Mitchel Stuffers

Assistant Editor at CIGH Exeter & PhD Candidate in History, University of Exeter

Category: Imperial & Global History

Autumn Term Research Seminar Schedule

Centre for Imperial and Global History

Research Seminars

~ Autumn 2025 ~

All seminars take place on Wednesdays 3.30pm-5.00pm in person in Amory B310 unless otherwise noted, with the option to join remotely. Reminders, links, and abstracts will be sent a week in advance of each seminar to the CIGH mailing list. To be added, please email Chris and Beccy at c.w.sandal-wilson@exeter.ac.uk and r.williams2@exeter.ac.uk.

WEDNESDAY 1 OCTOBER [Week 2] Welcome (Back) Social

Join us in the Amory Senior Common Room for an informal gathering to mark the start of the academic year, welcome new researchers, and catch up with old friends.

WEDNESDAY 8 OCTOBER [Week 3] Parting Gifts of Empire: Book Talk

Join us for a talk by Esmat Elhalby (Toronto) around his forthcoming book, Parting Gifts of Empire: Palestine and India at the Dawn of Decolonisation. This event is co-hosted with South Asia Centre and the European Centre for Palestine Studies. NB: This event will take place 2.30-4.30pm in Lecture Theatre B, Streatham Court.

WEDNESDAY 22 OCTOBER [Week 5] Legacies of Devon Slavery Connections

At this event, members of the Legacies of Devon Slavery Connections Group will be sharing the work that they have been doing to explore Devon’s local connections to slavery, and their insights into sources and archives for doing this kind of research.

WEDNESDAY 5 NOVEMBER [Week 7] Meet our visiting researchers!

Join us to learn more about the exciting research our visiting doctoral and post-doctoral research colleagues are doing here at Exeter. Saloni Verma and Nazlı Songulen will present on their ongoing projects.

WEDNESDAY 3 DECEMBER [Week 11] The Bonds of Freedom: Book Talk

Join us to hear Jake Subryan Richards (LSE) speak about his new book, The Bonds of Freedom, which tells the forgotten story of people seized from slave ships by maritime patrols, “liberated”, then forced into bonded labour between 1807 and 1880. NB: This event will take place in Amory C417.

WEDNESDAY 10 DECEMBER [Week 12] Postgraduate Research Symposium

As always, we’ll see out the term on a high note: join us as post-graduate researchers working on Imperial and Global History at Exeter share their work in progress.

Signs of Resistance: Linguistic Landscapes and Urban Tensions in Santa Marta, Venice

Berizzi Mariachiara[1], Boam Olivia[2], Fourie Nicholas Charles[3], Pizarro Jacinto Laura[4], Yücel Dinç Fatma[5]

‘Linguistic Landscapes‘, Venice International University Summer School 2025

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven (Coordinator); Richard Toye, University of Exeter (Coordinator); Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Iuav, University of Venice; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

In Santa Marta, a quiet Venetian district, the city itself becomes a text: walls, streets, and public spaces speak through signs, graffiti, and infrastructures that reveal five interwoven themes: Anti-tourism, Transport & Mobility, Multilingualism & Symbolic Resistance, Government & Authority, and Prison as an Edge. From anti-tourism sentiments to the symbolic tensions of incarceration, our investigation examines how language, infrastructure, and public space interact to shape meaning and mobility. As shown in Figure 1, which provides a satellite view of Venice highlighting key landmarks and mobility nodes, our study is grounded in the spatial reality of the city. We begin by analysing local resistance to mass tourism, then move through the spatial logic of transport hubs like Piazzale Roma. We further consider multilingualism and graffiti as forms of symbolic resistance, explore the role of governance in shaping visibility and authority, and finally, interpret the Santa Maria Maggiore prison as both a physical and discursive edge.

