Daniel Foliard

Assistant Professor, Paris Ouest-Nanterre la Défense University

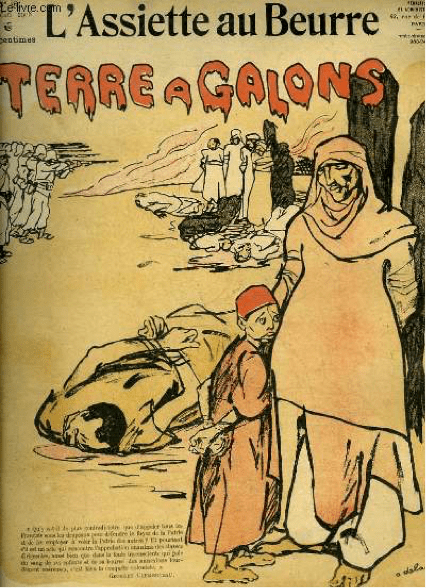

In a recent interview, George Wolinski (1934-2015), one of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists killed in the Paris terrorist attacks on January 7, 2015, had claimed his magazine’s work was the legacy of L’Assiette au Beurre, an innovative satirical weekly published in France between 1901 and 1912.[1]

Both stylistically and politically, the two periodicals, separated by more than a century, could also claim an affiliation with a long French tradition of dissent. Accordingly, although Charlie Hebdo is now known around the globe for its unmediated satire on religions, we should not overlook its position in the longer history of French anti-imperialism.

The 1881 laws on the freedom of the press had opened the golden age of French political caricature, paving the way for Samuel-Sigismond Schwarz to found L’Assiette au Beurre in 1901. The new illustrated weekly was, however, initially a failed commercial venture.

André de Joncières took over in 1904 when Schwarz went bankrupt. The new owner continued its founding tradition, running the paper with little or no censorship. Some of the most prominent artists of the early 20th century — Willette, Juan Gris, Félix Vallotton, Caran d’Ache among many others — rushed to publish their drawings in a paper that offered them an unprecedented freedom of speech as well as an incredible stylistic liberty.[2] Other satirists such as Jules Grandjouan and Henri Gustave Jossot contributed to give it an anarchist stance. But the paper had no definite editorial line except an all-out attack on established interests.

L’Assiette au Beurre targeted the establishment indiscriminately. The paper was fiercely anticlerical and antimilitarist. It also launched virulent attacks on European colonialism in all its forms. Thematic issues regularly addressed foreign affairs and imperial expansion.[3] Graphic cartoons denounced colonial atrocities such as Papka’s horrific execution in Fort Crampel (Oubangui-Chari, Central Africa) on July 14, 1903, wherein two French government administrators, Gaud and Toqué, decided to kill the suspect with dynamite to strike the locals with awe. Nor was French colonial violence L’Assiette au Beurre‘s only target. In 1901, for instance, Jean Veber directed an issue devoted to the concentration camps in the South African Transvaal.[4]

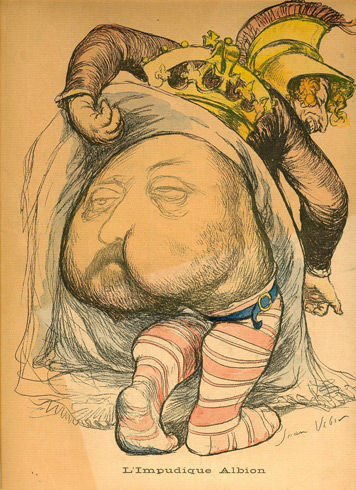

The paper was not spared from government censorship. The authorities considered Jean Veber’s 1901 cartoon showing an indecent Britannia (“impudique Albion”) exposing an Edward VII-shaped bottom to be too scandalous — at least after the British government summoned the French Ambassador in London.

A tiny skirt was added to cover the offensive body part.[5] Special issues on religions depicting a sword-wielding Mohammed or a crucified Christ overlooking priests torturing bodies did not raise such an outcry as Britannia’s overexposed fundament.[6]

L’Assiette au Beurre nonetheless enjoyed much more freedom than some of its late-19th-century predecessors. And even though the satirical magazine of opinion was unable to survive the growing intolerance of the last years of the Belle Époque, the artistic, satirical and anti-imperial prowess of the publication made it a lasting reference for generations of caricaturists in France.[7]

From this longer perspective, Charlie Hebdo’s murdered cartoonists were among the last standing custodians of L’Assiette au Beurre’s irreverent and pioneering denunciation of French colonial oppression. George Wolinski and Jean Cabut (also known as Cabu) belonged to a generation haunted by the horrors of the war in Algeria (1954-1962) and the ruthless counterinsurgency applied by the French Army. Cabut himself was sent with his regiment to Constantine in the late 1950s. This greatly contributed to his political awakening.

Cabut and Wolinski had embraced their artistic career at Charlie Hebdo in a context of colonial violence that they despised, with a view to carry on a long tradition of French secular and political satire. Hopefully it’s just a matter of time before someone else will take up the torch.

————–

[1] Wolinski: “Le désir, c’est encore mieux que le plaisir !”, L’Humanité, January 28, 2011.

[2] See Élisabeth Dixmier and Michel Dixmier, L’assiette Au Beurre : Revue Satirique Illustrée, 1901-1912 (Paris: F. Maspero, 1974). Or S. Applebaum, French Satirical Drawings from “L’assiette Au Beurre”: Selection, Translations, and Text (Dover Publications, 1978).

[3] Colonisons, February 26, 1902; L’Algérie aux Algériens, May 9, 1903; Les Bourreaux des Noirs, Mars 1905 ; Le Maroc, December 5, 1903 ; Civilisons le Maroc, August 31, 1907.

[4] Les Camps de Reconcentration au Transvaal, September 28, 1901.

[5] Jean Veber, “Impudique Albion”, September 28, 1901.

[6] Religions, May 17, 1906.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.

Pity they strayed from that path over time – http://tinyurl.com/nxc7d87 As you wrote, hopefully “someone else will take up the torch”.

Reblogged this on Blinded by the Darkness.