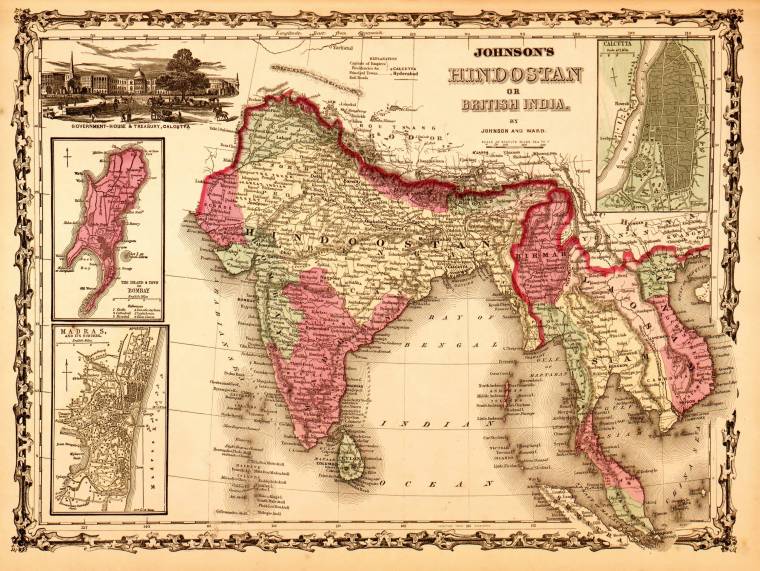

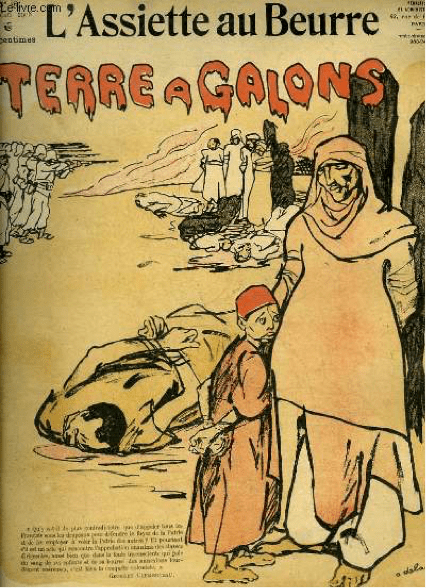

1. Charlie Hebdo is part of a long tradition of dissent in France. Its genealogy can be traced back to the satirical press at the time of the French Revolution. In February 2006, Charlie Hebdo shot to global prominence with its depictions of the prophet Mohammed. But since its launch, the anti-establishment magazine has had plenty of other targets in its sights. Hara Kiri, the publication banned in 1970 for its irreverent take on the death of Charles de Gaulle (and which Charlie Hebdo succeeded) was firmly opposed to French colonialism, particularly during the final stages of the Algerian War of Independence. And much of that French empire was of course in the Muslim world. Jean Cabut (known as ‘Cabu’), cartoonist and shareholder at Charlie Hebdo, a founder of Hara Kiri, and a victim of the 7 January 2015 shootings, linked his own politicization and pacifism to a period of conscription in Algeria in the 1950s. It was also while a conscript in Algeria that Wolinski, another victim of the killings, first came across an advert for Hara Kiri that attracted him to the publication. For more on the history of Charlie Hebdo and its predecessors, see the Exeter Centre for Imperial and Global History.

2. British and French laws on racial and religious discrimination differ in key respects. In Britain, legislation relating to incitement to hatred is applicable to all faiths and creeds and rooted in a multiculturalist tradition. In France, the situation is more complex. Although the offense of blasphemy was abolished during the Revolution, the penal code and press laws relating to freedom of expression still prohibit defamatory communication, or that which incites ethnic or religious discrimination. Legislation passed in France in the 1990s also outlaws declarations that seek to justify or deny crimes against humanity, most notably the Holocaust. In 2007, a French court clearedCharlie Hebdo and its director Philippe Val of defamation charges – filed by the Paris Mosque and the Union of Islamic Organizations of France – relating to the magazine’s re-publication of caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed that had originally appeared in a Danish newspaper. In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack, a number of people have been charged with and convicted for ‘defending terrorism’, under legislation that removes the focus from laws relating to freedom of the press to the criminal code. The tension between such convictions and the commitment to freedom of expression has not passed without comment.