‘This country had a great empire’: The Nuances and Limits of the Rhetorical Premiership in Using the Imperial Past

Shagnick Bhattacharya

University of Exeter

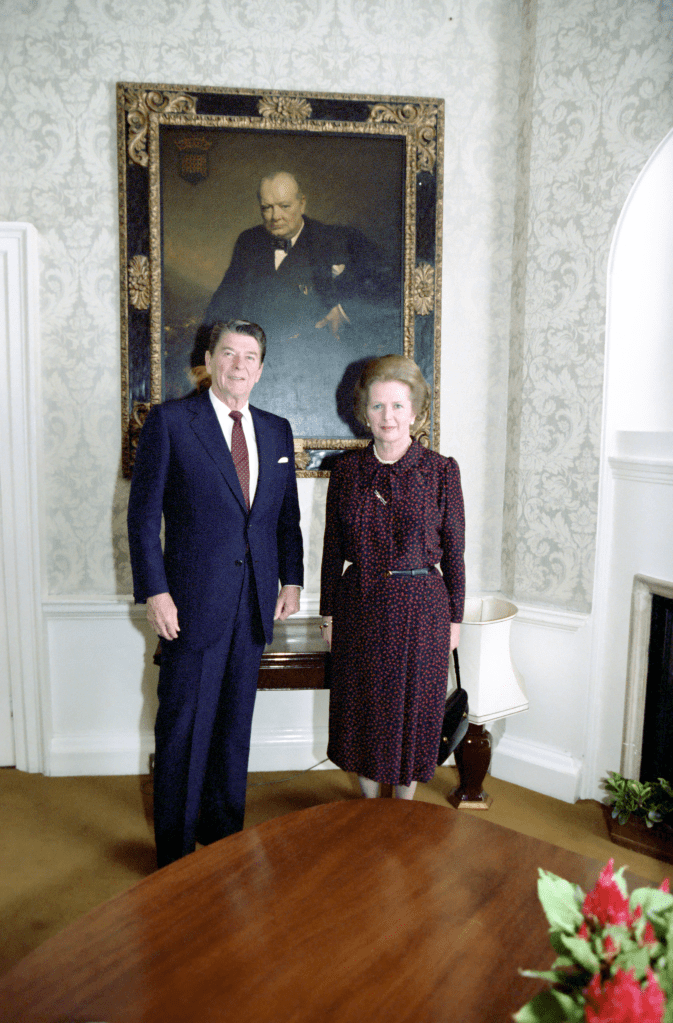

This article proposes that there were nuances and limits to Cold War-era British Prime Ministers’ use and abuse of the country’s imperial past to influence policy, shape national identity, and navigate international relations. That Prime Ministers’ use of public speeches to further their political agendas should receive greater academic attention was first proposed by Richard Toye[1] over a decade ago, and has currently taken the shape of an active research project[2] focussing specifically upon imperial rhetoric (titled ‘Talking Empire’—not to be confused with the CIGH’s podcast series!) led by Christian Damm Pedersen at the Syddansk Universitet, having recently received funding from the Carlsberg foundation.

Using contemporary newspaper reports from across Britain as sources, my intervention here will be on two counts: firstly, by showing how Margaret Thatcher used the legacy and memory of Churchill in her rhetoric as a surrogate for referring to the imperial past (rather than directly mentioning the Empire in the first place) in order to publicly talk about her desired economic policies; secondly, by noting how any rhetorical premiership’s reliance on the imperial past could also be turned against the premier by their political opposition (and not even necessarily by anti-imperialists) in an attempt to strip it of its usefulness as a political resource for the former.

Continue reading “‘This country had a great empire’: The Nuances and Limits of the Rhetorical Premiership in Using the Imperial Past”Striking a balance between residents and tourists? The Linguistic Landscape of Santa Maria Formos

Beatrice Gervasi, Katarzyna Jonkisz, Meng Hao, Sabeth Malfliet, and George Ellis

Students of ‘Linguistic Landscapes‘, Venice International University Summer School 2025

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven (Coordinator); Richard Toye, University of Exeter (Coordinator); Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Iuav, University of Venice; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

Our case study of Venice for the ‘Linguistic landscapes: signs and symbols’ summer school was centred around the storied neighbourhood of Santa Maria Formosa. This area boasts a historic Basilica, the Fondazione Querini Stampalia library and a new art installation of 2 lions and 2 lionesses which is intended to promote public interaction with art and celebrate Venetian pride. In short, this area offers a lot culturally and historically. This is strongly evident when walking down the side streets. During our first excursion, our group got the immediate sense that this was a residential area that had developed a strong tourist population due to its historical significance and geographic location (en route to the Rialta bridge).

