Editor’s Note: In the weeks leading up to the new year, please help us remember 2018 at the Imperial & Global Forum by checking out the past year’s 10 most popular posts.

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

US Economic Imperialism within a British World System

Historians have been busy chipping away at the myth of the exceptional American Empire, usually with an eye towards the British Empire. Most comparative studies of the two empires, however, focus on the pre-1945 British Empire and the post-1945 American Empire.[i] Why this tendency to avoid contemporaneous studies of the two empires? Perhaps because such a study would yield more differences than it would similarities, particularly when examining the imperial trade policies of the two empires from the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century.

For those imperial histories that have attempted such a side-by-side comparison, the so-called Open Door Empire of the United States is depicted as having copied the free-trade imperial policies of its estranged motherland by the turn of the century; these imitative policies reached new Anglo-Saxonist heights following US colonial acquisitions in the Caribbean and the Pacific from the Spanish Empire in 1898, followed closely by the fin-de-siècle establishment of the Anglo-American ‘Great Rapprochement’.[ii]

Gallagher and Robinson’s 1953 ‘imperialism of free trade’ thesis—which explored the informal British Empire that arose following Britain’s unilateral adoption (and at times coercive international implementation) of free-trade policies from the late 1840s to the early 1930s—has played a particularly crucial theoretical role in shaping the historiography of the American Empire. In The Tragedy of American Diplomacy(1959), William Appleman Williams provided the first iteration of the imitative open-door imperial thesis, wherein he explicitly used the ‘imperialism of free trade’ theory in order to uncover an American informal empire. ‘The Open Door Policy’, Williams asserted, ‘was America’s version of the liberal policy of informal empire or free-trade imperialism’.[iii] The influence of Williams’s provocative thesis led to the creation of the most influential school of US imperial history—the ‘Wisconsin School’—which would continue in its quest to unearth American open-door or free-trade imperialism for decades to come.[iv] As a result, the contrasting ways in which the American Empire grew in the shadow of the British Empire have largely remained hidden. [continue reading]

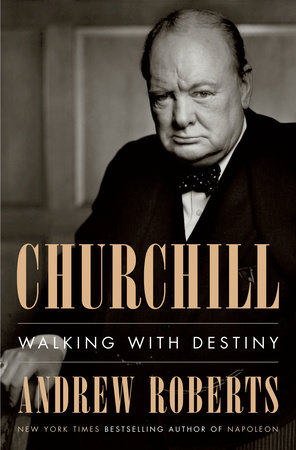

On April 9, 1994, the cover of the Spectator boasted a colourful cartoon that depicted Winston Churchill sticking up two fingers to a boatload of Caribbean migrants – “the Windrush generation”, as we would now call them. Inside was an article by Andrew Roberts (who had previously made a name for himself as a biographer of Lord Halifax) which labelled Churchill as an ideological racist. “For all his public pronouncements on ‘The Brotherhood of Man’ he was an unrepentant white – not to say Anglo-Saxon – supremacist”, Roberts wrote. Moreover, “for Churchill, negroes were ‘niggers’ or ‘blackamoors’, Arabs were ‘worthless’, Chinese were ‘chinks’ or ‘pigtails’, and other black races were ‘baboons’ or ‘Hottentots’.”

On April 9, 1994, the cover of the Spectator boasted a colourful cartoon that depicted Winston Churchill sticking up two fingers to a boatload of Caribbean migrants – “the Windrush generation”, as we would now call them. Inside was an article by Andrew Roberts (who had previously made a name for himself as a biographer of Lord Halifax) which labelled Churchill as an ideological racist. “For all his public pronouncements on ‘The Brotherhood of Man’ he was an unrepentant white – not to say Anglo-Saxon – supremacist”, Roberts wrote. Moreover, “for Churchill, negroes were ‘niggers’ or ‘blackamoors’, Arabs were ‘worthless’, Chinese were ‘chinks’ or ‘pigtails’, and other black races were ‘baboons’ or ‘Hottentots’.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.