Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter/X @MWPalen

From how Shōgun exposes the brutal realities of colonization to how ‘Made in China’ became American gospel, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history.

Shōgun Exposes the Brutal Realities of Colonization

Joe Mayall

Jacobin

In just a few weeks since its debut, FX’s miniseries Shōgun has thrilled its audience and become the #1 streamed show in America. Based on the novel by James Clavell, Shōgun tells the story of a power struggle for control of feudal Japan when Europeans make first contact with the island. The Portuguese and Dutch bring mystery, guns, Old World religious conflict, and most nefariously, colonial ambitions to the newly discovered nation, shaking an already unstable political structure.

While the show’s palace intrigue and warring factions are sure to scratch the itch of anyone missing Game of Thrones or Succession, the historical setting offers something unique: it provides an interesting window into the process of colonization, which is rarely shown on screen. While there’s no shortage of movies and television featuring the struggle underway between colonized and colonizers (Killers of the Flower Moon, The Expanse), seldom are audiences treated to a dramatization of imperialism’s inaugural moments. As Shōgun is set in the period of first contact between Europe and Japan, it shows the colonial process play out through the eyes of the indigenous population. [continue reading]

Nuclear Fatalism in ‘Oppenheimer’ Is a Dead End

Jonathan R. Hunt

Foreign Policy

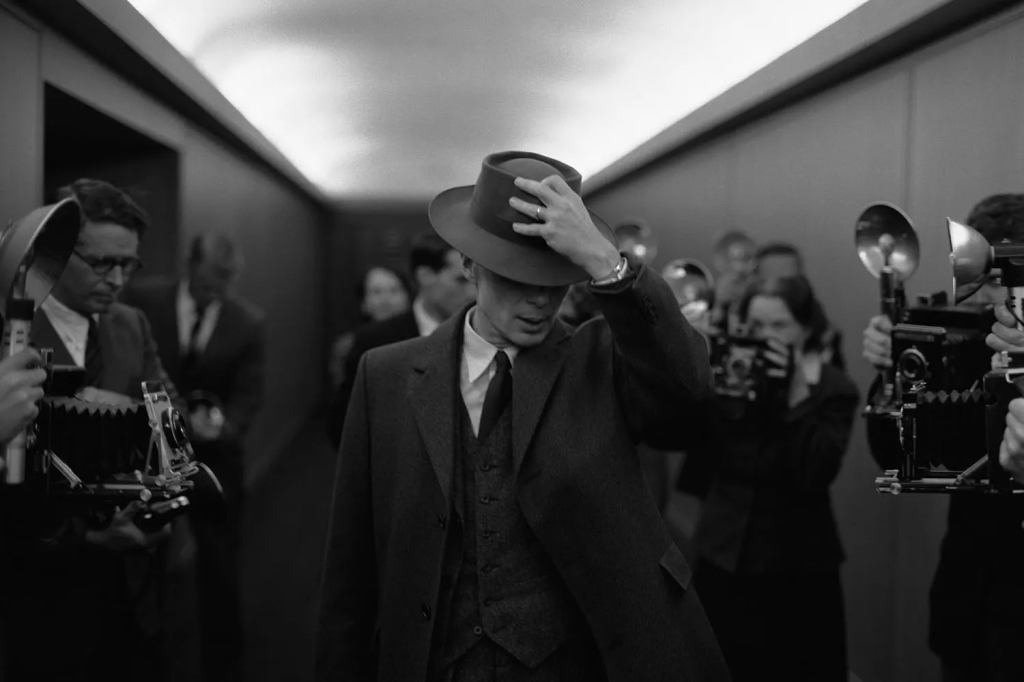

In a key scene of Christopher Nolan’s biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the weapons laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, addresses a crowd of foot-stamping scientists, engineers, and staff. The father of the atomic bomb exudes an uncharacteristic ferocity: “The world will remember this day. It’s too soon to determine what the result of the bombing are, but I’ll bet the Japanese didn’t like it. I’m so proud, so proud of what you have accomplished. I just wish we’d had it in time to use against the Germans.”

