Tom Harper

On the 22nd November 2003, an electrical power worker from the Chinese province of Henan, Wang Letian, walked around his home city of Zhengzhou wearing a traditional Chinese costume called the Hanfu. Wang intended to promote traditional Chinese culture by generating interest in traditional Chinese garb. At the time, Wang’s actions were unusual, with the Hanfu being largely confined to film sets and tourist attractions.[1] Nevertheless, Wang received significant attention in China, and has often been cited as the originator of the current Hanfu craze sweeping China today.

Wang’s goal of promoting Chinese traditional culture appears to have been fulfilled in recent years, with the costume becoming a mainstay of social media platforms popular with Chinese millennials. The popularity of the costume coincides with a wider discussion over the state of China’s identity, which marks a break from the previous focus on China’s economic development.[2] This has often sought to emphasise the uniqueness of China’s identity as well as presenting China as a civilisation state rather than a nation-state in the Westphalian sense.[3] By delving into China’s past, the rise of the Hanfu movement and the debate over China’s identity thus symbolises the contradictory nature of the legacies of China’s imperial dynasties, most notably the Ming and Qing dynasties, as well as the role that these have played in shaping the present Chinese perception of China.

Pride and Shame

The term Hanfu (汉服) generally refers to the clothing of the Han race that makes up the majority of China’s population. This broadly incorporates all forms of Han clothing prior to the 17th century. As with many concepts from the early years of China’s history, the origins of the garb has partially been shrouded in myth and legend, with the claim that the Hanfu was the costume of the legendary Yellow Emperor, the sage king of ancient China. As a result, it has been difficult to trace the exact origins of the garb since it has been difficult to separate myth from reality. Nevertheless, it has been traced to the time of the Shang Dynasty of 1600 BC and 1000 BC. This initially took the form of a knee length silk tunic, known as a yi, secured with a sash and a narrow ankle length skirt called a chang, which was worn with a length of silk called a bixi that reached the knees. The style of the Hanfu was subject to change over time until the beginnings of the Qing Dynasty in 1644, when the costume fell out of fashion in favour of Manchu garb such as the cheongsam.

The emergence of the Hanfu movement has been representative of the latest shift in how China’s imperial legacies have been perceived. Previously, these were seen as a source of shame, most notably during the Mao era in the mid 20th century, with China’s traditional culture being blamed for China’s humiliation during the 19th and 20th centuries.[4] As a result of the apparent failings of what Wang Gungwu termed the Confucian ‘emperor state’, Chinese reformers from the ‘Self Strengthening Movement’ to the Communist Party of China sought to utilise Western ideologies and concepts to modernise China, most notably the concept of the nation state and the communist and nationalist doctrines.[5] The early years of the People’s Republic of China emphasised China’s ideological identity as a leading communist nation rather than China’s previous cultural state. In keeping with the earlier trends of China’s modernisers, Mao saw China’s traditional culture and the Confucian orthodoxy as the reason behind China’s backwardness. This became more pronounced in the later years of Mao’s rule; China’s traditional culture was even labelled as one of the ‘Four Olds’ that was seen as requiring destruction during the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976.

The perception of China’s imperial legacies and traditional culture shifted after Mao’s death in 1976 and the subsequent period of reform and opening-up initiated by Deng Xiaoping. This saw the abandonment of the ideological goals of the Mao era in favour of a focus on China’s economic development. As a result, China lost one of its main organising principles, which was further compounded by the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and Russia in 1989 and 1991 and the subsequent onset of Post-Cold War globalisation. All of these contributed to a wider identity crisis within China, with the promotion of Western popular culture through globalisation being perceived as eroding China’s identity.[6]

To remedy this, the Communist Party of China (CPC) turned towards Chinese nationalism as a unifying force. This initially manifested itself in the disputes with Japan over the legacies of the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937 to 1945, most notably in the adverse Chinese reaction to the recent visits of several prominent Japanese political figures, including former Prime Ministers Junichiro Koizumi and Shinzo Abe, to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine. The Tokyo shrine’s controversy was due to its commemoration of several Japanese Class-A war criminals from the period, including its wartime leader, Hideki Tojo. This also saw a Chinese revival of the Confucian doctrine that had been suppressed during the Cultural Revolution. All of these formed the roots of the later perceptions of China’s past and identity.