We were fortunate in the sense that this region of Venice was not a particularly large one, being measured at 0.0072km^2. However, this did not mean that our investigations were without challenge. The geography of this area (a seeming thoroughfare for tourist populations) led to difficulties in photo collation. This combined with the high-content-per-area (a total of 73 relevant primary photos) and the labyrinthine streets led to our group having an abundance of data and difficulties delimiting our data set and research question. To overcome this, we adopted a thematic approach which split our data set into three relevant points for discussion: action flows, multilingualism and polyfunctionality. We then used relevant semiotic and anthropological studies (for example Landry and Bourhis 1997, Scollon and Scollon, 2003) to dissect the data set and apply a linguistic landscapes lens with the end goal of finding out whether Santa Maria Formosa is a healthily functioning neighbourhood or another victim of the increasing globalization faced all over the western world.

Continue reading “Striking a balance between residents and tourists? The Linguistic Landscape of Santa Maria Formos”Venice in absentia: A linguistic landscape of San Francesco della Vigna

Hualing Zhai[1], Quinten Heymans[2], Bartolomeo Perazzoli[3], Sophie Paynter[4], Alice Wadsworth[5]

Students of ‘Linguistic Landscapes‘, Venice International University Summer School 2025

Faculty: Kurt Feyaerts, KU Leuven (Coordinator); Richard Toye, University of Exeter (Coordinator); Matteo Basso, Iuav University of Venice; Geert Brône, KU Leuven; Claire Holleran, University of Exeter; Eliana Maestri, University of Exeter; Michela Maguolo, Iuav, University of Venice; Paul Sambre, KU Leuven

