Mathilde von Bülow

Lecturer in International and Imperial history, University of Nottingham

Today, Germany’s Mannschaft will face Algeria’s Fennecs at Porto Alegre, after both teams made it through the group stage of the FIFA World Cup. Though it has yet to be played, the match is already being hailed as an historic, even epic, event. Why? Because it represents the first time the Algerian squad has progressed to the final sixteen at a World Cup. Its larger symbolism, however, is rooted in a longstanding Algerian resistance to French colonialism, which underpinned the secret history of Algerian-German football relations.

The ‘Shame of Gijón’

Jubilant celebrations and pandemonium broke out throughout Algeria and beyond after Thursday’s 1-1 draw against Russia. A great moment of national pride and joy, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika reminded everyone that the Fennecs’ progression to the last sixteen carried with it the “hopes of the Arab nation and of Muslim and African peoples” everywhere.

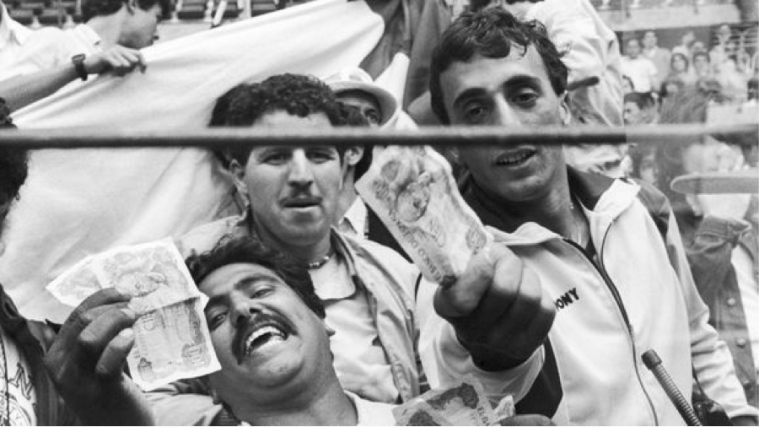

Significant and symbolic as it is in a tournament dominated by European or Latin American teams (although the ethnic makeup of those, especially the European, teams has itself changed dramatically, but that’s another story), Monday’s match is also being hailed as epic because, after thirty-two years, Algeria finally gets its chance to exact revenge for what has gone down in history as the ‘shame of Gijón’. One of the most disgraceful cases of alleged match fixing ever to have mired a FIFA World Cup, West Germany (as it was then) and Austria played a scoreline (1-0) in the final match of the 1982 group stage in Spain that ensured their mutual progression at Algeria’s expense.

What made this match all the more ignominious was the fact that Algeria had stood every chance to make it through to the last sixteen, having even secured a stunning 2-1 victory over West Germany in the group’s opening match. For the Germans, hotly tipped as one of the favourites to win the tournament (they made it into the final but lost the title to Italy), that game constituted one of the biggest surprises and upsets the team had ever faced at such an early stage in a World Cup. This was, after all, the first time the Algerian squadhad ever qualified for the tournament. So convinced were the German players of their superiority that they ridiculed their opponents in the pre-match conferences in a manner that would scarcely be tolerated today.[1]

Algerian Football as Anti-Colonial Resistance

Meanwhile in Algeria, the national team’s unexpected victory over such a formidable opponent had rallied the nation. Hopes and expectations ran high, all the more so since Algerians were celebrating the twentieth anniversary of their hard-fought independence from France. The players were filled with a sense of national duty, conscious that they represented the heirs to Algeria’s first national football team.

Founded in exile in April 1958 by the National Liberation Front (FLN), the movement that spearheaded the independence struggle, Algeria’s football squad had been a powerful symbol of Algerian resistance to French colonialism. Capitalising on football’s mass appeal, the squad served as an effective propaganda tool through which to rally Algerians to the FLN’s cause, forge a distinct national identity, and impress upon world opinion the patriotism, skill, discipline, and tenacity of the Algerian people in their struggle for freedom. Several of the FLN’s original players went on to form the new national team after that freedom was won; several continued to serve on the 1982 squad’s coaching and managerial staff.[2]

Contrary to common belief, however, 1982, was not the first footballing encounter between Algeria and West Germany.The two sides had met once before, on New Year’s Day 1964, after the Mannschaft became the first Western team to be invited to Algeria for a friendly match. Then, too, the Algerians came out on top – this time with a 2-0 win. And then, too, the West German squad had been considered by everyone to be the vastly stronger side (the team went on to contest the 1966 World Cup against England).

Considering that the FLN’s original football team never actually played a match in, or against, West Germany during the independence struggle, the fact that Algeria’s Football Federation invited the Mannschaft as one of the first teams to play its newly formed squad seems rather odd, as does the West German Football Federation’s decision to accept. After all, the Algerian Federation had yet to join FIFA, which, in response to French pressure, had threatened harsh penalties against those who engaged with the FLN’s team.

