Entrevista a los organizadores de ‘Los diálogos del aguacate’Parte 1

23 de junio de 2020

Por, Centro de estudios latinoamericanos de Exeter (EXCELAS) Esta es una continuación a los diálogos iniciados por el Grupo de Trabajo Decolonial, con el fin de articular e integrar las iniciativas en curso relacionadas con el tema. |

Interview with the organizers of ‘The Avocado Dialogues’Part 1

June 23, 2020

By, Exeter Centre for Latin American Studies (EXCELAS) This is a continuation of the dialogues provoked by the Decolonial Working Group to integrate and articulate with on-going initiatives. |

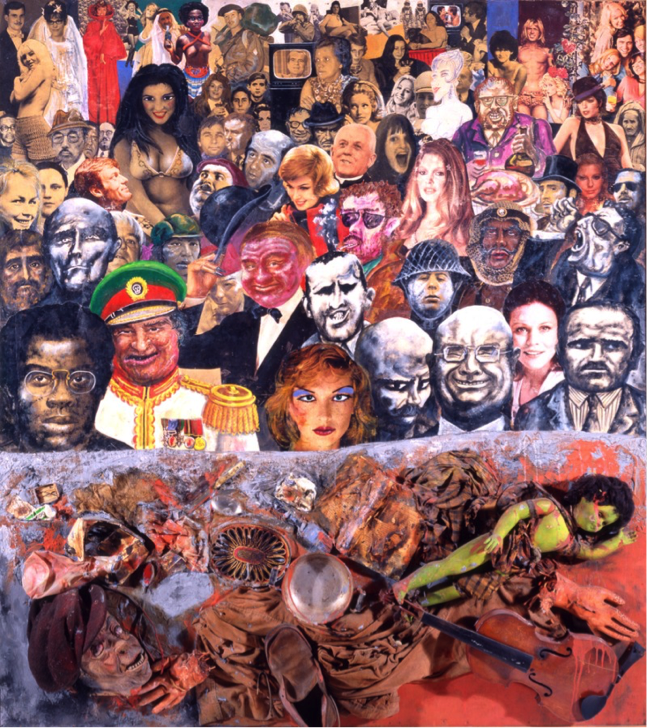

Photo: Antonio Berni, The Silent Majority, 1972

| Silvia Espelt Bombín: ¿Por qué decidisteis organizar los Avocado Dialogues?

|

Silvia Espelt Bombín: Why did you decide to organize the Avocado Dialogues?

|

| Adrián Oyaneder Rodríguez: Esta idea nace de una motivación mía por hacer eventos de este tipo, por poner a Exeter en el mapa dentro de las Humanidades y Ciencias sociales y porque, en el fondo, EXCELAS me impulsó a dar a conocer localmente los estudios latinoamericanos. Cuando el año pasado hicimos el SAAME, el congreso de arqueología latinoamericana, nos dimos cuenta de que con el formato clásico se constriñe el intercambio de ideas porque es jerárquico, por eso pensamos en desarrollar un taller que fuera mucho más participativo y horizontal. Además, consideré que era importante cobrar un carácter interdisciplinario y es por esto que contacté a Diana ya que ella, en su investigación, trabaja distintos puntos de vista a nivel de disciplina.

|

Adrián Oyaneder Rodríguez: This idea comes after my motivation to organise events of this type, to put Exeter on the map within the Humanities and Social Sciences, and because EXCELAS prompted me to make Latin American studies known locally. During the first SAAME (South American Archaeology Meeting at Exeter) last year, we the organisers realised that conference format constrains the exchange of ideas because of its hierarchical nature. Thus, we thought of developing a workshop that would be more participatory and horizontal. Besides, I considered that interdisciplinarity was key, and for that reason I contacted Diana since she in her research combines different disciplines.