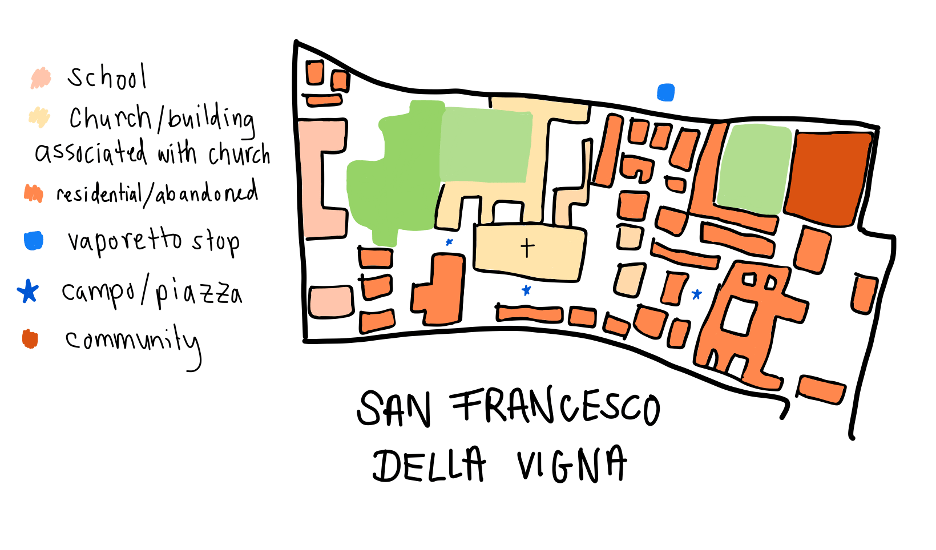

Introducing San Francesco della Vigna

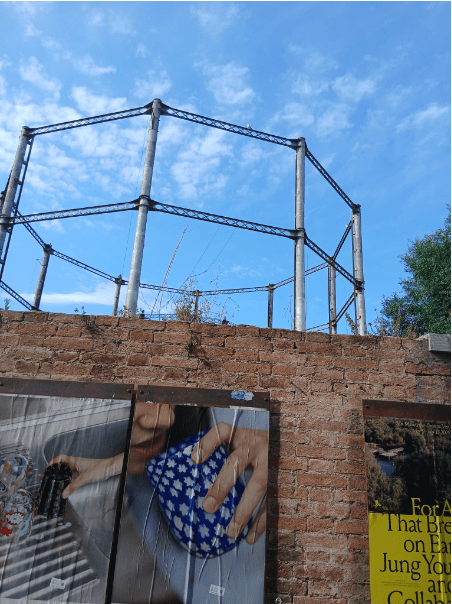

San Francesco della Vigna (later also SFdV), located on the northeastern edge of Venice, presents a sharp contrast to the city’s typical romantic image. The area may feel, in some ways, stuck in time, with the campo (the Venetian equivalent of a piazza) overlooked by a large gasholder (image 3) on one side, and the beautiful if somewhat imperious 16th-century church of San Francesco della Vigna (image 4). Our group, as part of the 2025 VIU Linguistic Landscapes summer school, explored this working-class neighbourhood focusing on the themes of presence and absence. At first, the area seems quiet and almost forgotten, with few signs of life such as shops, cafés, or passersby. However, through exploring the linguistic and semiotic landscapes and the soundscape of the area, we found a quietly strong local identity to be bubbling away beneath the seemingly barren surface.

We were lucky enough to explore every inch of the isola, and the walls were deep in conversation with the neighbourhood and with each other. So perhaps this work, and any work of mapping out a linguistic landscape, can be considered a kind of ethical ‘eavesdropping’. We observed- and listened- from outside but we were also able to conduct a few interviews as part of our research. Interviews with residents highlighted ongoing gentrification and local feelings of resistance. One construction worker noted that scaffolding usually indicates Airbnb renovations, reflecting economic and demographic changes.

Continue reading “Venice in absentia: A linguistic landscape of San Francesco della Vigna”The Anti-Imperialism of Economic Nationalism: Transimperial Protectionist Networks in Anticolonial Ireland, India, and China

Marc-William Palen

University of Exeter

Cross-posted from the Transimperial History Blog

Beginning around 1870, the protectionist US Empire sparked a global economic nationalist movement that spread like wildfire across the imperial world order. Late-nineteenth-century expansionists within the Republican Party got things started in the 1860s when they enshrined what was then known as the “American System” of protectionism — high protective tariffs coupled with subsidies for domestic industries and internal improvements — as official US imperial economic policy. By 1900, American System advocates within the GOP carved out a protectionist colonial US empire to insulate itself from the real and perceived imperial machinations of the more industrially advanced British, who had unilaterally embraced a policy of free trade in the 1840s.[1] As I explore in my new book, Pax Economica: Left-Wing Visions of a Free Trade World (Princeton University Press, 2024), the late-nineteenth-century US Empire’s combination of economic nationalism, industrialization, and continental conquest made the American System the preferred model for Britain’s imperial rivals.[2] One unintended consequence of this protectionist transformation of the imperial order was also that the American System helped inspire anticolonial nationalists within the remit of the British Empire where free trade had been forced upon them, most notably Ireland, India, and China.

Continue reading “The Anti-Imperialism of Economic Nationalism: Transimperial Protectionist Networks in Anticolonial Ireland, India, and China”NIOD Rewind: The End of Empires and a World Remade

Martin Thomas and Anne van Mourik

NIOD Rewind

Did European colonialism truly end in the 20th century, as we often assume? In this episode Anne van Mourik (NIOD) speaks with Martin Thomas (Exeter University) about his book The End of Empires and a World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization (Princeton University Press). He argues that decolonization was not just the transfer of power from colonizers to the colonized, but a global, often violent process that forged new alliances, reshaped international connections, and left behind enduring colonial legacies. In this episode we ask: How to rethink decolonization? If empires were so powerful, military, politically, economically, why and how did they collapse? And how is colonial violence different than violence in non-imperial spaces?

Private Interest and Civil Governance in Colonial and Revolutionary Era America

Adam Nadeau

Among the more poignant observations made during the early days of overhaul of the United States federal government by President Donald Trump, his former senior advisor Elon Musk, and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) were a series of essays from Mike Brock’s Substack, Notes from the Circus. A former executive at Block Inc. who was involved in, among other things, building Cash App, Brock combines his insight into the world of big tech with his longstanding interest in philosophy to provide commentary on the current state of American democracy.[1] In one particularly illuminating post, Brock traces DOGE’s intellectual origins in part to a school of thought in Silicon Valley which holds that recent innovations in technology have rendered liberal democracy obsolete and that it is inevitable that Western democratic systems of government are to be superseded by digitally mediated, algorithmically optimized, corporatist technocratic autocracies.[2]

One might certainly agree with Brock that the pairing of corporate-technocratic power with the emergence of more advanced artificial intelligence threatens qualitatively unprecedented levels of social control and the attendant erasure of deliberative democratic processes.[3] However, it’s important to note that the blending of corporate entities and American political institutions is hardly a novelty of the twenty-first century. The fusion of private interest and civil governmental structures, particularly executive office, has been an integral part of the American political experiment dating back to the colonial and revolutionary periods, when private ventures backed by civil officeholders were the primary mechanisms for expanding colonial settlement, often with devastating effects on North American Indigenous populations.