In recent years, China’s imperial legacies and past achievements have been utilised as a source of Chinese national pride. The CPC has used these legacies as part of a wider effort to build support for Chinese policies at home and abroad, by presenting modern China as the latest stage of ‘five thousand years of Chinese civilisation’. The use of these legacies marks a break from the previous utilisation of China’s past for political goals, with China’s golden ages replacing the use of the ‘Century of Humiliation’.[7] These changes have also been a result of a renewed interest in the state of China’s identity, which has been one of the core objectives of what has been termed as the ‘Third Revolution’ under Xi Jinping. One of the notable recurring features of this has been the perceived uniqueness of Chinese identity. This was articulated in Liu Mingfu’s 2015 bestseller The China Dream, which called for China to embrace a uniquely Chinese destiny as opposed to seeking convergence with the developed world.[8]

While China’s perceived golden ages of the Han, Tang, and Song dynasties have often been invoked by the CPC, there has also been a growing interest in the more contentious aspects of China’s imperial legacies. This has been most notable with the debates over the Ming and Qing dynasties.

The Hanfu movement being the most recent manifestation of the debate over the nature of China’s identity and past legacies.

Contentious Legacies: The Legacies of the Ming and Qing Dynasties

The emergence of the Hanfu movement, while primarily being utilised as a symbol of China’s renaissance, has also been expressive of China’s Han identity. This has been linked to the wider discussion over the legacy of the Ming Dynasty. As the last ethnically Han rulers of the Chinese Empire, the Ming has traditionally been seen as a dynasty that began its rule with great potential but ultimately fell short of its promise. This potential was symbolised by the Treasure Fleets of Zheng He in the 15th century, which has often been invoked as a motif for China’s relationships with the African states and to promote the image of China as an outward-looking nation that seeks to play a greater global role[9].

This initial promise was seemingly extinguished by the inward turn that China’s rulers took in the second half of the Ming Dynasty’s rule in the 16th and 17th centuries, symbolised by the dismantling of the Treasure Fleet after its’ return. As a result, this has often been interpreted as China foregoing any effort to create an overseas empire like the later European powers would do, and instead turned towards the increasingly difficult task of controlling China’s borders in the face of the challenges posed by the Mongols and the Manchus.[10] If the Treasure Fleet symbolised the outward-looking promise of the early Ming dynasty, the Great Wall can be seen as a symbol of the inward turn of the Ming dynasty’s later years.

In recent years, there has been an effort by amateur online historians to rehabilitate the tarnished legacy of the later years of the Ming dynasty. These have often sought to present Ming China as a progressive force that was the most powerful nation of its’ day.[11] Such an interpretation presents the Manchu invasion of China as an end of the progressive governance of the Ming, which condemned China to backwardness.

The Qing Dynasty has also become part of the more contentious aspects of China’s imperial legacies. The rule of the Qing Dynasty has often been seen as a period of alien rule, with China’s Manchu rulers distinguishing themselves from their Han subjects. One such distinction came in the form of a series of laws concerning clothing. This included regulations making the queue hairstyle compulsory, known as “cut the hair and keep the head or keep the hair and cut the head” (留髮不留頭,留頭不留髮) as well as requiring officials to wear Manchu garb. These rules have been presented in the recent discourses on this period as being a part of an effort by the Manchus to suppress Han culture including traditional clothing such as the Hanfu.[12] As a result, the popularity of the Hanfu has been presented as a rediscovery of Han imperial culture.

These rules would further reinforce the perception of the Qing emperors as a privileged foreign elite in the eyes of the Han majority, who had still not fully accepted their rule, particularly in China’s southern regions which were the last strongholds of the Ming loyalists. This perception would have adverse consequences for the Qing that culminated in the events during the dynasty’s twilight years in the 19th century.

As well as being seen as a period of alien rule, the Qing Dynasty has often been presented as an age characterised by China’s humiliation, marked by China’s defeat in the First Opium War of 1839. The later Qing period was an era beset by conflict and rebellion as well as several efforts to modernise the Qing Empire that ultimately failed. These experiences have also been seen as one of the primary motivations for China’s push to become a Great Power as well as being invoked in more contentious periods in China’s foreign relations.

