Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Richard Toye, University of Exeter

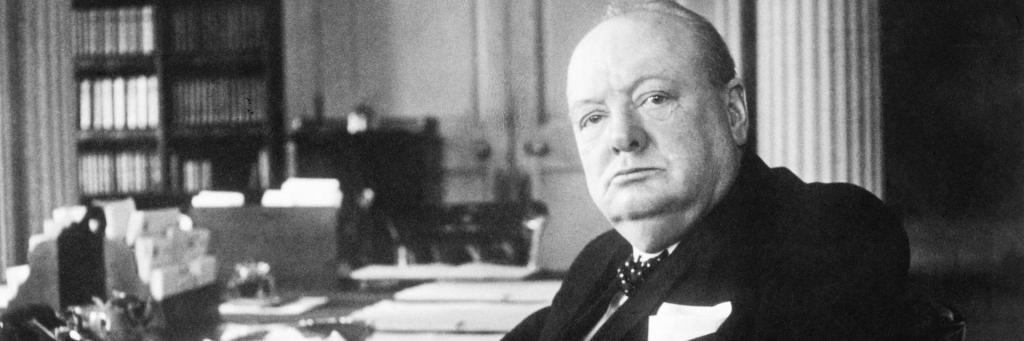

When Donald Trump criticised Keir Starmer for failing to sufficiently support American and Israeli operations against Iran, he did so with a historical flourish. “This is not Winston Churchill that we’re dealing with,” he complained.

The implication was clear: Churchill would have stood shoulder to shoulder with Washington in a confrontation with Tehran. The remark invites an obvious question: what would Churchill have made of war with Iran?

The answer is not as straightforward as Trump’s comparison suggests. Churchill’s record shows a mixture of hawkish rhetoric, strategic caution and a constant concern with maintaining Anglo-American unity. Far from embodying a simple instinct for confrontation, he tended to see war and diplomacy as inextricably linked.

Continue reading “What would Winston Churchill make of war with Iran?”

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Mitchel Stuffers, PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter & Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter

Anton Adriaan Mussert, the leader of the Dutch fascist National Socialist Movement(Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, NSB), took a 2-month trip to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) in 1935. While there, he agreed to an interview by the colony’s nationalist newspaper Pemandangan, wherein Mussert, remarkably, sought to sell the empire to its anticolonial-leaning readership.

I uncovered the interview while researching my PhD, which integrates imperial & colonial studies and comparative fascist studies by examining how organisations like the Dutch National Socialist Movement(NSB) built, justified, and executed their visions of fascist international worldbuilding. It also draws on Holocaust & Genocide Studies and Intellectual History to gain a more holistic overview of its origins and aims.

Over the last year and a half, I engaged with materials not only from the Netherlands but also pieces from some of its former colonies, like Indonesia, to engage with those inquiries.

Dutch colonial rule over Indonesia, especially before the outbreak of World War Two, was of enough interest to the NSB that its leader had decided to visit it and create an inter-imperial branch to operate from it. The NSB’s efforts to establish a foothold in the colony have led to various arguments among historians. Some claim that Mussert sought to use the Dutch East Indies as a steady stream of funds, and that the Indonesian NSB operated as a mere extension of the motherland’s metropolitan interests.[1] Another scholar reasoned that the NSB had held an “inclusive culturalist notion” of pan-imperial cooperation in its outlook on the colonies, whereby the organisation at large was genuinely impacted, until ethnonationalist chauvinism eventually ended it.[2] The existence of an interview wherein Anton Mussert was transcribed into Indonesian, rather than Dutch, thereby sways us to lean towards the latter hypothesis and examine its peculiarities, wherein an appeal to the colony may reveal its pre-war PR strategies.

Examinations on the NSB more broadly start with insightful works such as those by Edwin Klijn and Robin te Slaa, which, when discussing the NSB’s colonial & imperial aspects, argue that the urge for Lebensraum (Living space) was essentially nullified for the Dutch fascists due to the presence of the colonies before World War Two.[3] More recent historiography includes Tessel Pollman,[4] Jennifer Foray,[5] Geraldien von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel,[6] and Nathaniël Kunkeler.[7] However, it was a note in an older work, from 1968, that led to this short article. Simon L van der Wal briefly mentioned the existence of an interview with the NSB’s Leader, Anton Adriaan Mussert, by a leading Indonesian newspaper;[8] one with anti-colonial, pro-independence leanings.[9] The existence of this interview thereby challenges the way we understand the outreach of ultranationalist groupings to their non-white audiences. It moves us to ask how inter-imperial organisations like the NSB appealed to the wider sphere of colonised subjects, beyond the organisation’s perceived exclusivist dimensions, as has widely been the case in popular memory in the Netherlands following the NSB’s downfall.

