Marc-William Palen

History Department, University of Exeter

Follow on Twitter @MWPalen

According to a longstanding international relations theory, the global economic order is at its most orderly when there’s at least one hegemonic free-trade champion.

As per this theory, Britain took this role upon itself in the mid-nineteenth century, ushering in a brief transatlantic flirtation with trade liberalization and relative hemispheric peace.

The United States was the first major nation to turn against this mid-nineteenth century free-trade epoch. From the Civil War to the Great Depression, the United States instead embarked upon nearly a century of Republican-style economic nationalism, which I’ve explored in my own work.

But this began to change following the Second World War when the United States assumed the mantle of free-trade hegemon. Promising prosperity, profits, and peace to the world, it sought to foster international trade liberalization through supranational initiatives like the International Monetary Fund (1944) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947), the latter of which morphed into the World Trade Organization in 1995.

Well, the times they are a-changing again.

Trump’s fast-developing protectionist and ultra-nationalist “America First” program has signalled that the United States is abdicating its role as free-trade leader. As the New York Times noted earlier this month:

President Trump’s advisers and allies are pushing an ambitious idea: Remake American trade. They are considering sweeping aside decades of policy and rethinking how the United States looks at trade with every country. Essentially, after years of criticizing China and much of Europe for the way they handle imports and exports, these officials want to copy them. This approach could result in higher barriers to imports that would end America’s decades-long status as the world’s most open large economy.

The Trump regime’s protectionist trade vision is fast becoming reality.

So what does this mean for the future of the global economic order?

And have we seen all of this before?

To kick things off, Trump, in his first big act in office, withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a massive Asia-Pacific trade deal that the Obama administration had long championed.

Soon after this, Trump took aim at the WTO.

Now the breaking news this past weekend has centred around the outcome of the year’s first G20 meeting, made up of the finance ministers of the world’s 20 biggest economies.

According to the BBC

It started so well. With the sun shining in the German spa town of Baden-Baden, the first annual meeting of the G20 got under way with a reassurance from the US Treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin that the White House was not interested in instigating international trade wars. The combined efforts of Germany, and nascent free-trade champions China, it was thought, would temper some of Washington’s threats of imposing punishing border tariffs and renegotiating long-standing trade agreements.

But, thanks to the Trump administration, the end result was quite different from previous G20 meetings.

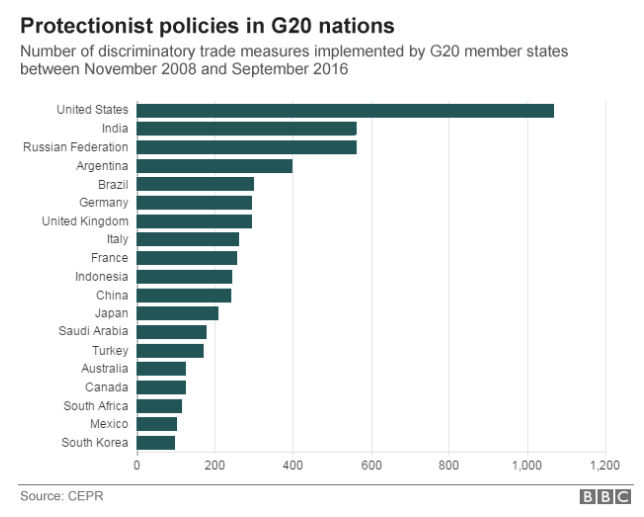

Last year, the group of the world’s 20 largest economies vowed to “resist all forms of protectionism”. But since then, President Donald Trump has taken office, and is aggressively pursuing an “America First” policy.

These developments brought to mind an interview I did last April for my book, The “Conspiracy” of Free Trade: The Anglo-American Struggle over Empire and Economic Globalisation (CUP, 2016). At that time, I suggested that history was not a crystal ball:

I’m not at all surprised to see free trade coming under fire in a presidential election year; it’s to be expected. Nor am I surprised to see that the presidential debates over economic globalization are largely devoid of historical context. But what does surprise me is that the issue has become such a crucial element within all of the campaigns, cutting across party lines.

I think what makes this even more remarkable is that for at least some of the candidates – Bernie and the Donald — their critiques of free trade are more than populist posturing during an election year. In contrast to Hilary Clinton or the other Republican candidates, I think that Sanders and Trump mean what they say when they call for a new trade regime. If either one were elected president, I believe they would seriously attempt to change the course of US trade policy. Regardless of where one stands on this issue, this is important because it holds forth the very real possibility of the transformation of American – and thus global – economic integration in the very near future. . . . History is no crystal ball, but America’s protectionist past ought to provide a useful glimpse into what might occur under a Trump presidency.

But maybe I was wrong. Maybe history is a crystal ball. Maybe “nascent free-trade champions” like Germany or China will take up the position now vacant, much like the United States did in the 1940s.

Or maybe they won’t. If that happens – and if history is in fact a crystal ball – then the late 19th century and the 1930s offer a vivid historical vision of what lies in store for the global economic order – one that promises a global turn to protectionism, trade wars, authoritarianism, and ultra-nationalism.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.