Brock is correct to identify colonial opposition to the concentration of corporate power and state authority in the British East India Company (EIC) as one of the causal factors in the American Revolution.[4] However, his analysis misses the critical element that American revolutionary leaders were so strongly opposed to EIC activities in the thirteen colonies specifically because the Company represented a concentration of corporate power and state authority that was external to the colonies: the Tea Act of 1773 enforced a Company monopoly on tea in America that was meant to undersell tea on the colonial black market.[5]

Continue reading “Private Interest and Civil Governance in Colonial and Revolutionary Era America”Unfinished Revolutions: Decolonization and Democracy in a Globalizing World

Dr. Anubha Anushree

Editor at the Review of Democracy

Cross-posted from the Review of Democracy

Dr. Anubha Anushree reviews Martin Thomas’s The End of Empires and the World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization, Princeton University Press, NJ, March 2024, 608 pages.

The title of Martin Thomas’s The End of Empires and a World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization signals the ambitious and unconventional nature of his now widely acclaimed project. From the outset, Thomas frames decolonization not simply as a linear dismantling of empires, but as a complex and often contradictory process—one that simultaneously disintegrated old hierarchies and gave rise to new, and sometimes equally exclusionary, national orders. His emphasis on decolonization as a reintegrative force highlights how the collapse of imperial structures often yielded unstable, improvised formations of authority and belonging. The process was deeply entangled with the rise of nationalism and the promise of democracy—two forces that could be emancipatory but also repressive, generative yet limiting. Offering a global history of decolonization is no small task—it requires navigating this terrain of ambivalence, where the struggle for freedom often reproduced new forms of domination, and where the language of democracy could both expand and foreclose political possibilities.

What distinguishes Thomas’s book is precisely this encyclopaedic ambition to capture decolonization in its mutating forms across various parts of the world. Spanning a vast geographical terrain and the turbulent decades between the 1940s and 1990s, the book begins with a striking anecdote: the celebration of Kenyan independence in Nairobi on December 11, 1963. Seen through the eyes of Labour MP Barbara Castle, a vocal advocate for Kenyan independence in the British Parliament, the scene encapsulates the contradictions of decolonization. A regimental band plays Auld Lang Syne, evoking the solemn grace of British ceremonial tradition, even as Castle herself arrives late, scrambling over a fence and tearing her dress in the process. This chaotic juxtaposition—the orchestrated rituals of empire alongside the messy reality of postcolonial transition—mirrors the broader argument of the book: decolonization was not simply the rejection of colonial rule but an unpredictable leap into nation-building, improvisation, and disorder.

Thomas’s study interrogates these contradictions by expanding the definition of decolonization. It is not merely, as he writes, “the concession of national self-determination to sovereign peoples” (13), but also a generative force that “energized different ideas of belonging and transnational connections” (4).

Continue reading “Unfinished Revolutions: Decolonization and Democracy in a Globalizing World”Writing Histories of Settler Democracy in an Age of Crisis

Professor David Thackeray

Inaugural Lecture

Delivered on Wednesday 14th May, 16:00-17:00, Building One, Constantine Leventis Room

Recent years have been characterised by a range of debates about the legacies of the settler colonial past and how they should inform the state’s relationship with indigenous peoples. With the recent rejection of an ‘indigenous voice to parliament’ in Australia and ongoing efforts to redefine the state’s relationship with the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand it may seem that established postcolonial settlements are under threat. David’s inaugural lecture reflects on how recent public debates offer new opportunities to reconsider the contested history of settler democracy. The lecture focuses on three examples from the turn of the 20th century, which challenged understandings of ‘British’ democracy: the craze for debating societies among the unenfranchised, the growth of Maori parliaments, and the pioneer Indian MPs at Westminster.