Continue reading “How a Dutch Fascist Marketed the Empire in Pemandangan: Mussert’s Indonesian Interview”

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Dr Kalathmika Natarajan, a Lecturer in Modern South Asian History at the University of Exeter, recently sat down for a Forum interview to discuss her exciting new book, Coolie Migrants, Indian Diplomacy: Caste, Class, and Indenture Abroad, 1914-67 (London: Hurst, 2025 and New York: Oxford University Press, 2026). Dr Natarajan’s CIGH book launch is Wed. Jan. 28 from 3:30-5pm. Click here for further details of the book launch.

This book began as a PhD thesis at the University of Copenhagen in 2015 – it started off as a doctoral thesis focused on postcolonial ties between Britain and India but thankfully evolved into a larger project that explored the ways in which migration shaped Indian diplomatic history. I wanted to go beyond the overwhelming focus on high politics in this field by drawing on the critical, postcolonial turn in new diplomatic history. This took me to a whole host of archives that made it abundantly clear how Indian diplomacy was irrevocably shaped by the histories and legacies of indenture and labour migration – most evident in the anxieties of caste elites over the figure of the ‘coolie’ migrant. Such a framework helped centre caste as an essential category that shaped Indian imaginations of the international realm and those best suited to traverse it. This also enabled me to write a bottom-up history about how labour migrants shaped diplomacy, rather than simply being recipients and ‘problems’ of diplomacy.

Continue reading “Coolie Migrants, Indian Diplomacy: A CIGH book interview with Dr Kalathmika Natarajan”

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Neville Morley, University of Exeter

In his speech to this year’s World Economic Forum at Davos, Canadian prime minister Mark Carney mourned the demise of international cooperation by evoking an authority from ancient Greece.

“It seems that every day we’re reminded that we live in an era of great power rivalry, that the rules-based order is fading, that the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must. And this aphorism of Thucydides is presented as inevitable, as the natural logic of international relations reasserting itself.”

Journalists and academics from Denmark, Greece and the United States have quoted the same line from the ancient Greek historian when discussing Donald Trump’s demand for Greenland. It is cited as inspiration for his adviser Stephen Miller’s aggressive foreign policy approach, not least towards Venezuela.

In blogs and social media, the fate of Gaza and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have been interpreted through the same frame. It’s clearly difficult to contemplate today’s world and not react as W.H. Auden did to the collapse of the old order in 1939: “Exiled Thucydides knew.”

The paradox of the “strong do what they can” line is that it’s understood in radically different ways. On the one hand, it’s presented as a description of the true nature of the world (against naive liberals) and as a normative statement (the weak should submit).

On the other hand, it’s seen as an image of the dark authoritarian past we hoped was behind us, and as a condemnation of unfettered power. All these interpretations claim the authority of Thucydides.

That is a powerful imprimatur.

Thucydides’ insistence on the importance of seeking out the truth about the past, rather than accepting any old story, grounded his claim that such inquiry would help readers understand present and future events.

As a result, in the modern era he has been praised both as the forerunner of critical scientific historiography and as a pioneering political theorist. The absence of anything much resembling theoretical rules in his text has not stopped people from claiming to identify them.

The strong/weak quote is a key example. It comes from the Melian dialogue from Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. In 416BC, an Athenian force arrived at the neutral island of Melos and demanded its surrender. The Melian leaders asked to negotiate, and Thucydides presents a fictional reconstruction of the subsequent exchange.

The quote comes from the beginning, when the Athenians stipulated that they would not claim any right to seize Melos, other than the power to do so, and conversely would not listen to any arguments from principle. “Questions of justice apply only to those equal in power,” they stated bluntly. “Otherwise, such things as are possible, the superior exact and the weak give up.”

Within modern international relations theory, this is sometimes interpreted as the first statement of the realist school of thought.

Scholars like John Mearsheimer claim that Thucydides identified the basic principle of realist theory that, in an “anarchic” world, international law applies only if it’s in powerful states’ strategic interest, and otherwise might makes right. The fate of the Melians, utterly destroyed after they foolishly decided to resist, reinforces the lesson.

But these are the words of characters in Thucydides’ narrative, not of Thucydides himself. We cannot simply assume that Thucydides believed that “might makes right” is the true nature of the world, or that he intended his readers to draw that conclusion.

The Athenians themselves may not have believed it, since their goal was to intimidate the Melians into surrendering without a fight. More importantly, Thucydides and his readers knew all about the disastrous Athenian expedition to Sicily the following year, which showed the serious practical limits to the “want, take, have” mentality.

