Michael Goebel

Freie Universität Berlin

Follow on Twitter @mgoebel29

Anxieties over the possible political fallouts of African and Asian migration to Europe have a much longer history than the current refugee crisis might have you suspect. Colonial migration to interwar Paris, as I argue in Anti-Imperial Metropolis, turned into an important engine for the spread of nationalism across the French Empire. Studying the everyday lives of these migrants, in turn, might also offer a way out of the impasse that global historians currently face.

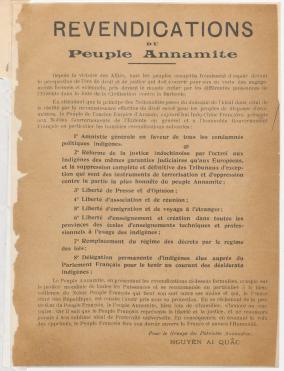

Let me begin with an anecdote that encapsulates my argument: In autumn 1919, while statesmen gathered in Paris’s upscale banlieues to redraw the political world map, local police hired a discharged Vietnamese adjutant as an undercover agent. His task was “to exercise a discrete surveillance” over a compatriot of his who had distributed leaflets entitled “The Demands of the Annamite People” among diplomats and informal spokesmen in the city’s shabbier neighbourhoods.

The newly enlisted informer took his assignment very seriously. He filed daily reports on just about every movement in the city’s Vietnamese community, producing a paper trail that can now only be traced through the National Archives in Paris and in the Colonial Archives in Aix-en-Provence.

Figuring out the author (or authors) of the incendiary leaflets in 1919 proved tricky. Police only had a name to begin with—“Nguyen Ai Quoc.” The agent noted that this was surely a byname, as it meant merely “Nguyen who loves his country,” and that several Vietnamese men who lived at the same address in the thirteenth Parisian arrondissement (6 Villa des Gobelins) had written pamphlets signed with this name, collectively calling themselves “Group of Annamite Patriots.”

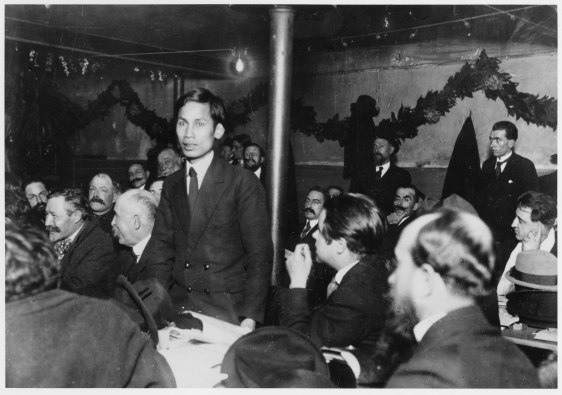

His superiors, however, became riveted to an especially bustling “intelligent young man,” who eventually professed to the agent to be the Nguyen Ai Quoc named on the document. Police henceforth considered the question of authorship settled, helping the mystery man build an ever-growing political reputation among his Parisian compatriots.

Years later, after several celebrated episodes of escaping the French authorities, the same man reinvented himself as Ho Chi Minh and shrouded his peripatetic past in ever more mysteries. As Vietnam just marked the seventieth anniversary of the 1945 declaration of independence, the cult surrounding “Uncle Ho” still appears to be on the rise.

The Local and Global of Colonial Migration

Historians have treated Ho’s alleged penning of the “Demands of the Annamite People” as the birth hour of modern Vietnamese nationalism, but have rarely paused to consider the local context in which the leaflet emerged. In spite of two decades of pleas to examine how the global manifests itself in the local and vice versa, documents such as this one are the mainstay of the intellectual and political histories of nationalism in the countries of the global south, yet their protagonists all too often appear aloof from the social world surrounding them. Attention to this local context can tell us a great deal about the global spread of nationalism in the twentieth century.