[Starting at 15:56]

H-Diplo Roundtable on Pax Economica: Left-Wing Visions of a Free Trade World

H-Diplo | Robert Jervis International Security Studies Forum

Roundtable Review 16-39

Marc-William Palen, Pax Economica: Left-Wing Visions of a Free Trade World. Princeton University Press, 2024. ISBN: 9780691199320.

19 May 2025 | PDF: https://issforum.org/to/jrt16-39 | Website: rjissf.org | Twitter: @HDiplo

Editor: Diane Labrosse

Commissioning Editor: Diane Labrosse

Production Editor: Christopher Ball

Pre-Production Copy Editor: Bethany S. Keenan

Contents

Introduction by Jamie Martin, Harvard University. 2

Review by Martin Conway, University of Oxford. 6

Review by David Ekbladh, Tufts University. 9

Review by Sandrine Kott, University of Geneva and New York University. 13

Review by Francine McKenzie, Western University, Ontario. 16

Response by Marc-William Palen, University of Exeter 19

Introduction by Jamie Martin, Harvard University

Few conflicts have shaped modern mass political debate and mobilization more than the rivalry of free trade and neomercantilism. Yet the intellectual history of this conflict is underdeveloped. Marc-William Palen’s Pax Economica offers a major addition to a small yet growing body of scholarship on the intellectual history of trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by resurrecting a forgotten tradition of mobilization for freer trade among left and left-liberal intellectuals and activists.[1] He paints a vivid tableau of debate among well-known figures in the history of trade, such as the British politicians and campaigners Richard Cobden and Norman Angell, and the less familiar, including the Japanese Christian pacifist Toyohiko Kagawa and radical US feminist Florence Kelley, to show how a simple yet powerful idea circulated around the world: that protectionism made the world less equal and more violent.

Like any political concept, “free trade” is riddled with tensions. What did it mean, say, for a free trading imperialist in the British Empire, who praised its pacifying effects while defending its enforcement at gunpoint in places like India and China? And how could anticolonial visions of trade, which gained steam after the First World War, be squared with the ambitions of postcolonial states to jumpstart their development with protections? By focusing on debates like these, Palen unsettles common associations of free trade with the right or the neoliberal center, showing how, for example, it was an important socialist cause before the dawn of the Cold War. He even suggests the existence of a long-lost “Marx-Manchester” synthesis (93), which was once so tight that to be labeled a free trader, such as during the first US Red Scare in 1919–20, could be tantamount to being called a Bolshevik.

Palen’s book is full of bold arguments and unexpected details, from the tracts of anarchist free traders in Meiji Japan to Georgist designs for the boardgame that eventually became Monopoly.[2]It leaves the reader with the distinct feeling that the twenty-first century is weighed heavily by unresolved political questions from the nineteenth about the relationship of globalization and war, the effects of freer trade on domestic equality and distributional conflict, and the uses of tariffs for both developmentalist and reactionary political projects. The resurgence of old neomercantilist ideas in the 2020s, particularly on the right, Palen concludes, has left an opening for the return of equally old left visions of a “free trade world.” And so the conflict continues.

All four reviewers in this roundtable agree that Palen’s book is empirically rich and deeply researched, perspectival-shifting, and timely. David Ekbladh emphasizes the complexity and sophistication of the worldviews of the protagonists Palen uncovers, including pacifists who espoused deep understandings of the relationship of military power and economics. He also praises Palen for casting a staple figure of US mid-twentieth-century history, the Tennessee politician and Secretary of State Cordell Hull, in new light, which shows how Hull unexpectedly acquired a mass following, ultimately winning the Nobel Peace Prize. Palen argues that far from being a “contrivance to mask hegemony,” as Ekbladh puts it, US free traderism at the end of the Second World War had a deep well of support among a broad coalition of political activists and social movements.

Francine McKenzie similarly praises the diversity of voices in Palen’s work, its global reach, and the complexity of its depiction of the “sticky concept” of free trade. She also poses a series of queries for the book’s protagonists: how did they actually think lowering tariffs would, in practice, translate into emancipatory politics; and what made them optimistic about the prospects for a cause that had a relatively poor track record? She also emphasizes, as Palen agrees, that rediscovering the anti-imperialism of some free traders does not make free trade imperialism any less valid an analytic concept. McKenzie suggests a valuable point of departure for further research which involves an equivalently broad intellectual history of protectionism, which was not only a foil for free traders, but itself a cause that inspired many different movements and political actors. Here, the recent work of Eric Helleiner is key.[3]

