Nandini Chatterjee

History Department, University of Exeter

Review of Poonam Bala ed. Medicine and Colonialism: Historical Perspectives in India and South Africa. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2014. Empires in Perspective Series. 240 pp. £60 (hardback) ISBN 13: 9781848934658; £24 (e-book) 9781781440872.

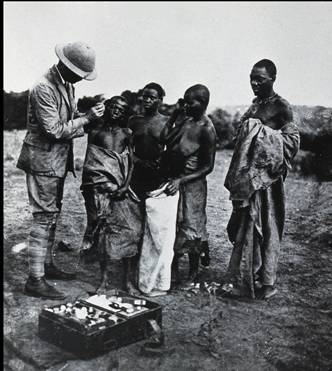

The recent surge of interest in imperial history has been cross-fertilised by work on a number of other themes, such as knowledge formation, law and governance and trans-national connections. This collected volume of essays very usefully brings together a number of these trends to bear upon the crucial area of colonial medicine. Self-consciously aiming to be a comparative work and taking material from India and South Africa, it takes its cue from earlier works that aimed to ‘de-centre’ the metropolis-periphery model of conceptualising empire and colonialism.[1] While re-asserting the centrality of medical knowledge and practices to colonial rule, and the importance of the bodies of the colonised as sites for the exercise of colonial power, the book aims to move beyond a model of hegemony, domination and control. Instead, as the introductory essay outlines, the book’s trans-national methodology is intended to highlight ‘policies of European adaptation and resistance to initiatives of the colonized’ and the ‘transfer of ideas and knowledge in mutual engagements.’

The recent surge of interest in imperial history has been cross-fertilised by work on a number of other themes, such as knowledge formation, law and governance and trans-national connections. This collected volume of essays very usefully brings together a number of these trends to bear upon the crucial area of colonial medicine. Self-consciously aiming to be a comparative work and taking material from India and South Africa, it takes its cue from earlier works that aimed to ‘de-centre’ the metropolis-periphery model of conceptualising empire and colonialism.[1] While re-asserting the centrality of medical knowledge and practices to colonial rule, and the importance of the bodies of the colonised as sites for the exercise of colonial power, the book aims to move beyond a model of hegemony, domination and control. Instead, as the introductory essay outlines, the book’s trans-national methodology is intended to highlight ‘policies of European adaptation and resistance to initiatives of the colonized’ and the ‘transfer of ideas and knowledge in mutual engagements.’

The essays themselves achieve these aims to a significant extent, if not uniformly. Among the three essays on cultural exchanges and contests in the field of colonial medicine, Poonam Bala’s essay on the growing advocacy of indigenous Indian medicine (mainly Ayurveda) as an element of Indian nationalism could have said more (given the title of the chapter) about the precise role that caste played in this dynamic, and offered some further details about the curriculum, functioning and impact of the new Ayurveda colleges that were established in the early twentieth century. Steve Phatlane’s essay condemns the continued refusal of the post-Apartheid South African government to embrace indigenous medicine in the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Phatlane’s paradigm of cultural conflict allows him to say little about exchanges, and his passionate advocacy of indigenous medicine as most culturally and economically suitable for Africans leaves questions of medical efficacy unanswered. Russel Viljoen’s article on the sharing of medical expertise, services and medicine between the Khoikhoi communities and the European settlers in Cape Colony presents rich material, pertaining to substantial and sustained exchanges between the seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries. Especially interesting are the many instances of medical services rendered by Khoikhoi doctors and midwives to the Europeans settlers; the section on nineteenth-century European medical racism, while relevant, ties in with this somewhat artificially.

Among the essays on epidemics and public health, Samiparna Samanta’s essay on rinderpest or cattle plague shows how outbreaks of epizootics in late nineteenth-century Bengal provided occasions for asserting the superiority of European medical knowledge, and for the hybridization of Indian sacred norms and western science in the Bengali urban elite’s espousal of vegetarianism. But it is left unclear why cattle plague inspired such major dietary concerns among Bengali Hindus, most of whom presumably never ate beef. Howard Phillips uses Gandhi’s letters in comparison with his published autobiography to reveal Gandhi’s disdain for the low standards of hygiene among South African Indians, which he held partly responsible for the outbreak of epidemic disease among them. Phillips exposes Gandhi’s complicity in the South African government’s racially motivated compulsory relocation programme for the Indian community affected by the disease and his racist disapproval of Africans co-residing with Indians. Natasha Sarkar’s essay on intrusive public health measures aimed at preventing or containing the impact and spread of plague in India and South Africa at the turn of the century reveals the pointlessness of many of these measures, based as they were on prejudices that then had the status of scientific truth. Both Phillips’ and Sarkar’s trans-national essays offer concrete instances of the inter-twining of prejudice and power in the practice of colonial medicine; while Katherine Royer’s largely historiographic essay charts the formation of one such medical prejudice. She shows how the rat-centric theory of plague propagation, initiated by the Indian Plague Commission of 1898, obscured many other forms of the disease and patterns of its propagation until recently.

On maternal and reproductive health, Arabinda Samanta’s essay offers an corrective history of the lesser-known efforts by certain Bengali doctors to improve women’s childbirth experience, among other things by their development of appropriate surgical instruments, and the frustration of their efforts by a colonial government with its own ‘private agenda’ of enforcing other forms of medical modernity.

Of the two essays on insanity, Jonathan Saha’s presents two sets of case studies related to the Andaman Islands and Burma – to show that while colonial psychiatry was a disciplinary regime, categorising, controlling and punishing the colonised, the identification of psychosis was a fraught endeavour, fractured as it was by debates among medical professionals, and between different arms of the government motivated by various imperatives. Sally Swartz’s essay uses archival material related to the Valkenburg Lunatic Asylum, opened in 1891, to question academic commonplaces that posit ‘custodial care in mental institutions as political or inhumane’ and instead proposes several alternative and complementary methodological approaches to the study of asylums as social institutions.

Jeffrey M. Jentzen’s essay on the history of medical jurisprudence in India and South Africa is a loosely structured narrative presenting various developments in this field in the two colonies. It would have benefited from a tighter argument, and from excising irrelevant material, such as the development of ballistic technology in India, and the legal history of Egypt.

Unfortunately, the language is obscure in several places, and authors have not followed a consistent method of citing books and articles (some preferring to include full book titles in-line). Also, some more effort could have been made to draw the chapters together to address a common set of analytical points. For example, the theme of exchanges, highlighted in the introduction, did not connect particularly well with many of the essays. The reader is also left to construe why India and South Africa were chosen as apt entities for comparison – beyond the requirements of project funding. Furthermore, the e-book is presented in Adobe Digital Editions, which in its current form does not seem particularly suitable for academic books, because it does not allow smooth navigation between footnotes and the text (once one has clicked on a footnote, one has to remember the page number and click one’s way back to it).

Despite this, the book performs the important task of bringing together a number of interesting research projects, and will be of interest to researchers and teachers not only in the field of medical history, but also imperialism and law, colonial knowledge formation and trans-national connections.

[1] Such as Durba Ghosh, De-centering Empire: Britain, India and the Transcolonial World, London: Sangam, 2006.

2 thoughts on “Exchanging Notes: Colonialism and Medicine in India and South Africa”

Comments are closed.