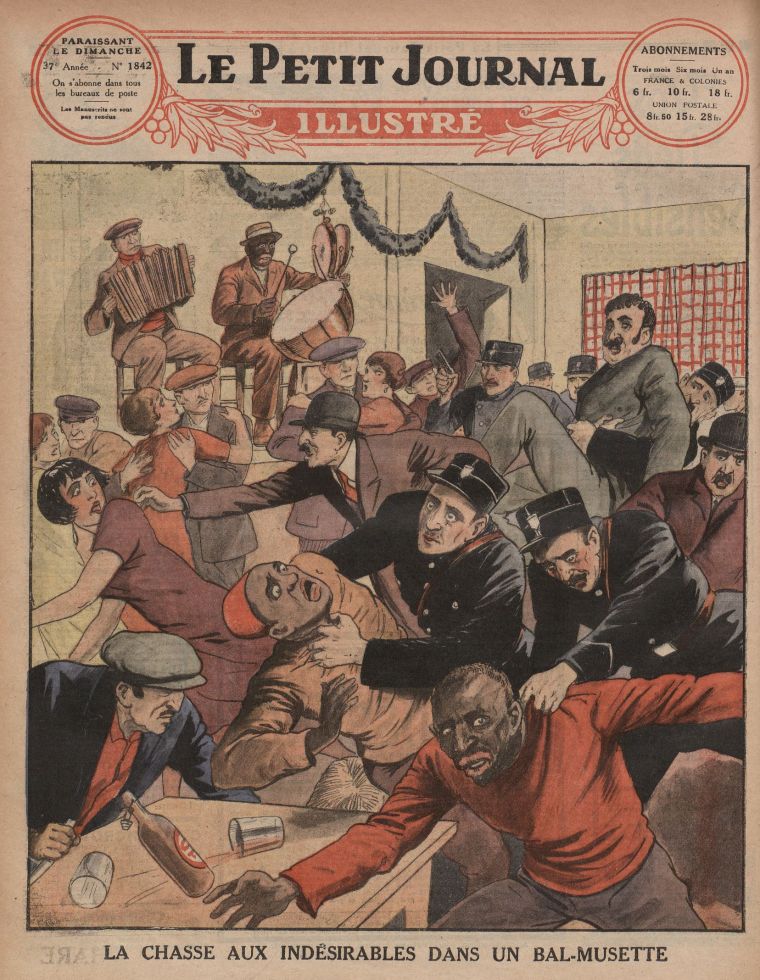

Postcolonial political and intellectual elites had spent formative stints in imperial centres such as Paris for a variety of reasons, but two stand out. The first has to do with the history of colonial migration. As France had recruited three quarters of a million colonial soldiers and workers during World War I and thereafter drew a steady trickle of labour migrants from its overseas empire, the origins of postcolonial Paris hark back one hundred years. By 1930, roughly 70,000 North African Muslims and perhaps 15,000 other colonials lived in the Paris region—almost all of them young and male. Their sojourns in the metropole familiarized them with a comparatively permissive political climate, but also highlighted the steep gap in rights that yawned between full French citizens and colonial subjects.

This inconsistency produced a plethora of migrant advocacy groups, student associations, and mutual-benefit societies replete with an ethnic press. Catering to the everyday needs and concerns of colonials in the metropole, the spokesmen of these groups also claimed to represent their disenfranchised countries of origin. Drawing this connection was far from unrealistic, as they noted that many of the problems they encountered in their lives in France were ultimately attributable to the pitfalls of a wider imperial system. In the above-cited conversation with the undercover police agent, for example, Nguyen Ai Quoc constantly jumped between local concerns, such as a cemetery for fallen Vietnamese soldiers in a Paris suburb, and global geopolitics, such as Japan’s or France’s territorial gains at the negotiation table of the peace conference.

The “Demands of the Annamite People” typically arose out of a group effort. The pattern was similar across different communities. North Africans and West Africans, Malagasies and Antilleans, all had their own ethnic associations and periodicals in Paris, which claimed greater rights—and sometimes even national independence—for themselves. Likewise, Chinese worker-students founded welfare societies and local communist party branches, from which later leaders such as Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping hailed. Like the “Annamite Patriots,” they gathered at particular Parisian addresses, to which newcomers were pulled upon their arrival in the French capital. Steady back-and-forth movements tied specific places of origin with specific places in the Parisian cityscape, as is common for migratory processes in general.

The Cosmopolitanism of Interwar Paris

The second reason was that the unique cosmopolitan environment of interwar Paris—and especially the Latin Quarter—facilitated ideological pollination across ethnic boundaries. “Monsieur Nguyen Ai Quoc,” the undercover informer reported on New Year’s Eve 1920, “bases himself on everything the Koreans do. He has almost exactly followed the plan of the Korean rebels.” The Vietnamese activist, meanwhile, compared his people’s fate to that of his Parisian neighbours. “The Annamites wish nothing but to see France treat them like other peoples, at least like Tunisians and Algerians,” he allegedly said once.

With the support of the French Communist Party, which he had joined at its founding congress in Tours in 1920, the later Ho Chi Minh went on to found a political group called Intercolonial Union, which specialized in this kind of extrapolating from one colonial context to another. Apart from the “Annamite Patriots,” Antillean lawyers who lobbied for the extension of French citizenship to Malagasy war veterans joined the Intercolonial Union.

Here again, rights differentials between colonials of different origins fanned mutual learning curves and the transmission of particular political demands—most notably the call for national sovereignty—from one context to another. The Intercolonial Union churned out some of the leading anticolonialists from across the French Empire, as well as key speakers at the 1927 Conference of the League against Imperialism, which is now widely considered as an antecedent of the Bandung Conference sixty years ago.

Conclusion

Apart from telling us something about the genealogy of Third World nationalism, the history of anti-imperialism in interwar Paris also speaks to the dilemmas of the growing field of global history that are currently being debated. In order to avoid the risk of diminishing returns through imperial overstretch, of which David Bell warns us, the kind of urban social history I propose offers a way of mooring a question about “motors of change”—here the global spread of nationalism—in the local experience of concrete and identifiable individuals. It may thus serve as an antidote to taking too literally the “global” in “global history.”

Professor Michael Goebel is the author of Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third World Nationalism (Cambridge University Press, 2015). Be sure to also watch this interview with the author.

5 thoughts on “A Parisian Ho Chi Minh Trail: Writing Global History Through Interwar Paris”

Comments are closed.