3. Britain and France are still struggling to escape their colonial pasts. This is not only true of how parts of British and French society view immigrants but equally how many immigrants view them. The shanty towns which housed many Algerian immigrants in France after the Second World War were terrible places to live. They were regarded by the French authorities as a danger zones and colonial officials were brought back from North Africa to monitor the conditions affecting Algerian immigrants and the political threat they represented. The association of such precarious housing with marginalization continued until at least the 1970s, and some argue that the housing situation of several migrant communities in France still today reveals continuity between the post-war bidonvilles and the contemporary banlieues. Britain never developed the equivalent of shanty towns, although first generation immigrants from its former colonies struggled to gain access to social housing and often had to rent rooms in dilapidated properties in run-down inner city areas.

4. Despite the recent ramping up of political rhetoric on immigration it is worth reminding ourselves that politicians have not always pandered to public prejudices. Take the classic case in Britain. During the heightened racial tensions of the 1960s, Enoch Powell delivered his famous and inflammatory “Rivers of Blood” speech, a widely publicized attack on the levels of immigration which deliberately cast doubt on the capacity of immigrants to integrate. But at precisely the same time Britain’s first Minister of Immigration, Maurice Foley, was touring the country, warning of the dangers of the growth of extremism. Foley drew attention to the fact that in many parts of Britain immigrants had largely been ignored and abandoned. He called for a common humanity, especially greater respect for immigrant’s own traditions and culture. Similarly in France, two decades later in the 1980s amidst renewed controversy over immigration, the rise of the Front National was challenged by SOS-Racisme, an anti-racist group founded in 1984. Many SOS-Racisme activists have since become prominent if not uncontroversial PS politicians: Harlem Désir, for a time First Secretary, is currently the French Secretary of State for European Affairs; Malek Boutih, former president, is an MP. SOS-Racisme, although not escaping criticism for its Republican and assimilationist stance, has played a key role fighting racial discrimination. It regularly acts as plaintiff in discrimination trials and actively challenging prejudice in both social and legal spheres.

5. The dynamics of the debate about immigration in Britain and France share more in common than we care to admit. Debates regarding French republican identity and British multiculturalism relate to the political will to move beyond a rhetoric of integration to affect a genuine accommodation of migrant communities. In France, the rigidity of a centralized republican model that requires assimilation is countered by an alternative notion of a ‘république métissée’ [hybridized Republic] that maintains core values whilst accepting the necessity of adaptation to twenty-first century cultural shifts and population flows. In Britain, the multi-cultural model is increasingly discredited in the eyes of many because it is said to encourage cultural separation. Repeated calls for “core British values” are offered as an antidote. But when asked to define those values, there is perhaps some irony in the fact that “tolerance” is often top of the list. In Britain and France, some critics of current government policy discern a persistent structural racism with colonial roots.

6. The flashpoints between migrant communities and the rest of British or French society have changed considerably over the last half century. Inter-racial relationships and mixed-marriages were once of far greater concern. Today the markers of integration (or its perceived absence) are more likely to be Islamic customs and practices (codes of dress, treatment of women, religious imagery), attitudes to which may differ among Muslims as well as between the Muslim and non-Muslim parts of the population. In France, intermarriage was met with hostility in the earlier part of the twentieth century, especially after the First World War. Attitudes have since changed. The 1999 census suggests that 38% and 34% of male and female married immigrants, respectively, are intermarried (including around 30% of those of North African heritage). A recent study has indicated that despite perceptions of its active multiculturalism, Britain may in fact have less immigrant assimilation through marriage than is sometimes suggested. Britain has a lower number of mixed marriages than France: it was reported that 8.8% of British marriages include one foreign-born partner compared with 11.8% in France.

7. There are a lot of myths about immigrants not speaking the language of their host country that recent data dispels. The 2011 census in England and Wales has allowed detailed mapping of linguistic diversity – in particular the super-diversity associated with many urban wards. The census revealed that, of the 8% (4.2 million) of residents aged three years and above with a main language other than English, 79% (3.3 million) could speak English very well or well; only 0.3% of the population (138,000) cannot speak English, with the majority of these likely to be recent arrivals. Comparable data for France is not available as national statistics are not permitted to reflect markers of ethnic diversity. The 1999 census nevertheless posed questions to a sample of 380,000 adult respondents about their family situation, including one relating to the languages in which their parents spoke to them before the age of five. The results suggested that 940,000 people consider Arabic to be their mother tongue, but these figures do not capture actual language practice and only reflect the activity of those born before 1981. In both national contexts, it is clear that acquisition of English or French remains a key element of social cohesion, although, for differing reasons, multilingualism is still seen as more of an impediment than an asset.

Jeremy Black

Jeremy Black

You must be logged in to post a comment.