Keisha N. Blain*

University of Iowa

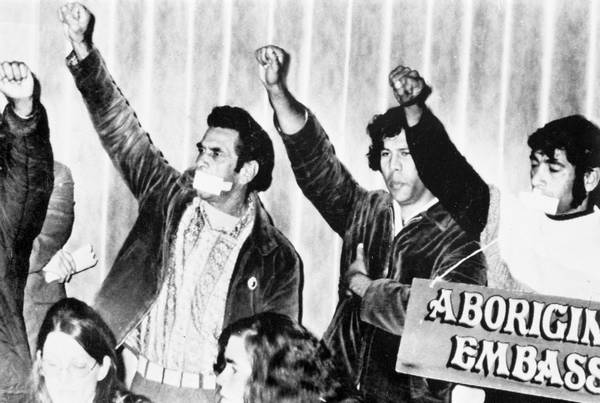

Historically, black men and women in the United States frequently linked national and geopolitical concerns. Recognizing that the condition of black people in the United States was “but a local phase of a world problem,” black activists articulated global visions of freedom and employed a range of strategies intent on shaping foreign policies and influencing world events.

During the early twentieth century, John Q. Adams, an African American journalist, called on people of African descent to link their experiences and concerns with those of people of color in other parts of the globe. Born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1848, Adams moved to St. Paul, Minnesota in 1886, where he became associate editor, and subsequent owner, of the Appeal newspaper. The paper’s debut coincided with key historical developments of the period including the hardening of U.S. Jim Crow segregation laws, the rising tide of anti-immigration sentiment, and the rapid growth of American imperial expansion overseas.

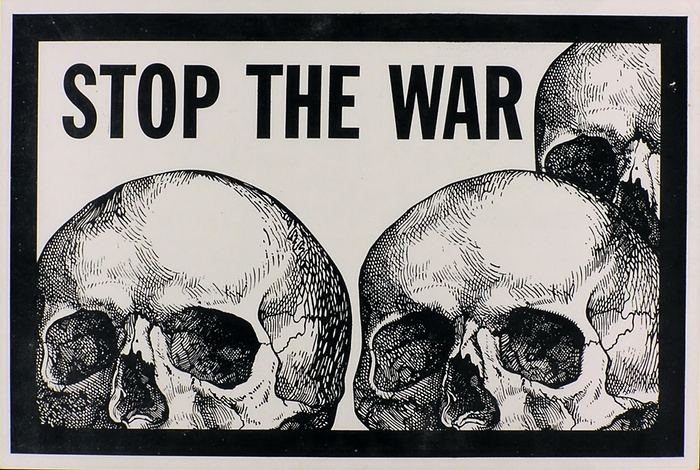

Amidst the sociopolitical upheavals of the early twentieth century, Adams utilized the Appeal as a public platform from which to denounce global white supremacy and advocate for the liberation of people of color. These ideas gained increasing currency during World War I, a watershed moment in the history of black internationalist politics. The millions of black people who served the War effort—in the United States and in colonial territories in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean—demanded the immediate end of discrimination, racism, colonialism, and imperialism. Continue reading ““End the Autocracy of Color”: African Americans and Global Visions of Freedom”

![mastersofempire_021915_B Cover[1][1]](https://imperialglobalexeter.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/mastersofempire_021915_b-cover11.jpg?w=250&h=313)

You must be logged in to post a comment.