harsh terms of a new bailout for Greece, many questioned whether the country still qualified as a sovereign state. “Debt colony,” a term long used by Syriza and its supporters, was suddenly everywhere in the press. Even the Financial Times used the language of empire: “a bailout on the terms set out in Brussels,” as a 13 July editorial put it, “risks turning the relationship with Greece into one akin to that between a colonial overlord and its vassal.”

Suggestions like these have invited historical comparison. One parallel that’s been mentioned is that of Egypt during the late nineteenth century. In 1876, as a heavily indebted Egypt approached bankruptcy, the Khedive Ismail Pasha agreed to the creation of an international commission, staffed by Europeans, with oversight of the Egyptian budget and control over certain sources of public revenue. This arrangement, designed to ensure the timely servicing of foreign debts, opened a new and extended period of intensified European intervention in Egypt – the Caisse de la Dette Publique was not abolished until 1940.

In the case of Greece, the comparison to nineteenth-century Egypt carries polemical weight largely as metaphor: Eurozone leaders should not treat Greece as if it were a semi-colonial territory. But there’s more at work here than just metaphor – at least historically speaking. As recent works in international history have demonstrated, there are important, and often obscured, continuities between the institutions and practices of European imperialism and the systems of global governance created or expanded in the second half of the twentieth century.[1] Continue reading “The Colonial Origins of the Greek Bailout”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From 21st-century US filibustering in Africa to how to make a country disappear, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

Global Humanitarianism Research Academy 2015 – Week 1

Cross-posted from Humanitarianism & Human Rights

After the first part the Global Humanitarianism Research Academy (GHRA) 2015 at the Leibniz Institute of European History in Mainz the next week of academic training will take place at the Archives of International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva.

On Day One recent research and fundamental concepts of global humanitarianism were critically reviewed. Participants discussed crucial texts on the historiography of humanitarianism and human rights. Themes included the historical emergence of humanitarianism since the eighteenth century and the troubled relationship between humanitarianism, human rights, and humanitarian intervention. Further, twentieth century conjunctures of humanitarian aid and the colonial entanglements of human rights were discussed. Finally, recent scholarship on the genealogies of the politics of humanitarian protection and human rights since the 1970s was assessed, also with a view on the challenges for the 21st century. Continue reading “Global Humanitarianism Research Academy 2015 – Week 1”

This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

From revealing the sheer scale of British slave ownership to America’s colonial fiscal crisis, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history. Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”

Call For Papers – Colonialism, War & Photography

Call for Papers for an Interdisciplinary Workshop as part of the research project

Cultural Exchange in Times of Global Conflict: Colonials, Neutrals and Belligerents during the First World War

Colonialism, War & Photography

London – 17 September 2015

If the First World War is usually defined as the military clash of empires, it can also be reconceptualised as a turning point in the history of cultural encounters. Between 1914 and 1918, more than four million non-white men were drafted mostly as soldiers or labourers into the Allied armies: they served in different parts of the world – from Europe and Africa to Mesopotamia, the Middle East and China – resulting in an unprecedented range of cultural encounters. The war was also a turning point in the history of photographic documentation as such moments and processes were recorded in hundreds of thousands of photographs by fellow soldiers, official photographers, amateurs, civilians and the press. In the absence of written records, these photographs are some of our most important – and hitherto largely neglected – sources of the lives of these men: in trenches, fields, billets, hospitals, towns, markets, POW camps. But how do we ‘read’ these photographs?

Using the First World War as a focal point, this interdisciplinary one-day workshop aims to examine the complex intersections between war, colonialism and photography. What is the use and influence of (colonial) photography on the practice of history? What is the relationship between its formal and historical aspects? How are the photographs themselves involved in the processes of cultural contact that they record and how do they negotiate structures of power? Continue reading “Call For Papers – Colonialism, War & Photography”

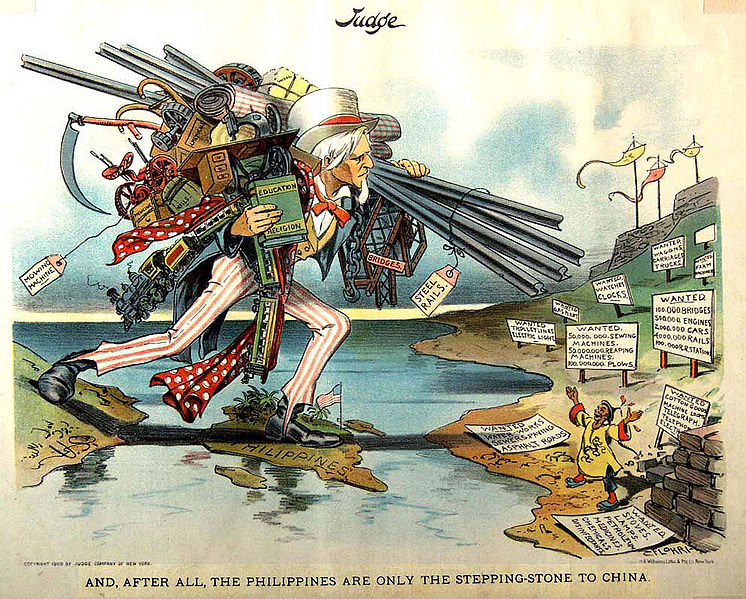

The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Imperial Preference Reborn?

Peter E. Hamilton

University of Texas at Austin

Empires are in motion in the Pacific. While China continues to assert its military muscle in the East and South China Seas, it is simultaneously ramping up a “soft power” offensive through the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). This Chinese-led institution represents the opening salvo in a sustained effort to decenter US-dominated institutions such as the World Bank from exclusive leadership over global capitalism. Indeed, China is also adding momentum to its proposed Free Trade Area of Asia Pacific (FTAAP), a free trade zone that would include many US allies but not the United States. Increasingly sensitive about this competitor, the United States is now rushing to reinforce the imperial perimeter that it has held across most of Asia’s coastline since the end of World War II.

As a result, on June 24 the US Congress granted the Obama administration what is called “fast track” or trade promotion authority to complete negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This vast free trade agreement will cover the United States and eleven of its principal Pacific partners—together nearly 40 percent of the global economy. From Japan, Canada, and Mexico to Chile, Malaysia, and Vietnam, each potential signatory is either a key US ally or very invested in maintaining US leadership in the Pacific.

China’s absence is glaring. Moreover, while fast-track authority makes the TPP far more likely by prohibiting death by Congressional amendment, this practical step also underscores that the administration and Congress (primarily Republicans) both view this deal through a strategic lens and its potential to cement non-Chinese relationships. The actual details are seen as far less important and have been largely entrusted to multinationals’ lobbyists. When these complex and now highly secretive terms debut, Congress and the public will likely be railroaded into their wholesale acceptance. The TPP thus offers a new iteration of the United States’ and other empires’ longstanding use of market access to cement informal control over allies and client states. Continue reading “The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Imperial Preference Reborn?”

You must be logged in to post a comment.