Tobias Rupprecht

History Department, University of Exeter

‘This is a great conservative system,’ reported the visitor following his trip to Moscow, ‘there is no lack of order, no anarchy, no lack of discipline! Everyone respects the authorities!’ While the liberal leaders of the materialist and soulless West allegedly no longer took up a stance against decadent art, degenerate music, and immoral sexual libertarianism, the leaders in the Kremlin, he claimed, heroically defended traditional family values and a ‘healthy patriotism’.

The tone of this argument will sound rather familiar to a contemporary observer of Russia’s reactionary domestic policies and its regression to Cold War style foreign intervention. A swashbuckling Vladimir Putin has attracted the tacit, and sometimes open, admiration from many Europeans who no longer feel represented by what they see as the liberal mainstream in politics and media.

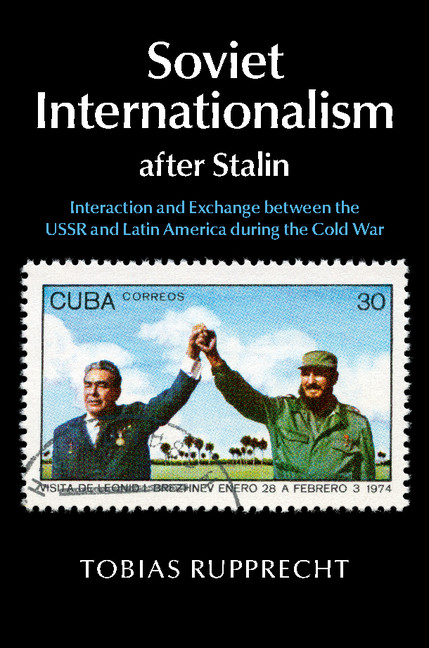

Yet in this case, the visitor to Moscow was a Alberto Dango, lawyer from Bogotá – and his trip took place as early as 1967. Dango was a member of the Conservative Party in the Colombian Parliament. His diary from the motherland of socialism (“Mi diario en la Unión Soviética. Un conservador en la U.R.S.S.”) is one of many documents that I have unearthed for my recently published book Soviet Internationalism after Stalin, which assesses the specific Soviet way of participating in an increasingly interconnected world from the 1950s, an integration that did not always follow the binary ideological boundaries that we have long associated with the Cold War.

Based on other travelogues, memoirs, archival material, scientific and popular journals, newspapers, fictional literature, theatre plays, poetry, songs and films, as well as interviews from Russia and several Latin American countries, I examine the cautious opening up of the USSR to the world under Nikita Khrushchev and Soviet cultural and intellectual international exchange until the disintegration of the Soviet state in 1991. Both Soviet officials and ordinary Soviet citizens were ever more confronted with an influx of ‘exotic’ people and imagery. By looking at Latin American political decision makers, intellectuals, students and the wider public, Soviet Internationalism after Stalin also reveals new insights on hitherto unstudied target groups of Soviet advances in what came to be known as the Third World. These Soviet campaigns, I argue in the book, were initially very successful in convincing many of their diverse audiences, at home and abroad, of the Soviet model as a viable alternative to Western liberal capitalism.

Historians know a fair bit about what it meant for someone from the West to live through the period of the Global Cold War. Two factors defined the general view of geopolitics: there was an ideological confrontation with the East that included a looming threat of mutual annihilation. At the same time, ordinary people experienced an ever increasing interconnected world at political, cultural and intellectual levels. Independence movements, charismatic national leaders and cruel proxy wars brought the Global South ever more to the attention of the populace in Western Europe as much as Northern America. What is less known is that similar processes played out on the Eastern side of the Iron Curtain. While late Stalinism was still a period of extreme self-isolation, one of the characteristics of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinising reforms was to reduce this isolation tremendously. For Soviet citizens, too, the Cold War now meant not only geopolitical confrontation but also increased interaction with a wider world.

Latin American music, cinema, art and literature enjoyed tremendous success with the Soviet public. Selectively imported foreign cultural products, and the adaption of Latin American motives by Soviet artists, helped entrench internationalist ideals to large parts of the Soviet population. Here, the Soviet Union’s favourite crooner Yosif Kobzon declares his love to Cuba.