What’s more, Federal Germany had been one of France’s staunchest allies all throughout the Algerians’ independence struggle. The Bonn government had refused to have anything to do with the FLN until, that is, the latter had led Algeria to independence.[3] At that point Cold-War rivalries kicked in and Bonn came grovelling, fearful the Ben Bella government, with all the prestige it enjoyed throughout the ‘Third World’, might recognise the East instead of the West German state. It took the persuasive power of ‘chequebook diplomacy’ for Bonn to stave off this nightmare scenario, which for a while at least seemed like a real possibility considering East Germany’s generous aid to the FLN throughout its fight for national liberation.[4]

The Secret History of Algerian-German Relations

And yet, this official narrative obscures a complex, often secret, history of connections between the two countries that run far deeper than is generally known. The Bonn government might have shunned the FLN and all its representatives during Algeria’s war of independence, but this didn’t stop the latter from setting up safe houses, workshops, bank accounts, and training camps in West Germany that all served to sustain the fight against France.

In 1958, the country became a base from which the FLN launched and coordinated the war’s ‘second front’ in metropolitan France; it served as a hub for the clandestine transfer of militants, army deserters, and funds from the metropole to North Africa; and it became one of the preferred locations whence the FLN secretly procured arms, munitions, radio communications equipment and other vital supplies. These activities created constant and severe tensions between the governments in Bonn and Paris since the latter accused the Germans of harbouring terrorists.

The FLN, meanwhile, had become so effective at subversion that the German security services never quite managed to catch up with them. On more than one occasion this prompted the French secret services to intervene directly, often with unintended and deadly consequences.

Meanwhile, West Germany also became a vital sanctuary for thousands of Algerian refugees fleeing from police repression, political violence, and internecine warfare in metropolitan France (mirroring circumstances in North Africa, just on a smaller scale). These refugees, almost all of whom were young, unskilled or semi-skilled, male workers who had left their families in Algeria in order make a living in France’s industrial centres, who were destitute and lacked all knowledge of German, posed an equally serious social, political, and diplomatic problem for Bonn.

The FLN’s supporters pressured the government unrelentingly to extend political asylum to these Algerians. French authorities, meanwhile, insisted on the refugees’ immediate transfer into their custody, arguing that they were likely to be ‘rebels’, ‘criminals’ and ‘terrorists’. Faced with these conflicting pressures and constrained by legal restrictions, the Bonn government had no choice but to tolerate the Algerians’ presence so long as they refrained from political or subversive activities, though it denied them the legal status of refugees.

As such the Algerians’ existence in West Germany remained precarious. If securing work, shelter, and subsistence proved a daily challenge, it was rendered all the more difficult by mutual incomprehension and colonial stereotypes that imbued German reactions to the new, darker-skinned arrivals in their midst. After all, the basic racial convictions that had underpinned German colonialism before the Great War, and that then went on to inform Nazi ideology after it as Jürgen Zimmerer argues (not uncontroversially), did not necessarily dissipate overnight.[5]

Most refugees depended on the charity and assistance of local aid organisations, trade union branches, student associations and leftist political movements to secure even the basics needed to subsist. In many cities across West Germany, local aid committees emerged to help new arrivals. In conjunction with the aforementioned organisations, these committees arranged shelter for the Algerians, mediated on their behalf with the authorities, provided legal council, organised jobs and apprenticeships, raised funds for scholarships and language tuition. Even those who benefited from this help found life in Germany tough, however, as evidenced by the reports produced both by the aid committees and by Algerian trade union representatives.

One letter, dated April 1961 and written in broken German by a group of twenty-four Algerians to Willi Richter, head of the West German Federation of Trade Unions (DGB), is particularly moving. In it, the Algerians, who had been selected to participate in an eighteen-month trade union training programme, expressed their heartfelt thanks for the DGB’s generosity in funding their education. Grateful as they were for the opportunity to improve their skills, knowledge, and material prospects – all of which they planned to apply to forging a new Algerian nation – one donation had given them particular joy: the gift of twenty-four football kits, including cleats.

Faced with the material and psychological pressures of exile amidst a brutal and dirty conflict that had claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and displaced millions both internally and externally, the chance to play football represented a welcome and needed release, a brief moment in which to forget the horrors or war and enjoy life. Football also provided these Algerians with an opportunity to bond and communicate with their German hosts on an equal playing field. As the Algerians proudly informed Richter, the kits and cleats “already helped us to one victory in a football match when we played against a team composed of young German colleagues from the [trade union] school.”[6] Just like the FLN’s national team, therefore, these young men used the sport to impress upon their opponents that Algerians, too, were people of worth whose only obstacle to realising their full potential was the condition of colonial oppression that they were forced to endure.