Sandrine Kott similarly emphasizes the important contributions Pax Economica makes to the study of internationalisms and peace movements. She adds further complexity to the story by showing how the Soviet bloc’s Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) adopted free trade ideas during the Cold War. A similar point has recently been made by Oscar Sanchez-Sibony, who argues that Soviet leaders mobilized market ideas against the protectionist and market-distorting policies of their Western rivals.[4] Kott also suggests that a study which draws on other European contexts (as well as on Catholic thinkers as much as Protestants) could offer an important complement to Palen’s story, which is largely rooted in Anglo-American ideas and their global dissemination.

Martin Conway agrees that Palen’s work forces us to rethink assumptions about free trade ideas serving simply as a cloak for narrow economic or geopolitical interests, or as a “lost cause espoused by a fringe of naïve liberal groups.”At the same time, Conway also points to the challenges faced by globally-focused intellectual histories. He notes that as much as showing what united otherwise very different writers, it is equally important to consider the specific and context-bound nature of their political aims. The dissemination of free trade ideas, as Palen’s book shows, was itself driven by “Western globalization.” But these ideas took on lives of their own as they intersected with an array of political causes—from Indian independence to Chinese Nationalism to interwar US feminism.

These rich suggestions for future research and debate, and Palen’s response to his reviewers, all speak to the ambition and vision of Pax Economica—and to the importance of the story it tells for the politics of our own time.

Contributors:

Marc-William Palen is a historian at the University of Exeter. He is editor of The Imperial & Global Forum and co-director of History & Policy’s Global Economics and History Forum in London. His newest book, Pax Economica: Left-Wing Visions of a Free Trade World (Princeton University Press, 2024) was named one of Financial Times’ “best books of 2024” and made the New Yorker’s 2024 “best books” list. He is also author of The “Conspiracy” of Free Trade: The Anglo-American Struggle over Empire and Economic Globalisation, 1846–1896 (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Jamie Martin is Assistant Professor of History and of Social Studies at Harvard University. He is a historian of international political economy, empire, and the world wars. His book, The Meddlers: Sovereignty, Empire, and the Birth of Global Economic Governance (Harvard, 2022), received the 2023 World History Association Connected Book Award and the 2023 Transatlantic Studies and Cambridge University Press Book Prize and was shortlisted for the 2023 Susan Strange Best Book Prize. He is now writing a history of the world economy during the First World War. His public writing has appeared in The New York Times, London Review of Books, The Guardian, The Nation, n+1, and Bookforum.

Martin Conway is Professor of Contemporary European History at the University of Oxford. He is the author of a number of works on different aspects of the history of twentieth-century Europe, including Western Europe’s Democratic Age, 1945–1968 (Princeton University Press, 2020), which has also appeared in an Italian translation: L’età della democrazia (Carocci, 2023).

David Ekbladh is Professor of History and core faculty in International Relations at Tufts University. His books include, Beyond 1917: The United States and the Global Legacies of the Great War (with Thomas Zeiler and Benjamin Montoya, Oxford University Press, 2017), The Great American Mission: Modernization and the Construction of an American World Order (Princeton University Press, 2010), which won the Stuart L. Bernath Prize of the Society of Historians of American Foreign Relations, and Plowshares into Swords: Weaponized Knowledge, Liberal Order, and the League of Nations (University of Chicago Press, 2022).

Sandrine Kott is a full Professor of Modern European History at the University of Geneva and Visiting Professor at New York University. She has studied History in Paris, the University of Bielefeld, (FRG), and Columbia University (New York). Her main fields of expertise are the history of social welfare and labor in France and Germany since the end of the nineteenth century and labor (and power) relations in those countries of real socialism, in particular in the German Democratic Republic. In Geneva she has developed the transnational and global dimensions of each of her fields of expertise by taking advantage of the archives and resources of international organizations and particularly of the International Labor Organization. She has initiated in 2009 the History of International Organizations Network, a collaborative online research platform and seminar series http://www.hion.ch/.

Francine McKenzie is a Professor of History at Western University in Ontario, Canada. She is the author of Rebuilding the Postwar Order: Peace, Security and the UN-System, 1941–1948 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023), GATT and Global Order in the Postwar Era (Cambridge University Press, 2020) and co-editor of Dominion of Race: Rethinking Canada’s International History (University of British Columbia Press, 2017). She is in the early stages of two projects, one on the discourse of peace in the 1940s and another on tensions between the conception and practice of international trade and liberal theories.