The linkage between the popularity of the Hanfu and the contentious legacies of China’s imperial past were illustrated by a 2013 memorial to Ming loyalists at Wuxi. This was further underlined by similar pilgrimages made by the Hanweiyang and Jiangyin Hanfu associations.[13] In commemorating these events, the pilgrimages emphasised the role of Han identity, with the Ming loyalists being the last bastions of Han rule in imperial China. As a result, the present Hanfu craze as well as these legacies have been a wider expression of China’s Han identity, which has posed questions for the state of China’s present identity.

While the popularity of the Hanfu movement has been seen as a symbol of China’s past achievements, it has equally been the result of a discussion of the more contentious elements of China’s early modern period. These developments have been expressed by the Hanfu craze in several ways.

The Hanfu Craze and Chinese Nationalism

While the origins of the Hanfu movement are rooted in Wang Leitian’s use of the costume nearly twenty years ago, the proliferation of it has been a comparatively recent development. Before the rise of social media, the Hanfu revival was largely confined to small groups of enthusiasts, and it required a greater amount of individual effort to penetrate.[14] While the garb was initially popularised in the early 21st century through novels and period dramas, social media applications served as the driving force behind the present Hanfu craze, enabling enthusiasts to spread their passion for the costume on a far greater scale than before.

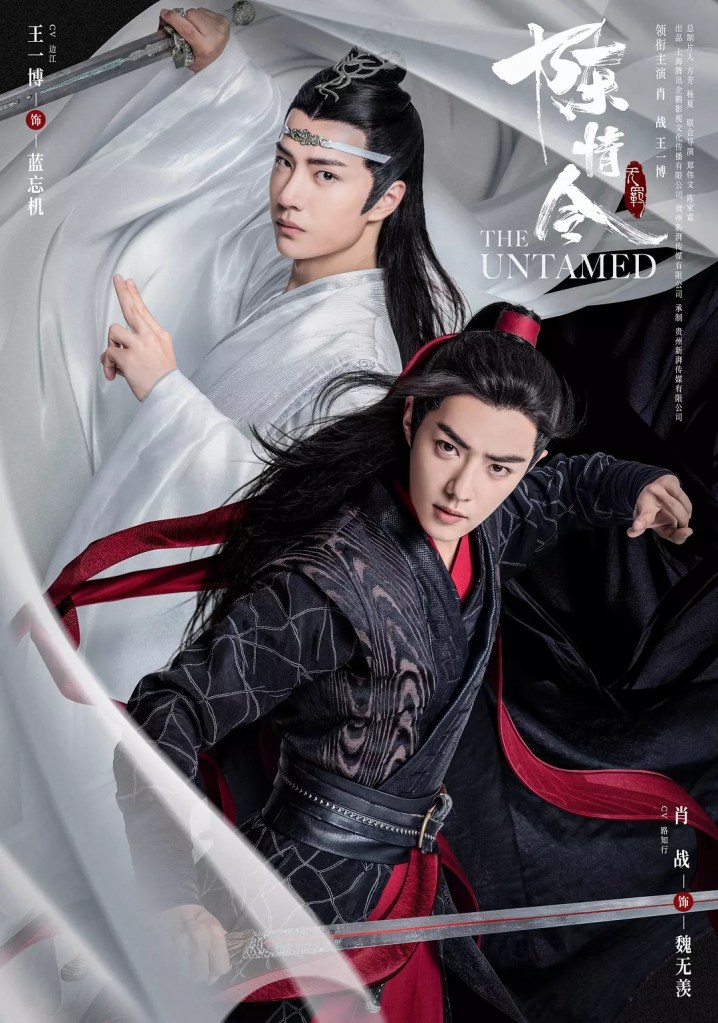

Possibly the most notable example of this was the 2019 TV series The Untamed, which was adapted from the Chinese fantasy (Xianxia) novel Mo Dao Zu Shi by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu. The series has been cited as a notable factor behind the popularity of the Hanfu, with viewers of the series seeking to acquire costumes and props worn by the cast.[15] The popularity of The Untamed shows one of the ways by which the Hanfu was popularised.

