Tobias Rupprecht

University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @Tobepastpresent

Russia has re-emerged as an imperial power during Vladimir Putin’s third term as president. In the Syrian civil war, the Russian military intervention turned the tides in favour of Bashar al-Assad. The Kremlin has incited separatism and war in Ukraine, supports Serbian nationalists and secessional Abkhazians, has refreshed traditional friendships with Bulgaria and Macedonia, and it has struck a deal with the Cypriote government that allows the Russian navy to use the island’s ports. In the Southern European debt crisis, Russia offered substantial financial aid to Greece. What links all these countries is that they all are traditionally home to large groups of Orthodox believers. Is this a coincidence?

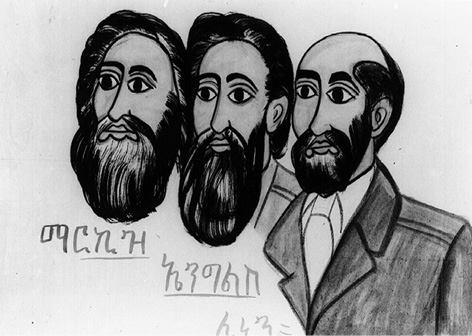

In a recent article in Comparative Studies in Society and History, I argue that religious traditions and religion-based visions of world order often impinge on the making of foreign policy and on the nature of International Relations. I make that case using the history of the mutual cross-relationship of church and state in modern Russia and Ethiopia. From the late nineteenth century, both multi-ethnic empires with traditionally orthodox Christian ruling elites, developed a special relationship that outlived changing geopolitical and ideological constellations. Russians were fascinated with what they saw as exotic brothers in the faith; Ethiopians took advantage of Russian assistance and were inspired by various features of modern Russian statecraft. Religio-ethnic identities and institutionalised religion have grounded tenacious visions of global political order and cross-border identities. Orthodoxy was the spiritual basis of an early anti-Western type of globalisation, and was subsequently co-opted by states with radically secular ideologies as an effective means of mass mobilization and control.

In both Russia and Ethiopia, the modern state has been intrinsically intertwined with Orthodoxy. On the one hand, the Orthodox churches were subjugated to the demands of their respective states, regardless of changing governments and their ideological orientations. Yet, while Orthodoxy was co-opted by the state, it did not lose its efficacy altogether. The churches often pursued their own interests in the international arena. And ideologically, anti-Western and anti-materialist traditions of Orthodoxy impinged on political decision-making in St. Petersburg/Moscow as much as in Addis Abeba, creating a sense of belonging among elites of both countries – quite apart from the relative lack of any actual theological accord on what Orthodoxy means. The political obligations cemented and enacted by the mutual recognition of being Orthodox kin endured in substantial ways even after their respective shifts to communism, in spite of official hostility toward religion as such.

In Soviet times, the normative ideology changed with communism but the special relationship with Ethiopia continued. As did the Tsars before them, the Soviets gave military aid to Ethiopia and sent it technical advisors. The education of Ethiopian students in Russia began at the turn of the century and reached its apex in the Soviet Union’ s last decade. Russian and Ethiopian theologians maintained direct contacts throughout the communist period. Like the bond between church and state in each country, that between the two countries outlived successive geopolitical and ideological constellations, displaying the longevity of visions of global order based on church affinities.

Religion, however, matters not only in its institutional form in foreign relations and domestic politics. As I propose in ‘Orthodox Internationalism’, political cultures and mental maps also have some of their roots in religious traditions. Orthodox believers were used to declarations in a language that they were expected to follow, not to understand, and they were accustomed to accepting the authority of a priestly caste as representatives of the nation. The revolutionary vanguard that took over the role of the clergy, in Russia in the 1920s and Ethiopia in the 1970s, had to change the content but not the form of their annunciations. In both places, the communists wreaked havoc with many traditions, but they also successfully claimed legitimacy by referring to the deep-rooted anti-Western and anti-liberal resentments of Orthodoxy.

Russia’s geopolitical mission today follows Orthodox geography, and is supported by the Russian Orthodox Church. Anti-Western and anti-liberal sentiments, with their own ideational roots in Orthodoxy, are prevalent as ever. Russian views of world order, to be sure, are more a conglomerate of religion-inspired cross-border identities than expressions of genuine spirituality. Below the surface of a revived religious nationalism and Orthodox solidarity, church attendance in Russia remains very low. And many more factors beyond religion contribute to the making of Russian foreign policy. But the Kremlin’s predilection for countries with Orthodox populations is more than a coincidence and suggests that religion-inspired visions of world order remain relevant in twenty-first-century international relations.

It’s an interesting similarity that I had no awareness of, but I wonder where the self-interest for the Russian state lies, since it has had an almost marginal role in the grab for Africa