Filmgoers know what comes next—the blinding flash, the deafening roar, the carbonized corpse—victory turned to ashes in the cheering mouths of those who forged an artificial sun. Oppenheimer is many things: a reminder that serious movies can earn billions of dollars, a testament to the power of biography to serve as allegory, a memorial to those who tapped the secret dynamo in the spaces between protons. Now, it has won the Oscar for Best Picture. But the film leaves out a core part of Oppenheimer’s story. [continue reading]

The Many Faces of Viet Thanh Nguyen

Mari Uyehara

Nation

Viet Thanh Nguyen was groaning. He couldn’t help it. He had already sat through a sermon conducted in a rarefied Vietnamese dialect that he couldn’t understand. The congregation had risen and sat down, risen and sat down. They had beat their breasts to rattle their souls and purify their hearts.

A slight young man with shaggy black hair, Nguyen was nearly indistinguishable from a sea of hundreds of black and gray heads of hair assembled in the packed congregation. The majority of the congregants at St. Patrick’s Church in San Jose, Calif., were refugees, just like his family, who had fled the country at the height of the war in Southeast Asia. [continue reading]

Students & Afro-Asian Solidarity

Wildan Sena Utama

History Workshop

The Bandung Conference of 1955 in Indonesia is widely recognised as a landmark moment that inspired Asians and Africans to carve out a transnational network based on intercontinental solidarity in the pursuit of a decolonised world. In a lesser known meeting, one year later, hundreds of students from twenty-seven Asian and African countries gathered in Bandung, the city dubbed by India’s Jawaharlal Nehru as ‘the capital of Asia-Africa’, for the Afro-Asian Students’ Conference (AASC). Willard Hanna, an American observer of the event, referred to the AASC as ‘The Little Bandung Conference’ – because it was like that earlier meeting in terms of location, model and purpose, only smaller in scale. Yet, the AASC was not just a miniature version of the Bandung Conference that preceded it. It can be understood in its own right as a site in which students played a key role in forging internationalist solidarity in the post-war world.

The students from Asia and Africa that built such solidarities have been the focus of my research on the struggles for independence and decolonisation in the mid-twentieth century. These students were often backed by heads of state from the Afro-Asian world, and their work often complemented the decolonial aspirations of emerging nations. At the same time, they were instrumental in initiating an era of transnational cooperation on social, political, economic, cultural and women’s issues. What, then, did decolonisation mean to these students? The story of the AASC shows some of the deliberations about the meaning and scope of decolonisation taking place within the project of Afro-Asianism. [continue reading]

How ‘Made in China’ Became American Gospel

Elizabeth O’Brien Ingelson

Foreign Policy

On Oct. 25, 1976, U.S. businessman Charles Abrams traveled to New York City’s South Street Seaport to welcome a ship loaded with Chinese vodka. This was, according to Abrams, the first time the liquor had been commercially imported from China since 1949. Abrams turned this moment into an elaborate marketing event. The port was festooned with a vinyl balloon replica of a bottle of vodka the height of a three-story building. Swaying on the windy dock, the vodka-shaped balloon towered over a group of around 80 people, including New York’s ports and terminals commissioner, Louis F. Mastriani, who had gathered to celebrate the imports. Once the cases of vodka had been unloaded, the group convened at a Chinese restaurant where, the China Business Review reported with a wink, “the vodka and viands quickly warmed up the guests.”

Abrams was part of a new generation of U.S. businesspeople who began to trade with China after more than 20 years of Cold War isolation. Fascination, hope, excitement, frustration: Emotions guided their decisions as much as hardheaded economics—often more so. Working alongside businesspeople in China, they began to see something new in the China market. [continue reading]

You must be logged in to post a comment.