|

| Diana Valencia Duarte: Gracias a mi PhD empecé a conocer otras metodologías, pues vengo de las ciencias naturales. Fue mi trabajo de campo el que cambió completamente mi perspectiva. Aunque hice un trabajo exploratorio de archivo ortodoxo, comprendí que es muy diferente a ver la historia desde el territorio. En los entornos participativos locales en Colombia descubrí un nuevo mundo de posibilidades: la memoria medioambiental, los discursos decoloniales, los diálogos de saberes. Cuando hice mis entrevistas algunos campesinos me dijeron “nosotros hemos hecho investigación y de hecho tenemos estos libros y te los vamos a regalar”. Así conocí uno de los trabajos que estudiaremos en el taller. De vuelta en UK participé en un panel sobre cómo hacer historia incluyendo a los actores que han estado excluidos, y vi que teníamos un vacío de entrenamiento sobre metodologías participativas. Cuando llegó Adrián con la iniciativa, trabajamos la idea y nacieron los diálogos del aguacate, asimilando el diálogo de los saberes al aguacate como un producto originario de Latinoamérica pero que hoy día se disfruta globalmente. | Diana Valencia Duarte: It is during my PhD in the History department that I became familiar with other methodologies, given that my background is in the natural sciences. What completely changed my perspective was my fieldwork. Although I had previously done orthodox archival work, my work in the field allowed me to see and understand things differently. I discovered a new world of possibilities in local participatory settings in Colombia: environmental memory, decolonial discourses, dialogues of knowledge. When I did my interviews, some peasants told me “we have done research and in fact we have these books.” And they presented me with their books. This is how I came across one of the cases that we will discuss in the workshop. Once in the UK I participated in a panel on how to write history including neglected actors. Then my own reflections made me realise that we had a training gap in participatory methodologies. When Adrián approached me, we worked on the idea and ‘The Avocado Dialogues’ were born. The name comes from assimilating the dialogue of knowledge with avocado, a product originally from Latin America and today appreciated globally.

|

| Silvia: Adrián, dado que también existe una arqueología participativa, ¿sería ese también el contexto en el que nace tu idea de organizar este taller?

|

Silvia: Adrián, given that there is also a participatory method in archaeology, did it have an impact in your idea to organise this workshop?

|

| Adrián: La idea también deviene de mi directora de tesis, Marisa Lazzari, que practica una arqueología híbrida aplicando técnicas de las ciencias duras e integrando el trabajo participativo con comunidades. Yo estudio el norte de Chile en la vertiente occidental de los Andes y Marisa trabaja el lado oriental andino. En ambos lugares hay comunidades indígenas y comunidades locales que han vivido procesos de auto reconocimiento indígena. Estas comunidades tienen una larga trayectoria de problemas con los arqueólogos porque se nos ve como como entes extractivistas del conocimiento. En la experiencia chilena hay muy buenos ejemplos de desarrollo y de participación con las comunidades en los Andes, pero también se han visto casos totalmente contrarios donde no se incluye a las comunidades. Esto ha generado graves conflictos que incluso han llegado a la corte suprema, donde se ha dictaminado en algunos casos que los arqueólogos no pueden desarrollar más excavaciones (todo esto gracias al rol legislativo del convenio 169 de la OIT). Hay un fenómeno bien interesante que se está desarrollando en la arqueología en general.

|

Adrián: The idea also comes from my PhD supervisor, Marisa Lazzari, who does hybrid archaeology by performing a combination of techniques from the hard sciences and from participatory work with communities. I study the north of Chile on the western side of the Andes and Marisa works on the eastern side. In both places there are indigenous communities and local communities that have experienced processes of indigenous self-recognition. These communities have a long history of problems with archaeologists because we are seen as knowledge extractors. From the Chilean experience there are good examples of development and participation with communities in the Andes, but there are also controversial cases where communities are not included. This has generated serious conflicts that have reached the Supreme Court of Justice, where it has been ruled in some cases that archaeologists cannot carry out any more excavations (all this due to the legislative role of ILO Convention 169). There is a fascinating phenomenon that is developing in archaeology in general.

|

| Silvia: ¿A qué tipo de retos os enfrentasteis organizando los Avocado Dialogues con un enfoque participativo?

|

Silvia: What kind of challenges did you face organizing the Avocado Dialogues with a participatory approach?

|

| Adrián: El primer reto fue conseguir el financiamiento para invitar a Exeter a gente de Reino Unido, Latinoamérica y otros lugares. Para ello solicitamos fondos de la Universidad (el Research Led Initiative y el Activity Award del College of Humanities). Con la pandemia, el principal desafío fue pasar de un evento organizado físicamente en Exeter a hacerlo plenamente digital. Es Diana quién ha liderado esta transición.

|

Adrián: The first challenge was obtaining the funding to invite people from the UK, Latin America and elsewhere to Exeter. We applied and obtained funds from the University’s RLI funding and the College of Humanities Activity Award. With the pandemic, the main challenge was to transition from a physically organised event in Exeter to a fully digital one. It is Diana who has led this change.