Through the lens of cultural transmission, it is possible to identify the trends that the Hanfu movement represents. One of these comes in the demographics of the movement, which primarily consists of Chinese millennials. This generation has been more confident than previous generations, having grown up in the period of China’s rapid development in the 1980s and 1990s.[16] As a result, they have often sought to express their own unique identity, with the Hanfu being one of the means to do so.

The demographics of the Hanfu movement also indicate a divide in attitudes between generations, as well as with the Chinese government. This was demonstrated by an attempt to make the Hanfu part of China’s official national costume in 2008. although it was rejected by the government.[17] Such an outcome echoes the common criticism of how the government is primarily focused on China’s economy rather than its identity[18].

Hanfu’s popularity is a testament to the economic clout and influence of China’s millennials.[19] The influence of this generation has led to comparisons between them and the baby boomer generation in the developed world, with Chinese millennials being perceived as the new baby boomers in terms of size and influence. As a result, the popularity of the Hanfu is an illustrative expression of the influence of this generation, which will be a notable feature of the near future, with Chinese millennials having the potential to shape trends even more than the baby boomers had before them.

The Hanfu craze has also been a feature of the wider backlash against globalisation. While the primary forms of this reaction have typically been anti-capitalist or nativist in character, in this case, it has been more cultural in nature. This has been a result of a countermovement against the spread of Western as well as non-Chinese forms of Asian popular culture, which had contributed to China’s Post-Cold War identity crisis.[20] In this sense, the popularity of the Hanfu is part of this wider nativist attempt to promote the traditional imperial culture of the Ming Dynasty.

This raises contentious contradictions within the today’s conceptualisations of Chinese identity. This has been notable in the backlash against other forms of Chinese clothing, such as the qipao, which has been seen as foreign ‘Manchu’ garb. Conversely, the Hanfu is now being presented as a uniquely Chinese form of clothing.[21] Han and Chinese are often now perceived as largely synonymous. This has been apparent on the same online platforms that did much to popularise the Hanfu.

Wangluo Mingshi Pai and the Rise of Online ‘Hanist’ Nationalist Discourse

The popularity of the Hanfu has partially been a result of a renewed interest in discussing the nature of China’s imperial past as well as its national identity. While these legacies have often been invoked by Chinese officials, as demonstrated by the earlier refrain of ‘five thousand years of civilisation’, these have also been subject to discussion by an emerging group of amateur online historians, who have created their own discourses on these legacies that differ from official narratives in several ways.

One such difference is in the nationalistic tone that they take. While the official Chinese stance has become more nationalistic in recent years, the online discourse has emphasised the Han aspect of Chinese identity, which has led to them being characterised as ‘Hanist’.[22] This strand of online ethnonationalism has also presented the Ming Dynasty as the last golden age of imperial China and has also seen the Qing Dynasty as a period of alien rule that snuffed out the progressive rule of the Ming.

While these activities have largely been confined to online forums such as the Hanwang, this strand of nationalism has also made its presence known offline. Alongside the commemoration of Ming loyalists battling the invading Manchus in the 16th and 17th centuries, this tendency manifested itself in the Huang Haiqing slapping incident in Beijing in 2008. Huang, an avid consumer of nationalist histories online, physically attacked Yan Chongnian, a prominent authority on the history of the Qing Dynasty, which was motivated by what Huang perceived as Yan’s whitewashing of the period in his studies of it. This perception also led Huang to liken Yan’s work with those of Holocaust deniers such as David Irving.[23] Such incidents have illustrated how the contentions of the Ming and Qing periods still stir nationalist fervour within China today.

The Hanfu movement’s emergence thus provides the pageantry for the wider Hanist nationalist movement. While the Hanfu craze is not nationalistic in itself, it is a part of China’s growing national consciousness, which has manifested itself in a growing interest in traditional Chinese culture as well as seeing the emergence of a wider Chinese discourse on China’s identity [[24]]. What has also been notable for both these developments is that China’s millennials and netizens rather than the CPC have been the driving forces behind them. In addition, this interest has seen the utilisation of China’s history as a template to predict China’s path in world politics.