Harking back to an idealised notion of pre-Stalinist socialism, Soviet politicians and intellectuals, after 1953, revived certain traditions of internationalism. Latin America, unlike other parts of the Global South with a distinct history of relations with the Soviets, became a target of Soviet advances. No longer, however, did the Kremlin propagate the violent overthrowing of governments. Moscow’s internationalists now sought to win over anti-imperialist politicians in office, intellectuals of different political leanings, and future elites as friends of the Soviet state. Through the dissemination of print media and radio shows, travelling exhibitions, and the invitation of young people, students, politicians and intellectuals, the Soviet Union after Stalin presented itself no longer as the cradle of world revolution, but as a role model of a technologically and culturally advanced, egalitarian, multicultural, and anti-imperialist modern state.

Politicised mass culture in the Soviet Union spread images of a world that was full of admiration for the USSR, and of imperialist villains who hindered the blossoming of their underdeveloped states. Propagandists could build on a widespread, and originally apolitical, fascination for exotic and adventurous outlands among large parts of the Soviet population: the most successful film ever shown in Soviet cinemas was the 1971 Mexican melodrama Yesenia, directed by Alfredo Crevenna. Over 91 million Soviet cinema goers suffered, cried and laughed through this rather turgid story of a militia man who falls in love with a racy gypsy woman.

It is a popular line of argument in Western post-Cold-War historiography that contacts with the world abroad provided for the spread of Western products and values in the USSR and thus undermined the belief in the superiority of the own system. In Soviet Internationalism after Stalin, I argue that we need to consider much more Soviet interaction with the Third World as an important integrative moment within Soviet society after Stalin. Contacts with underdeveloped countries of the Global South and the admiration for the USSR uttered by many of the visitors confirmed to many Soviet politicians, intellectuals and the wider public the ostensible superiority of their own system. Soviet Internationalism after Stalin was a source of legitimisation for the new Soviet political elite and an integrative ideational moment for Soviet society during the turmoil of de-Stalinisation and through much of the period under the rule of Leonid Brezhnev that has been labelled Stagnation.

Several thousands of young Latin Americans were invited to study at universities all over the USSR from the 1960s. Not usually affiliated with communist organisations, most of them were not uncritical about some hardships of Soviet life. Nevertheless, personal recollections reveal that the overwhelming majority remember their long years in the Soviet Union in a decidedly positive light. As a Bolivian student remembered: ‘those were the best years of my life and I miss them every day!’ And a Panamanian alumnus of Moscow State University concluded: ‘the only thing I could never accept in the Soviet Union was cold soups!’

The Latin American views of the Soviet Union presented extensively in the book shed light on the fact that the USSR looked fundamentally different from the South than from the West. While few maintained the uncritical admiration for the Soviet project we know from Western leftists of the 1920s and 30s, many Latin Americans, socialists and conservatives among them, found positive things to say about the USSR, and often still drew inspiration from it for the their own countries. This new perspective helps understand the attractive and thus cohesive factors of this system much better than the usual glance from Europe or North America. Time and again, Western observers have underlined the shortcomings and inner contradictions and conflicts within the Soviet Union to an extent that makes it difficult to understand why this system actually prevailed for so long and, through the late 1980s, enjoyed the at least passive support of the overwhelming majority of its population and the admiration of many political leaders and intellectuals in the Third World.

Historians of the Soviet Union, for the most part, have shunned approaches of ‘global history’ and have focused either on Russia’s inner history, or influences from the West. In much of what has been written on Soviet participation in the world’s integrative processes, there is a tendency to emphasise the shortcomings of the Soviet model compared to western global integration, an approach which contrasts with a core demand of global history – not to take the West as the conceptual norm. Debates on global history should thus make more allowance for encounters and exchange between the ‘Second’ and ‘Third Worlds’.

Comparisons and shared histories of different non-western countries, as I attempt in my book, put the pivotal role of the West in world history in perspective. A plethora of connections between formerly socialist states in the contemporary world take their cue from these Cold War contacts. Russia’s fortified relations with the so-called BRICS states, military and geopolitical cooperation with such countries as Nicaragua, Venezuela and Vietnam, and also the bond with the Syrian Baath Party are some of the legacies of Soviet Internationalism after Stalin that, for some time, had fallen from view because we too readily associated socialism with isolationism and global interconnectedness with free markets and liberal democracies.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.

I extremely advocate watching it and signing up for

his or her free program (click right here) NEW Now with dwell chat support!