Continue reading “H-Diplo Roundtable on Pax Economica: Left-Wing Visions of a Free Trade World”The End of Empires and a World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization – Interviews and Reviews

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

University of Exeter Professor Martin Thomas’s masterful book The End of Empires and a World Remade (Princeton University Press, 2024) continues to spark discussion, most recently for the New Books Network and H-Diplo.

New Books Network Interview

Martin recently sat down with Morteza Hajizadeh for the New Books Network for a wide-ranging exploration of the book’s key arguments, takeaways, and contemporary resonances. You can listen to the interview here.

H-Diplo Review

The End of Empires was also recently given an insightful review by Eva-Maria Muschik for H-Diplo, which is reposted below:

H-Diplo Review Essay 621

Martin Thomas. The End of Empires and a World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization. Princeton University Press, 2024. ISBN: 9780691190921.

20 March 2025

Review by Eva-Maria Muschik, University of Vienna

Martin Thomas’s The End of Empires is a rich book. Drawing on a wide range of English-language scholarship and a broad base of European archival materials, Thomas puts the issue of violence front and center and reminds us that twentieth-century decolonization was a globally connected process, but not strictly speaking a post-1945 phenomenon. In his understanding, it is also not a finished process. The emphasis throughout the book is on politics, especially individual conflicts, but also transnational networking and international law, economic matters, and the sociology of violence. Readers interested in learning more about the people, ideas, and culture that animated the global history of decolonization may need to turn elsewhere.

Continue reading “The End of Empires and a World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization – Interviews and Reviews”This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

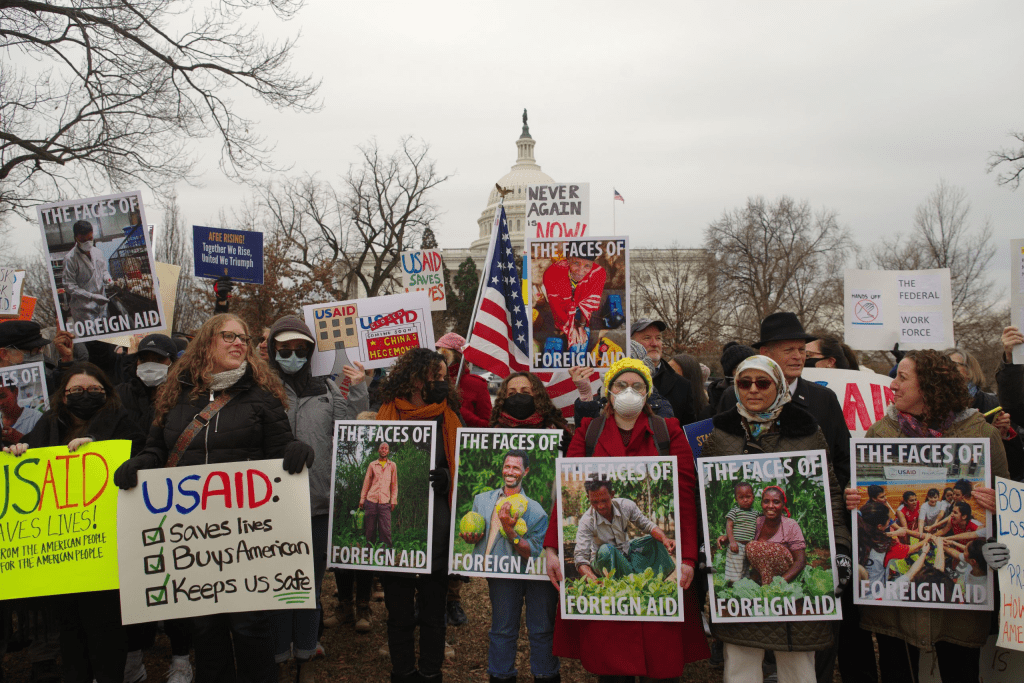

From life in Cuba under sanctions to liberal internationalism after USAID, here are this week’s top picks in imperial and global history.

Continue reading “This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History”This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History

Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

You must be logged in to post a comment.