Finding China’s ‘Hanist’ Voice

The rise of the Hanfu craze and the associated online discourses have shown the influence that China’s imperial legacies have had upon the perceptions of China’s identity today. In addition, this push has also demonstrated the growing influence of Chinese millennials, who have propelled this interest in China’s traditional Ming clothing and culture. And this generation will also continue to play a greater role in shaping China’s future course.

Alongside this, the discussion in shaping China’s identity has also seen the emergence of a Chinese discourse that has largely grown independently of the CPC. While this demonstrates the agency of Chinese netizens, it shows that their voices will be nationalist rather than liberal in character, as illustrated by the rise of the ‘Hanist’ discourse. In addition, these discourses and the popularity of the Hanfu have also shown the common path taken by newly confident and prosperous societies in that they look towards past glories to tap into an older identity as well as a guide for China’s future. As a result, the trends symbolised by the popularity of the Hanfu are not solely an exercise in nostalgia; they also represent a pursuit of a modernity that is uniquely Chinese in character, which differs from the established Western ideals of modernity.[25] The ‘Hanist’ nationalist path that China’s millenials seek to take promise to have wide-reaching consequences for the world – as well as for China itself.

Dr Tom Harper is a researcher specialising in China’s foreign relations. He received his PhD at the University of Surrey.

[1] Juni Yeung, ‘The Equal Cut: Translating the Culture of Modern Hanfu as Capital’, Translation, Time and History, Spring 2020, 1-20

[2] R. Keith Schoppa, Revolution and Its Past: Identities and Change in Modern Chinese History, Routledge, London, 2019

[3] Zhang Weiwei, China Wave: The Rise of a Civilisational State, World Century Publishing Corporation, Beijing, 2012

[4] Lu, Xing. Rhetoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution: The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture, and Communication, University of South Carolina Press, 2004

[5] Wang Gungwu, ‘China Reconnects: Joining a Deep-Rooted Past to a New World Order’, World Scientific, 2019

[6] Zhang Yan, ‘What is Going on in China? A Cultural Analysis on the Reappearance of Ancient Jili and Hanfu in Present Day China’, Intercultural Communication Studies, 17:1, 2008, 228-34

[7] William Callahan, ‘History, identity, and security: Producing and consuming Nationalism in China’, Critical Asian Studies, 38:2, 2006, 179-208

[8] Liu Mingfu, The China Dream: Great Power Thinking and Strategic Posture in the Post-American Era, Beijing Mediatime Books, New York, 2015

[9] Ying Kit-Chan, ‘Zheng He Remains in Africa: China’s Belt and Road Initiative as an Anti-Imperialist Discourse’, Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies, 37:1, 2019, 57-73

[10] Kenneth M. Swope, The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, 1618-44, Routledge, London, 2013

[11] James Lebold, ‘More than a Category: Han Supremacism on the Chinese Internet’, China Quarterly, 203, 2010, 539-59

[12] Pan Xiaodie, Zhang Haixia and Zhu Yongfei, ‘An Analysis of the Current Situation of the Chinese Clothing Craze in the Context of the Rejuvenation of Chinese Culture’, Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 466, 2020, 504-8

[13] Yeung, 2020

[14] Yeung, 2020

[15] Guo Lan Ying and Jiang Jianxia, The Market Effect of Cultural Transmission in Chinese Costume Dramas: A Case Study of The Untamed, Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 109, 617-21

[16] Pan et al, 2020

[17] Pan et al, 2020

[18] Matthew Chen and Wang Yi, ‘Online Cultural Conservatism and Han Ethnicism in China’, Asian Social Science, 8:7, 2012, 3-10

[19] Li Chuning ‘Children of the Reform and Opening-Up: China’s New Generation and a New Era of Development, Journal of Chinese Sociology, 7:18, 2020, 1-22

[20] Zhang, 2008

[21] Magdalena Grela-Chen, ‘Discovering Roots: The Development of the Hanfu Movement among Chinese Diaspora’ in China and the Chinese in the Modern World: An Interdisciplinary Study, Archaeograph, Krakow, 2020

[22] Lebold, 2010

[23] Lebold, 2010

[24] Chen and Wang, 2012

[25] Yeung, 2020

You must be logged in to post a comment.