|

| Diana: La transición la facilita que el evento ya era un evento híbrido con una parte virtual, la participación de la Comunidad de investigadores afro-campesinos de la alta montaña de Los Montes de María. Una barrera intrínseca es que las comunidades no tienen los mismos recursos que tiene una Universidad, hay que suministrar todo el apoyo para transporte rural remoto, alquiler de computador e internet, recarga de celular, etcétera. Adicionalmente, está la barrera del idioma. De manera que, aunque fue un reto, el pasar todo a modo virtual nos liberó recursos para tener otras cosas, por ejemplo, traductores profesionales para integrar completamente a los afro-campesinos.

|

Diana: The transition was eased by the fact that the workshop was already a hybrid event. It already had a virtual part: the participation of the community of Afro-peasant researchers from the high mountains of Los Montes de María in Colombia. An intrinsic barrier to their participation is that the communities do not have the same resources that a University has, and it is necessary to provide all the support for remote rural transportation, computer and internet rental, cell phone top-up, etc. Additionally, there is the language barrier. So, although it was a challenge, turning everything into virtual mode freed up resources to have other things, for example, professional translators to fully integrate Afro-peasants. |

| Silvia: ¿Podríais hablar un poco más sobre la cuestión del idioma y de la preeminencia de unas lenguas sobre otras?

|

Silvia: Could you talk a little more about the question of language and the pre-eminence of some languages over others?

|

| Diana: Básicamente porque estamos hablando de comunidades campesinas, que no han tenido nunca la necesidad de usar el inglés porque su investigación no tiene el fin de alimentar la academia. Ellos aprecian el interés académico pero el trabajo que ellos desarrollaron fue con el fin de reconciliar y reparar unos hechos de violencia como víctimas del conflicto a las cuáles el Estado debe reparación integral. A través de esta metodología de investigación y la participación de todos los miembros de la comunidad, se generó reconciliación entre ellos. Realmente la traducción no es tanto para ellos – aunque facilita esa inclusividad – si no para nosotros, que como investigadores en formación podamos aprender de ellos.

|

Diana: We are talking about peasant communities, which have never had the need to use English because their research is not intended to feed academia. They appreciate the academic interest but the work they carried out was to reconcile and repair acts of violence. They are victims of the conflict and the Colombian State owes them comprehensive reparation. It was only through this research methodology, which involves the participation of all members of the community, that they achieved collective reconciliation. The translation and simultaneous interpretation of the event is not so much for them – although it facilitates inclusiveness – but for us, as researchers in training who want to learn from them.

|

| Adrián: En Latinoamérica siempre está la discusión del por qué la preponderancia de publicar y comunicar nuestras investigaciones en inglés, sobre todo ahora que las publicaciones de mayor impacto justamente están en inglés y por lo tanto se limita el acceso a investigadores locales que ciertamente no tienen por qué hablar inglés. Esta preponderancia idiomática es colonialista y yo creo no tiene por qué existir. Pero también nos vimos enfrentados a la situación de que, al estar en Exeter y sustentar el evento con fondos de la Universidad, debimos mantener el inglés como idioma principal. Ahora, de igual forma es interesante el hecho de que el segundo congreso SAAME, decidió pasar al español una vez que se pasaron todas las conferencias a un formato online. Esta preferencia idiomática abre muchas más puertas a la discusión el dejarlo en español, ni siquiera español, pero latinoamericano.

|

Adrián: In Latin America there is always the discussion of why the preponderance of publishing and communicating our research in English, especially now when publications of greatest impact are precisely in English. Therefore the access to them is not easy for South American researchers who certainly do not have to speak English. This linguistic preponderance is colonialist and I do not think it has to exist. Even though this critique, we faced the dilemma of doing the workshop in English as we are in Exeter and the funds are from the University. Now, equally appealing is the fact that the second SAAME conference decided to move to Spanish once most of the events transitioned to an online way. This language preference opens many more doors for discussion by leaving it in Spanish, not even Spanish, but Latin American.

|

| Silvia: ¿Cuál es vuestro rol en el taller?

|

Silvia: What is your role in the workshop?

|

| Adrián: La idea no es figurar a nivel académico, sino que siguiendo nuestras líneas de investigación juntar nuestra gente para sacar algo interesante y poner a la palestra/luz en la academia británica y particularmente inglesa este tipo de discusiones respecto a la decolonialidad y la investigación participativa. En ese sentido por ejemplo en nuestra página web aparecemos solo al final a manera de contacto, pero no nos colocamos como protagonistas, estamos tras bambalinas.

|

Adrián: Our objective is not to be visible at an academic level, but to follow our line of research and to bring people together to create something stimulating and to make known in British and particularly English academia this kind of discussion regarding decoloniality and participatory research. In that sense, for example, on our web page we appear in the section contact us, but we do not place ourselves as protagonists, we are behind the scenes. |

You must be logged in to post a comment.