So, we shouldn’t take this as a realist theoretical proposition. But if Thucydides intended instead simply to depict imperialist arrogance, teach “pride comes before a fall”, or explore how Athenian attitudes led to catastrophic miscalculation, he could have composed a single speech.

His choice of dialogue shows that things are more complicated, and not just about Athens. He is equally interested in the psychology of the “weak”, the Melians’ combination of pleading, bargaining, wishful thinking and defiance, and their ultimate refusal to accept the Athenian argument.

This doesn’t mean that the Melian arguments are correct, even if we sympathise with them more. Their thinking can be equally problematic. Perhaps they have a point in suggesting that if they give in immediately, they lose all hope, “but if we resist you then there is still hope we may not be destroyed”.

Their belief that the gods will help them “because we are righteous men defending ourselves against aggression”, however, is naive at best. The willingness of the ruling clique to sacrifice the whole city to preserve their own position must be questioned.

The back and forth of dialogue highlights conflicting world views and values, and should prompt us to consider our own position. What is the place of justice in an anarchic world? Is it right to put sovereignty above people’s lives? How does it feel to be strong or weak?

It’s worthwhile engaging with the whole episode, not just isolated lines – or even trying to find your own way through the debate to a less bad outcome.

The English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, introducing his classic 1629 translation, noted that Thucydides never offered rules or lessons but was nevertheless “the most politic historiographer that ever writ”. Modern readers have too often taken isolated quotes out of context, assumed that they represent the author’s own views and claimed them as timeless laws. Hobbes saw Thucydides as presenting complex situations that we need to puzzle out.

It’s remarkable that an author famed for his depth and complexity gets reduced to soundbites. But the contradictions in how those soundbites are interpreted – the way that Thucydides presents us with a powerful and controversial idea but doesn’t tell us what to think about it – should send us back to the original.![]()

Neville Morley, Professor in Classics, Ancient History, Religion, and Theology, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

All seminars take place on Wednesdays 3.30pm-5.00pm in person in Room B310, Amory, unless otherwise noted, with the option to join remotely. Reminders, links, and abstracts will be sent a week in advance of each seminar to the CIGH mailing list. To be added, please email Chris and Beccy at c.w.sandal-wilson@exeter.ac.uk and r.williams2@exeter.ac.uk.

WEDNESDAY 28 JANUARY [Week 3] Coolie Migrants, Indian Diplomacy

Join us to celebrate the launch of Coolie Migrants, Indian Diplomacy by our very own Kalathmika Natarajan. Drawing on multi-sited archival research, Coolie Migrants, Indian Diplomacy reimagines the history of diplomacy in independent India by putting labour migration at the heart of the story. Co-hosted with the South Asia Centre.

WEDNESDAY 25 FEBRUARY [Week 7] Explaining Famine in the British Empire

Join us to celebrate the launch of Explaining Famine in the British Empire, by our very own John Lidwell-Durnin. Focusing on the famines and food shortages that struck India and Britain in the late eighteenth century, Explaining Famine tracks the rise of scientific efforts to understand and solve food insecurity in the British empire.

WEDNESDAY 18 MARCH [Week 10] Fascism in India

Join us to hear Luna Sabastian (Northeastern University, London) speak about her new book, Fascism in India, which offers an innovative new intellectual history of the emergence of a distinctive brand of fascist thought in India under colonial rule. Co-hosted with the South Asia Centre.

WEDNESDAY 25 MARCH [Week 11] Postgraduate Research Symposium

As always, we’ll see out the term on a high note: join us as post-graduate researchers working on Imperial and Global History at Exeter share their work in progress.

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Call for applications: December 2, 2025 – March 31, 2026

This course focuses on the growing interdisciplinary field of Linguistic Landscapes (LL), which traditionally analyses “language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings”, as they usually occur in urban spaces.

More recently, LL research has evolved beyond studying only verbal signs into the realm of semiotics, thus extending the analytical scope into the multimodal domain of images, sounds, drawings, movements, visuals, graffiti, tattoos, colours, smells as well as people.

Students will be informed about multiple aspects of modern LL research including an overview of different types of signs, their formal features as well as their functions.

Faculty

Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven (Coordinator)

Richard Toye, University of Exeter (Coordinator)

Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice

Bert Oben, KU Leuven

Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter

Michela Maguolo, Independent researcher

Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

Guest lecturers

Alberto Toso Fei, Director Urbs Scripta (tbc)

Desi Marangon, Director Urbs Scripta

Who is it for?

Applications are welcome from current final year Undergraduates (finalists, BA3), MA and MPhil/PhD Students in Linguistics, Sociology, Classical Studies, (Business) Communication Studies, History, Cultural Studies, Political Studies, Translation Studies or any other related discipline.

You must be logged in to post a comment.