Football Diplomacy

Football, then, played an important role in facilitating and generating German-Algerian mutual understanding and respect at a time when official relations between the two countries did not even exist. Racial stereotypes and daily hardships aside, the growing interaction such matches fostered amongst Algerians and locals helped turn the tide of West German public opinion decisively against ‘French Algeria’ and for the FLN.

The German national team may have never played a game against the FLN’s squad, but this did not prevent Eintracht Frankfurt – the club that had won the 1959 West German football championship – to invite several members of the Algerian squad, who were passing through Frankfurt over Christmas that same year after an extended visit to the People’s Republic of China, as guests of honour to one of its matches.[7] Eintracht Frankfurt extended this gesture to the Algerian players in spite of the fact that they were returning from the hated Communist bloc and in opposition to FIFA’s ruling. Simple as it was, the gesture constituted a symbolic act of respect for, and solidarity with, the Algerian team.

This respect, it seems, was lost on the German national squad when it finally did meet the Algerians on the pitch both in 1964 and in 1982.

One can only hope that it has learnt its lessons from the humiliations of the past. Superior as they may be as a side, the German players should not rely on old racial and cultural stereotypes to lull them into a false sense of security. Rather, they must face the Algerians as equal, worthy challengers. This, in the end, is what sport is all about. Whatever the outcome of Monday’s match, les Fennecs have already made history.

Dr. von Bülow is a Lecturer in International and Imperial history, University of Nottingham. She is completing a monograph for Cambridge University Press that examines West Germany’s role as a rebel sanctuary during the Algerian war of independence.

—-

[1] It was the ‘shame of Gijón’ that prompted a change of FIFA regulations whereby the final matches at group stage would be played simultaneously rather than consecutively in order to prevent rigging. For a good overview, see Paul Doyle’s article: http://www.theguardian.com/football/2010/jun/13/1982-world-cup-algeria.

[2] Michel Naït-Challal et Rachid Mekloufi, Dribbleurs de l’indépendance: l’incroyable histoire de l’équipe de football du FLN algérien (Paris: Editions Prolongations, 2008); Kader Abderrahim, L’indépendance comme seul but (Paris-Méditerranée, 2008).

[3]Jean-Paul Cahn and Klaus-Jürgen Müller, La République federal d’Allemagne et la guerre d’Algérie, 1954-1962 (Paris: Le Félin, 2003); Nassima Bougherara, Les rapports franco-allemands à l’épreuve de la question algérien (1955-1963) (Bern: Peter Lang, 2006).

[4]On East German relations to the FLN, see Fritz Taubert, La guerre d’Algérie et la République Démocratique Allemande (Editions universitaires de Dijon, 2010).

[5]Jürgen Zimmerer, “Annihilation in Africa: the ‘Race War’ in German Southwest Africa (1904-1908) and its Significance for a Global History of Genocide,” GHI Bulletin 37 (Fall 2005), pp.51-7; idem, Von Windhuk nach Auschwitz? Beiträge zum Verhältnis von Kolonialismus und Holocaust (Münster: LIT Verlag, 2011).

[6]Archiv der sozialen Demokratie, Bonn, Nachlass des DGB, Akte 5/DGAJ/000207, Brief von Saïd Rabah et al an Willi Richter, 28 April 1961.

[7]Naït-Challal et Mekloufi, Dribbleurs de l’indépendance, pp.150-1, 162-3.

I see a lot of interesting posts on your blog. You have to spend a lot of time

writing, i know how to save you a lot of work, there is a tool that creates unique, SEO friendly articles in couple of

minutes, just search in google – laranita’s free content source

Hello my loved one! I want to say that this article is awesome, great written and

include almost all important infos. I would like to

see more posts like this .

I read a lot of interesting posts here. Probably you spend a

lot of time writing, i know how to save you a lot of

time, there is an online tool that creates unique,

google friendly articles in seconds, just type

in google – laranitas free content source

Because the admin of this website is working, no question very shortly it

will be well-known, due to its feature contents.

Interesting article. It shows the power of football as a social/political tool (which also underlines the power of FIFA and why such an organisation should be free of any suggestion of corruption). As for the West Germany-Austria game, I recall watching that and feeling disgusted. However it wasn’t the first, nor the last, World Cup tie to be fixed.

It is thé first time to Know the aide of the west germany People and gouvernement and aide of different associations to thé algerian refuges from France and teaching thème. Many thanks for two republics.

I TRY to matériel research on this subject

Ali. Algiers

Hi!

I discovered the movie.

Zidane play at Bordeaux. His pass is cool!

King regards